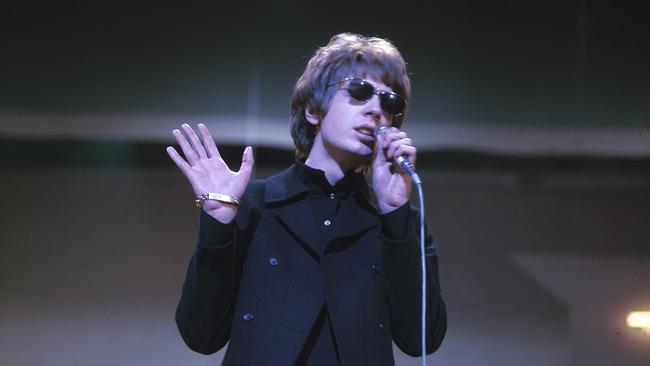

Sun sets on antihero Scott Walker

Scott Walker was an influence on everyone from David Bowie and Bryan Ferry to Radiohead and Pulp.

Scott Walker. Musician.

Born Ohio, January 9, 1943. Died London, March 25, aged 76.

-

Reclusive, enigmatic and determined that the “real” him should remain private, Scott Walker contrived a brooding mystique of philosophical angst, which he drew around himself like a cloak, although his devoted fans detected a shining halo and hailed him as a genius.

His music was an influence on everyone from David Bowie and Bryan Ferry to Radiohead and Pulp. Yet he spoke of the dark baritone voice that made him one of the most evocative crooners of his generation as if it were a separate entity, a force of almost spiritual power that had nothing to do with the body out of which it came.

“It’s a beast all on its own. I think of it as another thing, another person,” he said.

“The great thing about it is that I don’t use him for ages, then I can open the box and take him out, and there he is.”

If the later Walker was much given to such existentialist musings, his origins as a pop star were conventional enough when he emerged in the 1960s as the lead singer with the Walker Brothers on such heartbreaking hits as Make It Easy on Yourself and The Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine (Anymore).

None of the group’s three members were siblings and none of them was named Walker, but their smouldering good looks made them instant pin-ups. The Walker Brothers were in their way the world’s first boy band and at the peak of their success their fan club reputedly had more members than that of the Beatles.

Mobbed by screaming girls on tour in 1966, Walker suffered severe concussion, forcing the group to cancel dates. Unable to deal with the maelstrom around him, he was later found unconscious in his gas-filled apartment in a presumed suicide attempt.

It was the first of several breakdowns and shortly afterwards he disappeared on the eve of the group’s Australian tour and hid himself away in a monastery on the Isle of Wight. He was forced to flee its sanctuary when the press discovered his whereabouts and the monastery was besieged by screaming fans.

To the surprise of nobody, the Walker Brothers broke up after a sellout tour with Jimi Hendrix, Cat Stevens and Engelbert Humperdinck in 1967. “There was a lot of pressure. Everyone relied on me and it got on top of me,” he said. “I was not cut out for that world. I loved pop music, but I didn’t have the temperament for fame.” He certainly did not. He not only suffered stage fright, but he seemed to look down on the teeming prospect of popular music with something approaching contempt.

His first act after the group broke up was to disappear again, this time to Moscow. With characteristic over-seriousness, he was anxious that his fans should know he was not going for a holiday but “to study Russian culture”.

Although his erratic character was ill-suited to pop celebrity, it was also evident that he was by far the most talented of the three Walker Brothers and the best equipped to launch a solo career. The point was reinforced when his solo debut, released at the end of 1967, charted at No 3, outstripping a simultaneously released collection of the Walker Brothers’ greatest hits, which barely scraped into the Top 10. The album marked a dramatic change of direction and launched him as a troubled, moody chansonnier channelling the spirit of Jacques Brel.

His interpretation of Brel’s Jackie gave him his first solo hit single, but it was the romantic ballad Joanna that in 1968 gave him his biggest solo hit.

Further albums, titled Scott 2, Scott 3 and Scott 4, followed in similar style as Walker blossomed as a songwriter, combining introspective lyrics about sex, death and the universe with smart, subtle symphonic pop arrangements.

Yet at the same time he was presenting a weekly television series for the BBC, which marketed him as a family entertainer and middle-of-the-road balladeer in the tradition of Matt Monro and Jack Jones.

Walker had an entirely different image of himself — as a heavyweight musical intellectual. The gap between his TV audience and the records he was making became an unbridgeable gulf with the release in 1969 of Scott 4.

Full of dense philosophical references, the record is now regarded as a masterpiece. “In a song I look for what I consider to be the truth. The people following me don’t want sugar-coated rubbish,” he said. That, however, was what many of them did want. The album failed to chart and cemented Walker’s image as the misunderstood outsider who was not prepared to play the pop game.

His record company was predictably furious that its prize asset was turning his back on his primary audience. “They called me in and carpeted me and said, ‘You’ve got to make a commercial record’,” he recalled.

Caught between the demand for commercial success and his desire for creative freedom, the 70s became a lost decade in which he cut an unhappy figure, releasing unsatisfying albums of covers and joining a cash-motivated Walker Brothers reunion that produced a hit single, No Regrets. He was meanwhile keeping his melancholic demons at bay with marathon whisky binges. “I think I did temporarily go crazy, because I don’t remember the period at all,” he later admitted.

He concluded, with hindsight, that he had been “acting in bad faith”. “I should have said, ‘OK, forget it’, and walked away. But I thought, if I keep hanging on and making these bloody awful records … but it went from bad to worse.”

Just when it appeared his career had stagnated irretrievably, interest in his work was reignited by the release of the compilation Fire Escape in the Sky: The Godlike Genius of Scott Walker. Containing songs from his four late 60s solo albums and compiled by Julian Cope of Liverpool post-punk band the Teardrop Explodes, the title was not intended to be ironic: while nobody was looking, a full-blown cult had grown up around Walker and his singular body of work.

It led to a six-album contract with Virgin Records, starting with 1984’s Climate of Hunter. An extraordinary collection of avant-garde textures and intense, sometimes morose compositions, the album was well received critically. One reviewer applauded him for daring to record “the most terminal songs ever written”. Yet it was reputedly the lowest-selling album in Virgin’s history. “This is how you disappear,” he had sung on the album’s opening song — and Walker did.

The follow-up, which had the working title Abandoned and which was to have been produced by Brian Eno, was scrapped and his contract annulled.

It was another dozen years before he was heard from again. By the time he reappeared in 1995 with the album Tilt, he had dispensed with the verse-chorus format of conventional pop in favour of a minimalist, atonal approach that one critic likened to “Andy Williams reinventing himself as Stockhausen”.

Asked in a rare interview what he was up to, he mysteriously replied: “Who knows? Hanging out. Doing a little travelling. Nothing constructive.”

He told another interviewer he had spent his time “in pubs watching guys throw darts”. It subsequently transpired that he had briefly worked as a painter and decorator and taken a course in fine art at a north London college.

There were sightings of him cycling around west London, where he lived with his long-term partner, Beverley, who survives him. In 1972 he married Mette (nee Teglbjaerg) and had a daughter, Lee. They and Lee’s daughter Emmi-Lee also survive him.

Another decade passed before The Drift in 2006 and a further six years before Bish Bosch. Positively reviewed, but hardly accessible, it included a 22-minute track titled SDSS1416+13B (Zercon, A Flagpole Sitter) and lyrics such as “Earth’s hoary fontanelle weeps softly for a thumb thrust”, which were proof either of his genius or his pretension.

He denied that he had deliberately opted to make his work inaccessible to the masses. “I’m writing for everyone,” he insisted. “It’s just that they haven’t discovered it yet.”

Born Noel Scott Engel in Hamilton, Ohio, in 1943, his father, Noel Walter, was a manager in the oil industry and his mother, Elizabeth Marie (nee Fortier), was Canadian. They divorced when he was six.

He made his first stage appearance in a Rodgers and Hammerstein musical in New York aged 10, learned to play the double bass at school and studied music at college.

After moving to California in 1959, he made several solo records under the name Scotty Engel in the anodyne style of the late-50s “whitebread” teenage stars. He formed the Walker Brothers in 1964 with Gary Leeds and John Maus, taking their name from a fake ID card Maus was using.

The trio relocated to London in 1965, a decision in part forced because Engel had received his draft papers and had no desire to fight in Vietnam. He never returned and made London his home for life.

“I like people, but sometimes I can’t wait to get away and be on my own again,” he said. “Solitude is like a drug for me. I crave it.”

The Times

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout