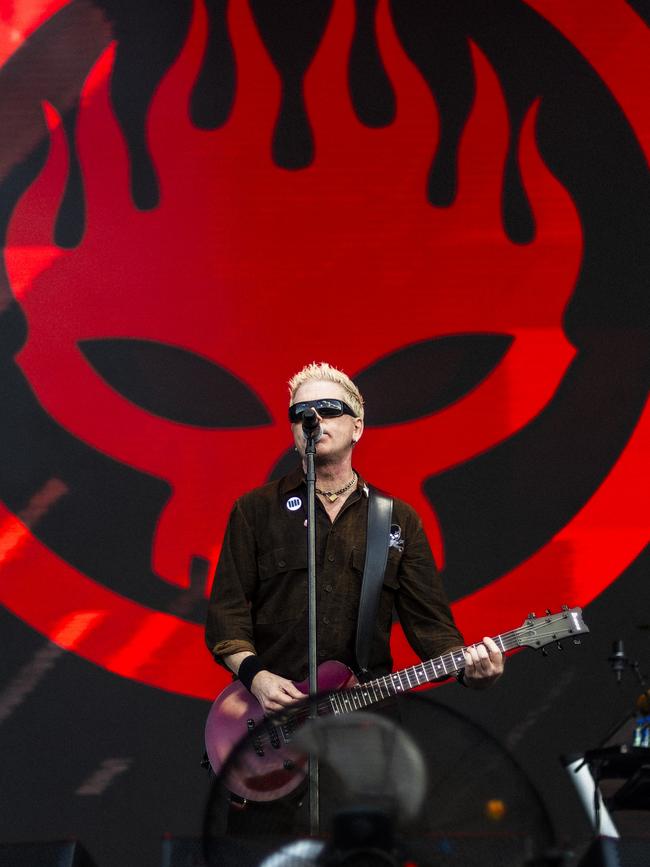

Dexter Holland of The Offspring on mad Brazilian fans, grief and hot sauce

In an extended Q+A, Dexter Holland — frontman of veteran US punk rock band The Offspring — speaks about touring with kids, the upsides of ageing, mad Brazilian fans, grief and hot sauce.

Dexter Holland, 59, is the frontman of the chart-topping US punk rock band The Offspring. In an extended confessional Q+A, he speaks about touring with kids, the upsides of ageing, mad Brazilian fans, grief and hot sauce.

How has your relationship with performing live changed across the years?

Dexter: It’s always been the core of what we do, right? What’s changed is that the crowds have gotten bigger, and that’s a good thing – but that creates a different kind of challenge, in that you’re trying to figure out how to connect with that bigger crowd. We grew up in small clubs with a couple hundred people, if we were lucky, and it was very easy for it to feel like you’re playing in someone’s living room … we’ve played living rooms, actually! [laughs] You know how to do that thing; it’s almost conversational, and it’s not like you’re posing or doing something grand, or have fireworks going on behind you. You have to be able to talk to the crowd and entertain them. Now, all of a sudden, we’re playing these places where those same kids are 200 yards back [from the stage]. How do you connect with that person? It’s a different approach, and I feel like I’m still trying to figure out how to keep it conversational. I guess that’s part of why it’s still fun being in a band; there’s always something new to figure out. It’s a new puzzle: every show is different, and every tour is different.

It’s now 40 years into The Offspring’s career, and more than 30 years since the release of Smash, your breakthrough album [in 1994]. What does it feel like to continue to fill large venues around the world, including here in Australia?

What’s actually crazy in the last couple years – post-Covid, I guess – is that it’s gotten bigger. A lot of bands I’ve seen after 20 years, it kind of diverges: either they go up, like KISS or something, or they take a nose dive [laughs] I always wanted to be in the former group, right? How do you do that? I don’t know, but it’s almost like we’ve caught on all of a sudden, and we’re having the biggest shows we’ve ever done. This is gonna be our biggest tour of Australia; our biggest venues. We’re just super pumped. Things are better than ever.

Where does writing and releasing new music fit into that for you?

It’s super important. It’s almost like two sides of the band; the yin and the yang. The live performance is very fun because there’s immediate reaction and connection: you sing the song and they sing it back to you, and there’s no feeling like it. It’s a great high, for sure. But the other side of that is getting into the studio and creating something from nothing. You’re putting something down, and all of a sudden you’re finished with this song, and it’s like a remote control car: you can play the song, and it just plays all by itself, you know? [laughs] There’s something really cool about that. Supercharged is our 11th album, and it’s harder and harder to make a new song stick, because people like what they like, and that’s always a new challenge. But I feel like, if I wasn’t doing the studio, and we just went out and played our songs night after night – that would feel like punching a clock. That would feel like, “I’m playing the oldies; I might as well just be at a job”. I don’t think we’ll ever give up the recording part.

Supercharged was released last year, and what caught my ear on first listen was Come to Brazil. What’s the story behind that song?

It’s funny: if I talk to a social media guy, they laugh. If I talk to my mother, she’s like, “I don’t get it. What does that mean?”. [laughs] Maybe it’s a little bit generational. But we’ve always had, on all our social media platforms, when we post about a new record, they’ll [reply], “We’re so stoked! Come to Brazil!”. But it’s turned into this joke where it doesn’t matter what you say anymore. It could be like, “Happy birthday [to guitarist] Noodles!”, and they’ll write, “Come to Brazil!”. It’s touching, in a way, and flattering, and I know we’re not the only band that has this; most bands have it now, I think. But it’s just became so farcical and so funny – and as I’m writing it, I’m like, “I can’t believe no one’s done a song called Come to Brazil yet!”. [laughs]

That is the one time when I wrote a song where it just started with the idea, and the phrase. How do we build the perfect song for Brazil around it? And the idea is that, well, the verses would be kind of speed metal [style], and the choruses would be a soccer stadium chant, and then the end would be Olé, Olé, Olé. [laughs] It was constructed as a thought experiment, and we haven’t gone to Brazil since we’ve released the song, so it remains to be seen whether it worked. But I’m hopeful.

What’s your relationship with the electric guitar today?

Noodles [aka Kevin John Wasserman, who joined the band in 1985] is the kind of guy that, if you walk into a room, he’s going to be on the guitar. That’s how he got his nickname, because he wouldn’t stop noodling on the guitar; it’s just an extension of him. I love playing guitar, too, and I’ve grown to love it more over the years, but Noodles thinks I see guitar as a means to an end. [laughs] That sounds so clinical, right? I don’t want to agree with that. It is a great tool, of course, to write songs with, and maybe that was part of the motive when I first started.

You’ve had that thing in your hands for more than 40 years. What’s your relationship with mastery in relation to playing guitar?

No one’s ever accused us of being good musicians, for sure. [laughs] We’ve definitely gotten better at it over the years. Once, Bob [Rock, producer, with whom the band has worked since 2008] said, “You guys aren’t virtuosos, but I would call you journeymen – and I mean that in a good way”. We’re not accomplished, but we’re doing it in this way to get the job done. And sometimes there can be a charm in that; the Ramones weren’t excellent musicians, but the way they played their stuff enhanced the song. I took the “journeyman” comment as a compliment. I don’t consider myself a good singer, but there’s one thing that I can do: I can sing kind of high, and kind of hard. It’s the same on guitar: I can’t play Eddie Van Halen’s Eruption, or anything like that – but I can hold down a good “chug”. [laughs]

The band’s 1997 single, Gone Away, was a stylistic left-turn that remains a fan favourite today. What inspired that song, as a ballad about grief?

It felt like it was very out-of-the-box for us, and that made it a little bit scary to put that out. That was also on Ixnay [on the Hombre], which was the follow-up to Smash. I knew that we couldn’t just do Smash Part Two; we had to expand the circle of what we were musically, in order to be able to continue. So it was an important part of that journey, to put a song like that on the record.

At the time, it was not a massive hit; it did fine. But what has really struck me about that song is how it has grown over the years, and it’s because it connects on this very fundamental emotional level, I guess because everyone can relate to the loss of someone who’s close to them. I should have realised that this is about as close to personal as you can get with somebody – but I didn’t at the time. That’s been really cool and really meaningful, and it’s a big moment in the set.

What’s your relationship with the act of repetition?

Do we get sick of our songs? Maybe after the first hundred times you play it, you’re like, “Oh my gosh, kind of …”. But after 500 times, it becomes part of you, every night. It’s not a matter of being sick of it, or not sick of it – it’s just part of who you are. Even beyond that, because a song like [1994 single] Come Out and Play goes over so well every night, it’s a fun part of the set. It’s something I look forward to; it’s not a drag at all to play those songs.

Do you have a philosophy on money?

I grew up in a very middle-class family [in Orange County, California]; we definitely weren’t poor, by any means. My parents could take us to the lake once a year, but we did not have extra money for anything. I knew that I was going to have to work for whatever it was. As we became involved in the punk scene, we were doing a lot of shows up in Berkeley, which was very hippie, and there was a very “anti” attitude towards money. I saw what they were saying, about the evils of capitalism, greed and all that kind of stuff. But I also saw – especially the older you get – that if you have money, you’re able to help people. That’s always been a really big motivator; being able to help my mother, for example, who’s living on a fixed income. I don’t ever feel ashamed of making the money, because I see what I can do to help the loved ones around me.

What lifts your mood if you ever find yourself feeling sad?

Listen to Joe Cocker’s Feelin’ Alright [laughs] You can’t stay sad if you listen to that song; it’s just too good. Besides the vibe of the music, his voice in that song is so beautifully ugly; it’s incredible. Even more than that, there’s a freedom in it, man, the way he just goes for it. He doesn’t care how rough around the edges it is; he’s going to that place, and it’s really, really cool.

I love that a song is your cure for sadness, or at least a temporary balm. That’s the power of music.

It is, and that’s something that I struggle with sometimes, as I go into this [career] further and further. When I see people excited at our show, I’m like, “Oh, god – it’s just us!”. I can’t see us the way they see us, right? But I can tell you how excited I am about this Joe Cocker song, and why it means so much, and what his voice does and stuff. I recognise that music has a lot of power to change how you feel, and that’s an amazing thing.

The Offspring sometimes offers “meet and greet” tickets for fans willing to pay a little extra. What are those experiences like from your perspective?

It’s kind of like a parade, and it can feel very robotic after a while: “Here’s a person, shake their hand. OK, everyone look at the camera. Great, thanks, see you later ...” It almost feels phony in a way; there’s no real interaction. But I guess there’s an understood barter: they want to meet you, and they want the souvenir, or the trophy. “Here’s my picture”, right? That’s changed over the years, because I used to sign a lot of autographs; that was all you could do before camera phones. I would like to structure a meet-and-greet so that it’s a little bit more like we walk into a room and chat for a few minutes. We tried those, and that gets tough as well, because then some somebody will monopolise you, and you can’t get through the people. That’s another challenge that we haven’t quite figured out.

What’s the best thing about having your own hot sauce company [Gringo Bandito]?

Well, it’s a good ice-breaker, and a good calling card, because it’s kind of funny. When people say, “Hey, you have a hot sauce!”, it makes them smile. If I had to have a product, I wouldn’t want to have a yoghurt, for example. Some people don’t even like the band, but they like the hot sauce. You’ve got two chances to like me: it’s either the band or the hot sauce, and the hot sauce almost always wins. [laughs]

What’s the hardest thing about juggling parenting and a career in the creative arts?

I think it’s knowing where to set the boundary. I have a daughter who’s all grown up now [Lex Land, a fellow musician], and when she was really young, my mentality was, “Tour is no place for kids”. I felt very strongly about that, because even though I’m not into drugs or whatever, you’re around that every day. It’s drugs, alcohol and staying up late, and the irregularity of life, and the instability of being on the move all the time. I felt like that for a long time; now I have two little ones [aged nine and five], and my wife’s mentality is, “We go where you go, because otherwise, what’s the point?”. So it’s really changed, and this could also be because I’m decades older now. [laughs] Our world has changed: it used be a lot of shots and cigarette smoke backstage. Now, it’s little kids: we all have young kids running around and screaming, and eating all the chocolate.

I said it’s a matter of setting boundaries, and you’re always trying to figure out where that right boundary is. Is it better to let them be on the road, and they’re going to miss school, be up all night and jet-lagged – or is it better to not have them around? How do you balance being strict enough to give them the moral compass you want them to have, and yet flexible enough to live life the way you have to?

What was the best deal you ever made?

I guess the best deal was the one that I didn’t make. We had recorded Smash on an indie label [Epitaph Records], and it was about to come out, and of course, no one knew what that record was going to do; we were a very small band. But the label liked it so much that they wanted to buy my publishing. They said, “Tell you what – I’ll give you some money for your publishing, and you could use it to write more songs”. At that point, I was a grad student, so I had a stipend of like $1000 a month. I basically had to live at home in order just to go to school – so anything would have been a lot of money. I forget what the number was; say it was $75,000 or something like that.

I sat down to lunch with them, they presented the offer, and I go, “You know what? That sounds really good, and I’m very flattered – but I’ve got a good feeling about this record. I think I’m gonna say no for now”. [laughs] It even surprises me looking back on it: “Dude, are you crazy? That would have been a lot of money!” I guess maybe I had a guardian angel looking out for me, and I had the sense to not make that deal at the time.

Smash went on to sell more than 11 million copies worldwide, and it remains the highest-selling indie album of all time. What was the upside of not taking the $75,000 or so that was offered? Are we talking millions?

Yeah, for sure. And it’s not that they were being predatory. I don’t mean to paint them in that light; they were just trying to make a deal.

Smart move. Life at 59 is …

A race against the clock, man. [laughs] I’m saying that kind of facetiously, but you can’t help but do the math sometimes: “OK, well, if I want to do this big Australian tour, I don’t want to wait 10 years; at some point it’s just not going to feel right anymore.” There’s all these things I want to do. I do triathlons, and I might do an Ironman [long-distance race, time-limited to 17 hours], and I’m going, “Well, f..k – I’m gonna be 60 next year; if I’m gonna do it, this has to happen ...”. In a way, age becomes a great motivator. It’s not necessarily a bad thing, but you do feel this internal pressure in a way that maybe you hadn’t before, to make sure that you fit in all the things you want to in life. I guess that’s a good thing.

Carpe diem, right?

For sure. There’s a lot of that in punk music. You can classify punk a lot of different ways: the Sex Pistols were nihilists, the Dead Kennedys were political … At least for us, there’s this real spirit of independence: you need to forge and find your own way. “F..k authority” fits into that in a certain way, in that you have to define what’s right, and question what’s being told to you, instead of just accepting what people say you have to do. But “carpe diem” totally fits into that. It’s punk.

The Offspring’s six-date tour with Simple Plan starts in Adelaide on May 4 and ends in Brisbane on May 14 and 15.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout