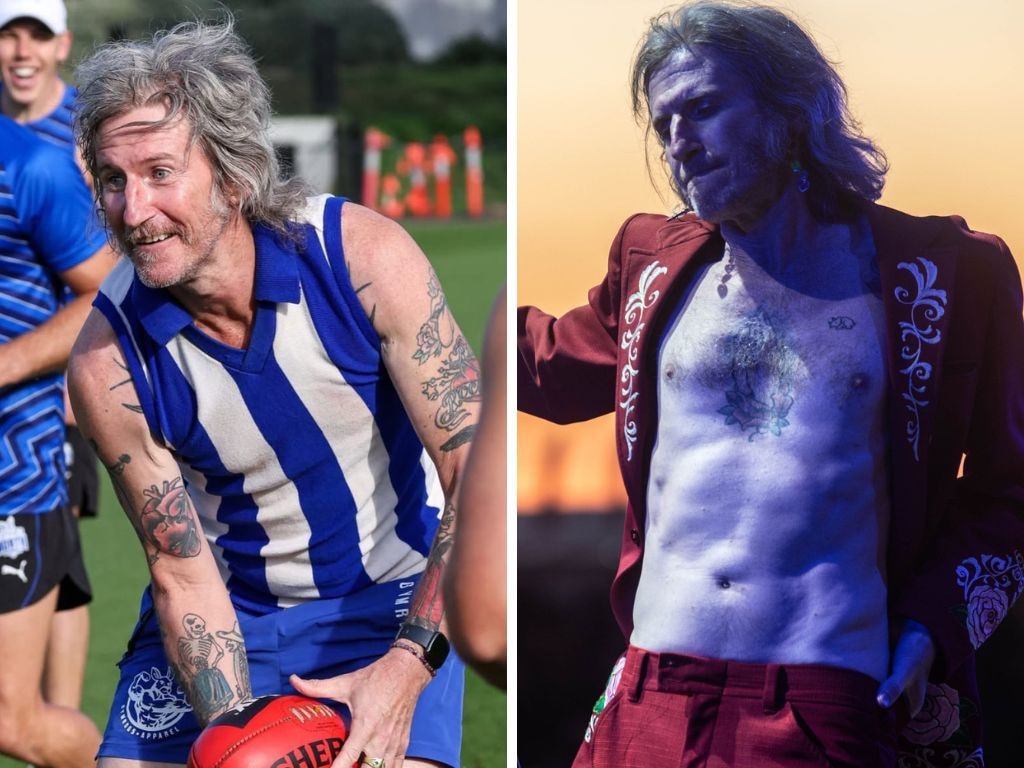

Interview: Tim Minchin on health, fitness, nudity, drinking and body image

The singer, songwriter and actor speaks about his lifelong love of fitness, wrestling with distorted self-perception, learning to value his ‘body that works’ and why he believes ‘continuity is king’.

Australian singer, songwriter, composer and actor Tim Minchin, 49, speaks to The Australian about his lifelong love of fitness, happily appearing nude on screen, wrestling with distorted self-perception, learning to value his “body that works” and why he believes “continuity is king”.

When you’re on tour, Tim, what have you learned about staying fit?

I’ve got this natural competitive instinct; not in that I need to win but competitive in that once I’m observed, I feel very inclined to prove myself. I mean, that’s basically the core of my personality; that’s probably why I do the job I do. So I love a HIIT class (high-intensity interval training); after this interview I’ll go and do the lunchtime class up the road, and I miss that when I’m on tour.

The other thing I love is running, but as I get older I can’t rely on it so much because I get too sore. Then there’s the diet thing, which is really hard, and then alcohol. I’m starving when I get off stage, and I don’t eat much before, and I’m buzzed, and I’ve had a couple of drinks on stage – and now I just want to smash the rest of a bottle of wine and eat shit, you know? It’s really hard, and as I get older I’m adamant I’m going to get better – but I only get incrementally better.

I’m turning 50 this year and this is probably the biggest tour I’ve ever done because even though I did arenas (in 2010), there weren’t many. This is 35 3000-to-5000 seaters, in England and in Australia. I’ll have to look after myself, so what sort of exercise do you do, how do you not eat crap at the end of the night and how do you curb your drinking? Connected to all that is the mental health stuff and making sure you’re sleeping.

Your new album, Time Machine, includes new recordings of old songs, including closer Not Perfect, which was written when you were “29 and 12 months old”, as you sing in its lyrics. Were you less interested in health and fitness in your 20s than you are today?

No, I was quite a serious sporto: I played second-grade hockey and that was a bigger part of my life than music or theatre or anything when I was a teenager. I played hockey five times a week and I did that all into my 20s. The thing I’m best at in hockey is that same “not give up” engine; I was a good distance runner, and so I would be still running at the end of the game when everyone else was shattered, and that was my superpower. That didn’t go away; I’ve never gone six months without running regularly. I doubt I’ve gone six weeks.

The time I really let it go is actually just after that song (was written), because you have a baby and you just can’t make time for yourself. I’ve always been really interested in cardio; I’ve always not wanted to let go of my ability to run 10Ks. And I didn’t drink as much then as I did in my 40s, and I’m coming back to that now; but I didn’t get that habitual every night drinking until my late 30s. It was really getting known, and the pressure of touring, and I think probably my drinking is just a gentle medicinal habit born of how I come down off the end of my days.

So I was pretty good back then. I was less aspirational. I think I was like: “Oh, well, I’m a weird-looking guy.” These days I’m like: “I’m going to be on telly with my shirt off in three months.” It’s much more about how I’m perceived, and despite not being a “leading man” type, I do get roles where I’m not meant to be Seth Rogen; I’m meant to be strong. Now it’s tied up in my brand and perception, and ageing. I didn’t have a great relationship and still don’t have a great relationship with how I look, so my fitness was much more internalised. As in, I was only trying to please myself, trying to keep my own demons at bay; now it’s all more public.

In your song Not Perfect, you briefly discuss body image: “And the weirdest thing about it is / I spend so much time hating it / But it never says a bad word about me.” Presumably you were very fit at the time that was written, but you weren’t happy with how you looked. How do those two things coexist?

I don’t know. I hate the inclination these days to publicly declare your victimhood or pathologise your normal human feelings. In the past I have said something like “I think I’m mildly body dysmorphic”, and I regret saying that stuff because we shouldn’t pathologise the normal range of feelings you have. And I would never presume to know what someone with proper disordered self-perception feels. That’s my disclaimer.

But just coincidentally, I have the lyrics of my latest song in front of me, which is called Peace. It’s a song about what I need to feel peace. And it starts with: “When the long day is over and the weary sun folds itself into the sea / And the doors are all locked and the deeds are all done, you will come to me.” It’s personifying peace; a bit like Night Will Come in Groundhog Day.

And then it says: “When the bets are all off and the beasts are all fed / And when the boxes are all ticked and when that boulder is finally perched on the hill”. And then it says: “When every critic who’s ever criticised me is vanquished / When the heads of my haters are on a pike and burnt in a fire …” It just gets like, “Whoa, bro!” It’s saying: this is sometimes how I feel. I can’t be at peace until everything is solved.

And one of the lyrics in that song – the most vulnerable, slightly awkward lyric – is: “Once I can play half as well as they think I can play / And all my disdain is applauded away / And the mirror stops playing its carnival games”. So the bit of me that has a really difficult problem with my physical self hasn’t really changed. I’m just more able to go: “Oh, that’s just that feeling.”

I’m really fit for my age now, and because of this 20-year anniversary tour I’m looking at all this old footage of me and thinking: “Oh my god, you were fine, and you f..king hated yourself. You were so convinced of your own unattractiveness.” But I can say that and know that I was fine; I knew at the time, even, that it was just bullshit ego fragility.

Again, I don’t want to pathologise it – but unfortunately, in the last 24 hours, I’ve had a real moment of “Oh my god, what’s happened?”. It’s like an illusion. It’s quite interesting. And that’s why I talk about it, because I think it’s more common in women to have a strange relationship with your shape – but I don’t think it’s uncommon in men.

I don’t think it is either, but it’s less common to hear it spoken, so thank you. The original song may have been helpful for men to hear back then, and it will be this time around too because part of the point of this project is to reintroduce these songs to an audience who may not have heard them, correct?

That’s right. I’ve had this weird career where I’m good at “live”; people come to see me live. Up until Apart Together (2020), I never had a record deal. I’m not played on the radio, partly because my songs are long, partly because they’re sweary – but mostly because they’re not pop songs. They’re not easy eating. They’re complicated and they’re bookish and wordy. It’s just a different genre from most of the stuff we’re fed; I’m not being disdainful of that.

But because I got known as a “live guy”, a lot of these songs have been recorded in concert, and some of them are really well-known. But it’s so weird as a songwriter to go: “I have never nailed that song in the studio. I’ve never given it the right to be played until it’s perfect, mixed so it’s lovely, and produced.” I felt I owed those old songs production, and then owed the songs that have been heard very rarely the same treatment, because why the f..k don’t I get to properly studio-record my songs, just because I’ve had this weird upside-down career? Most artists record first and then go and try and take their record to the world via the stage. I’m the opposite.

The body image discussion reminds me of the character you played in the TV series Californication, Atticus Fetch, who spends much of his time on screen shirtless. What did filming that character on that show do for you?

Well, I’ve been full-frontally naked on a long shot in The Secret River (2015) and shirt off a lot in Californication (2013); I didn’t get nude in Robin Hood (2018). I was very nude with my bum showing in Upright (2019) and then a boxing scene, shirt off. Basically it’s almost in my contract, and that’s the weird dichotomy of this; I have very little shame. So even though I look in the mirror sometimes and really don’t like it, I have no shame about my body. I just don’t have any fear of being nude in front of people, partly because, on one level, I know I’m quite fit. This is the f..king weird thing about it, you know?

And Californication was the first time the script (said): “He’s naked” or “He’s wearing nothing but a guitar” or “He opens the door nude” or whatever. And I went: “Oh, I know what to do about this: I’m going to f..king lose five kilos.” I don’t have trouble taking the challenge, I just need the drive. And so in six weeks you’re going to be naked on a show that 10 million people will see? It’s a pretty good drive.

Part of the reason I like acting is because it gives me a motor to keep me honest in this way. That’s a bit f..ked up, isn’t it? Even in (Disney TV series) The Artful Dodger, I’m playing a baddie; he doesn’t need to be fit at all. In fact, he’s kind of a grotesque character, but I just go, “Oh, I’m on telly next month – let’s pull it back together.”

I don’t think that’s f..ked up; it’s an external reward system beyond your own discipline, or your own desire to look a certain way. That’s helpful, and clearly it’s working for you.

Well, you’re right, but you’ll notice nearly everything I’ve said about my body has been about how it looks and its aesthetic. That in itself is a terrible message because Not Perfect had it right: “I spend so much time hating it / But it never says a bad word about me.”

My body is this amazing, healthy thing that has never let me down, barring a couple of injuries and asthma. Obviously it’s had its moments, but how lucky am I to have a healthy, functioning body, in any range? I could be 10 kilos lighter or 15 kilos heavier, and I’d be still in the range of being lucky and healthy, or healthy enough.

What’s really hard about this is making sure your kids don’t inherit your f..ked-upness, because I don’t know where mine comes from. I could theorise, be Freudian about it. I think a lot of it’s to do with being a performer, and being in an industry where the most common thread through people who get the famous is that they’re good looking; they’re preternaturally handsome.

So I’m in this world where nearly everyone I see on a red carpet is really hot, and it f..ks with normal-looking people. But I don’t want my kids to think any of that matters – and I don’t want your audience to think that I think that’s what matters. I’m just being honest about my shittiness. And I have a whole level which is very cognisant of the fact that aesthetic is not what health is about, and that using an aesthetic paranoia to drive my health – there’s something broken about that.

The good side is, I’m a really healthy 50-year-old. I’ve got a lot of peers – not in the industry – who are just happy and really out of condition, and that’s fine, too. I try to teach my kids that your body’s a vessel that you owe respect. You don’t trash it. It’s in my university speech that a lot of people know: “Your generation is probably going to live to 110. Your body’s your gift. Don’t f..k it up; don’t party it away too hard, because you want it to be serving you in 80 years.”

Yes, the value of exercise was one of the nine “life lessons” you mentioned in your great 2013 University of Western Australia speech while receiving an honorary doctorate. Why was that important for you to include at the time?

Oh, I don’t know. I wrote that speech very quickly, and like a lot of the good things I’ve done in life, it benefited from not over-thinking – which is a positive way of framing my unbelievable capacity to procrastinate. It wasn’t called “nine life lessons”; someone else gave it that title. It was just an acceptance speech. I knew it was pretentious to frame it as “lessons”; I was self-aware in that regard.

But I’m not surprised at all that 38-year-old me put that in the top 10 things I think matter. I mean, I hope it didn’t come across as, “Stay skinny, kids!” It really is about being almost 40, as I was when I made that speech, talking to 19 and 20-year-olds and going, “What have I learned?”

I just know people who, in their 20s, didn’t find a habit of eating well, or being careful with drug use or alcohol use, or exercise. They became sedentary. Those “lessons” are half a list of things I aspire to be better at – “define yourself by what you love” – and all those things that I’m like, “I wish someone had told me that then, because I’m still struggling with this”. And the other half of the list is things that I’m glad I have done and I’m proud of, including the primary message of incrementalism: just focus on what you’re doing and be really good at it. Don’t think, “I’m going to be famous” – just do a good job.

That was something I had done intuitively and gone, “I think that was right.” And the other thing was – because I’ve been very lucky with my love of sport, and my body that works – I have always been in a habit of doing exercise, and I wanted to pass that on as a “thumbs up” thing I’d done, as opposed to these other things, which I wish I’d done better. Both are wisdom, right? As you parent, your parenting wisdom you could split between “things I’ve done right and I want you to do too” and “things I’ve done wrong, and I don’t want you to do; I want you to do the other”.

Thank you. Last: what have you learned about maintaining relationships for your wellbeing, particularly when you’re away on tour for weeks at a time?

The fact that I’ve been married for 23 years and have had this huge, significant relationship in my life with Sarah … We grew up together. We got together when I was 17, I was married at 26, and so my relationship with Sarah has bridged every stage, from being poor and not knowing what I want to do, to getting a lot more success than we could have dreamed, and Hollywood, the ups and downs … I can’t imagine what my life would be like without that.

Putting aside whether or not it’s a fantastic relationship, and we love each other, and make each other laugh and have good sex and all that; I’m not talking about the quality of the relationship. Just the fact of continuity, loyalty and knowing that there’s someone who loved you long before the “likes” came along, and with whom we always knew we wanted kids. Continuity is king in my world. I can’t imagine what it’d be like to get proper famous, like Ed Sheeran or Brad Pitt; I don’t know how you’d have your mental health, because it’s very discombobulating.

And so to being on tour: I love my co-workers and my collaborators. I don’t have an entourage; I’ve never been someone who’s got super-close mates, because I left Perth 22 years ago and I disconnected myself. What I’ve got is not just my wife but my whole family; I’m incredibly close to my siblings and my dad, and I communicate with them all the time. I sometimes don’t feel like I quite have wing-men and women with me when I’m out in the world, even though I have agents, managers and tour managers who I adore and who would do anything.

It sounds like you have strong attachments, Tim, particularly with your family.

Without a doubt. I mean, all the data shows community – feeling like you’re contributing to it, and that it contributes to you – is the greatest correlate with happiness, wellbeing and longevity.

That’s why religion comes up good; religion has all sorts of f..king problems, but if you want to live long and feel like you’re part of a community, you should be part of a church. That’s why I care about art, because that’s my church. Church for boho people is we gather together, share ideas and have communities. That’s why art is important in a secular world as well.

Tim Minchin Time Machine is out now via BMG Music. Minchin’s 16-date Australian tour begins in Melbourne (October 31-November 2) and ends in Toowoomba (December 7). Tickets: timminchin.com

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout