Brady Corbet: ‘Companies financing movies are risk-averse’

In the increasingly tough movie industry, the director has taken a gamble with the 3½-hour architectural drama The Brutalist, but it may just pay off.

Chances are, you haven’t heard of filmmaker Brady Corbet. But come March, don’t be surprised if he strolls onto stage to collect the Academy Award for Best Picture.

The Brutalist, Corbet’s 3½-hour post-war architectural drama, was the toast of film festivals last year.

At Venice, where it premiered in September, it received a 13-minute standing ovation — eclipsed only by Pedro Almodovar’s English-language debut, The Room Next Door (but who doesn’t feel immense goodwill towards Almodovar?). Corbet walked away with the Silver Lion for Best Director.

The seven-years-in-the-making film could easily have been one of those art house darlings that burns bright for a moment before settling into the muted oblivion reserved for the critically adored but little-seen.

Corbet himself acknowledged this precarious fate during his Golden Globes acceptance speech in January. “No one was asking for a 3½-hour film about a mid-century designer on 70mm,” he quipped. And yet, there he was, cradling the trophy for Best Drama. If there was ever proof of the film’s improbable crossover to mainstream appeal, this was surely it.

The Brutalist chronicles 30 years in the life of Laszlo Toth (Adrien Brody), a distinguished Hungarian-Jewish architect and Buchenwald survivor. He arrives in post-war America alone, impoverished and anonymous, ready to start a new life while awaiting the arrival of his wife, Erzsebet (Felicity Jones), who is trapped in Hungary with their selectively mute niece.

After settling in Pennsylvania, his talents are recognised by millionaire industrialist Harrison Lee Van Buren (Guy Pearce), who commissions Toth’s first American building — a community centre that comes to be known as The Institute.

Van Buren, suave yet predatory, is portrayed with chilling precision by Pearce, in a career-best performance that earned him his first Oscar nomination. He is a reptile in the suit of a gentleman. When he first meets Toth (who has been hired by his snot-nose son, played by Joe Alwyn, to remodel the library) he initially perceives him as an intruder, a dishevelled immigrant, before discovering the architect’s celebrated past. From there, he invites him into his inner circle, but his motives are clear: Van Buren doesn’t want to elevate Toth, he wants to possess him — a pawn in his own quest for intellectual vanity. He seeks to subjugate, not uplift.

“I knew I wanted someone still very attractive in the role,” Corbet says of Van Buren. “There’s, of course, a version of the American industrialist that’s geriatric. But I wanted there to be this virility. I wanted to feel that these two men were, in some ways, at least physically evenly matched.” He knew Pearce was the man for the job after seeing him in Mildred Pierce, Todd Haynes’s television adaptation of the James M. Cain novel.

“It really stuck with me. It’s just such a fantastic performance,” Corbet says. “He was doing a different variation of the mid-century dialect in that project, and that’s really difficult to pull off. He just nailed it. For some reason, Australians, in general, are very good at accents. Much, much better than Americans. We can’t figure it out; it must be something in the water,” Corbet laughs.

The Brutalist, at its heart, is a story of artistic ambition tested by the cold machinery of American capitalism. It’s a sprawling, achingly romantic portrait of a man driven to create something monumental, only to see his vision diminished by the brutality of his adopted country.

For Corbet, it’s personal. “This was the only way I could make a movie about making a movie,” he laughs wearily. “I joke about it all the time, but unfortunately, the documentary about making movies wouldn’t look like Burden of Dreams or Heart of Darkness. It’d be much more administrative. It’s torturous, but it’s more like working at the DMV (Department of Motor Vehicles).”

Corbet says that writing The Brutalist with his wife, Norwegian-born filmmaker Mona Fastvold, was “something like an exorcism” — a way to channel their frustration and rage about the filmmaking process. “It’s difficult for absolutely everybody. I think it’s genuinely gotten harder, not easier, in the last decade.”

He should know — he’s spent his life on film sets. The 36-year-old Pennsylvania native, raised by a single mother, began his career as a child actor. Then he became a millennial art house star, working with cinema masters: Michael Haneke (Funny Games), Gregg Araki (Mysterious Skin), Lars von Trier (Melancholia), Olivier Assayas (Clouds of Sils Maria). He also starred in Catherine Hardwicke’s gritty cult classic Thirteen, a film that still inspires TikTok fancams thirsting over his brooding teen heart-throb days.

He quit acting a decade ago to step behind the camera, directing two independent features: 2015’s The Childhood of a Leader, a fictional account of a fascist leader’s childhood, and 2018’s Vox Lux, a Natalie Portman-led critique of prefab pop stardom. Both films, co-written with Fastvold, cemented his reputation as a promising auteur with an uncompromising vision. Financially, though, they were disasters. Vox Lux cost $US11m ($17m) to produce and brought in just $US1.5m, while The Childhood of a Leader, made for $US3m, grossed less than $US250,000.

“Most companies financing movies nowadays are especially risk-averse,” Corbet says. “It’s easy to understand why — there are not enough people going to theatres. But it becomes a vicious cycle. When people make less interesting, original work, of course, audiences don’t show up. It requires a huge leap of faith, not just from financiers but from everyone involved. To make movies like this, it’s a huge investment of time for very little financial return.”

The Brutalist, considering its runtime and star power, was made on a modest budget of $US10m. “We had to get clever in how we moved sand around the box to absorb costs because the film wasn’t made for much money,” Corbet explains.

It is also the first film shot entirely on the long-dormant VistaVision format — a high-resolution 35mm — since Marlon Brando’s 1961 directorial debut, One-Eyed Jacks. The film print arrived in Venice in 26 separate canisters, weighing a total of 136kg. There’s a viral video showing the festival projectionist flexing in triumph after threading the final reel.

The projectionist of #TheBrutalist at the end of 4 hours of 70mm projection #venicefilmfestivalpic.twitter.com/FhOa5JXRUC

— jason_lester (@Jason_Lester) August 31, 2024

Using VistaVision was partly for romance — it was engineered in the 1950s, when most of the film is set. “An absolute no-brainer,” Corbet says. It was also practical: VistaVision doesn’t require a special lab, whereas 65mm formats can only be developed in the UK or Los Angeles. Corbet jokes that whenever he sends one of his films to a streaming service, it gets bounced back. “We’re so accustomed now to everything being crystal clean in 4k. For me, movies should look like artefacts, something really tangible.”

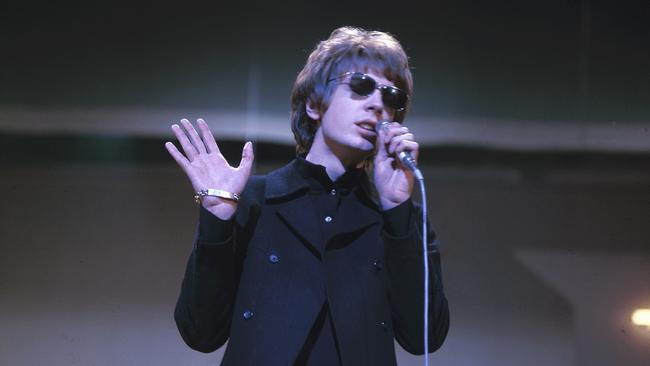

Speaking over Zoom from his London hotel room — where he hilariously wears sunglasses throughout the conversation, he is jet-lagged but otherwise kind and gracious — one immediately gets the sense that this is a director who sweats the small stuff, down to the paper and printing process used for magazines seen in the film.

It pays off. From the film’s very first moments, when the industrial drone of Daniel Blumberg’s exquisite score kicks in, you’re hooked. “Conceptually, we were talking about musique concrete and using slabs of sound to reflect the architecture,” Corbet explains. “There’s only seven minutes of brutalism in the entire movie, so it was important to represent the architecture, not just present it. For me, the movie itself is brutalist — a big, heavy, outsized object.”

This is the first of Corbet’s films not scored by Scott Walker, the former Walker Brothers teen idol turned avant-garde provocateur, who passed away in 2019. “When Scott died, it was a huge blow for personal reasons. Up until that point, it was hard for me to imagine not finishing a movie with him,” Corbet says.

Toth is fictional, but his story — of an artist, like architect Marcel Breuer, underappreciated in life but revered in twilight — is familiar. Corbet can’t help but think of Walker. “I think of what he went through for many years, when nobody paid his work any mind.

“The movie encapsulates that idea. It acknowledges the painful reality of life: you struggle to make these projects, and once you’ve reached the peak, you can’t remember why you’ve been climbing for so long.

“There’s something quietly devastating in the fact that by the time everyone acknowledges and appreciates the work, it’s frequently too late.

“I’ve been fortunate to have as much support as I’ve had over my career. Of course, I struggle — but I’m only in my 30s. For most artists, though, it doesn’t go that way. Most musicians live in a studio or one-bedroom apartment until they die.”

Corbet remains hopeful the film will find an audience. “If the film functions even a little bit commercially, it would help the culture shift along,” he says. “It’s a slightly game-changing metric for the powers-that-be — a 3½-hour movie from a filmmaker very few people have heard of. It’s hard enough when you’re Scorsese or Nolan.

“Hopefully, it creates space for challenging works about adults for adults. That’s increasingly rare.”

The Brutalist is out in Australian cinemas.