The making of Bert Newton

Bert Newton was brilliant for a very long time. But there is no longer a place in this new storytelling universe for one of TV’s great pioneers.

The stylishly produced observational documentary series Who Do You Think You Are? returned last week for its 11th season, the first episode featuring indefatigable television presenter Lisa Wilkinson. Other subjects in coming shows include actor Cameron Daddo, former politician Julie Bishop, actress Kat Stewart and comedian Denise Scott.

But this week’s episode is particularly interesting as it features Bert Newton, who for more than 5½ decades made Australia laugh, our greatest clown, a veteran of radio, TV and, towards the end of his career, theatre. He was the consummate TV host, presenter, compere and personality, the last survivor of the medium’s beginnings in this country when the “magic lamp”, as it was known, became part of Australian life at alarming speed, heaping thousands of images upon a sleepy national imagination.

We last saw him on TV in a much publicised misadventure when in 2018 he appeared at the 60th annual Logies to present the Graham Kennedy Award for most popular new talent. There was a self-mocking gay slur in his improvised remarks and several crass comments about Kennedy, with whom he once formed one of local TV’s great comic partnerships.

It had been a long time since Newton appeared regularly on TV, the last occasion a Nine format called 20 to 1, in which for five years he counted down momentous moments in the history of popular culture.

But amid the whiz-bangery of digitally realised TV he seemed at times like a hologram, stiff and constrained, stuffed into a too-tight suit. He eventually parted ways with the Nine Network in 2014 when his rolling contract expired, after an association spanning 50 years.

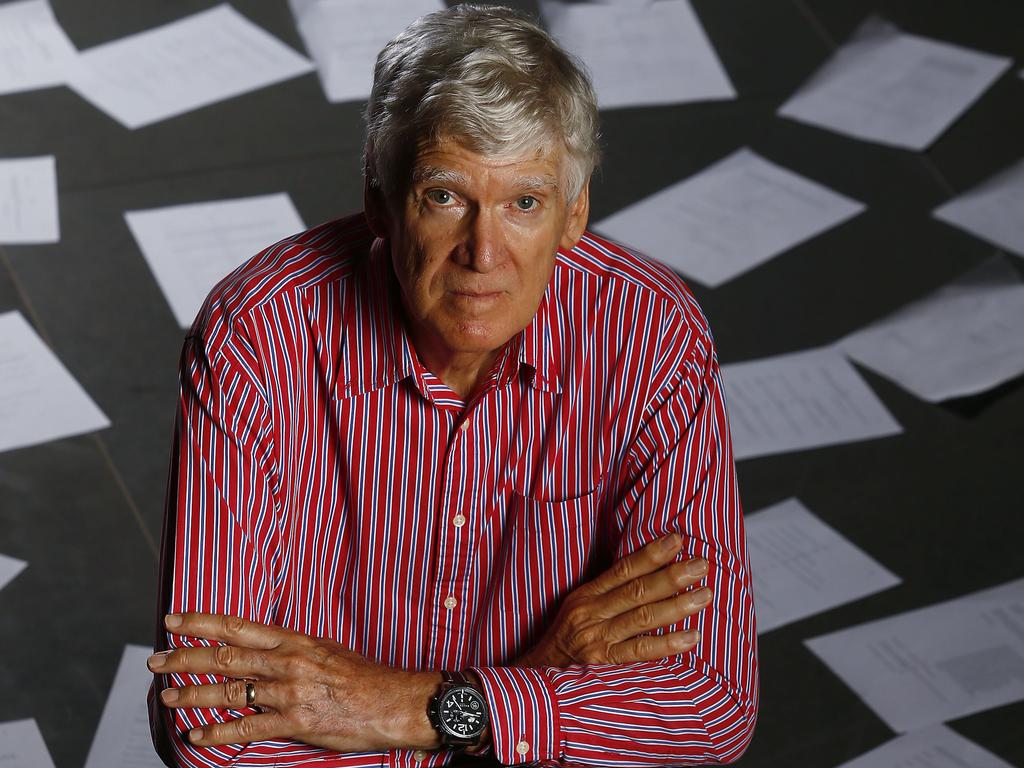

So it’s a pleasure to watch him in this genealogical show where at 81 he’s still laughing gently at himself, as though he can’t really believe he is still here on the telly, still working.

“If there was one word to describe my life so far, the word would be lucky,” he says at the start. “I’ve been able to do all the things I dreamt of professionally, but also personal — to have such a beautiful wife, Patti, two wonderful kids, and a second life with grandchildren. This is pretty close to perfection.”

Patti is of course Patti McGrath, the young soubrette he married in the only televised wedding in Australian history, a relationship that became a double act without peer, kindred spirits in the same orbit, their marriage celebrated for its warmth and longevity, and a staple of Australia’s celebrity-obsessed tabloid magazines.

In the program he’s in search of the history of his father, Joseph James Newton, known to all as Joe, who died in Melbourne’s Heidelberg Repatriation Hospital in 1950 after constant bouts of malaria after serving extensively in the army during World War II. Bert Newton was 11 years old. “The only thing I could complain about is that I didn’t get to know my dad all that well,” he says as his journey begins. “Dad was a man who came to the door and he was a stranger to me.”

When his father arrived home from New Guinea in 1945 at the end of World War II, after 1000 days of battle, the six-year-old didn’t recognise him and wouldn’t let him through the door of their terrace home in Fitzroy; and until his death they remained somewhat distant, his father “a man who wanted to be alone”. Like so many veterans Joe Newton rarely talked of his war and his son had little idea of what his service had involved.

“As a kid I can still recall walking into the lounge room and Dad would be there all by himself — he seemed to be in a world of his own,” Bert Newton says.

But now Newton wants his own children and grandchildren to know the family background that remains in the shadows to him still: “I’m opening a door that hadn’t been opened before and if there is bad news in there it’s too late for me to do anything about it.”

The journey takes him back to the Fitzroy where he lived with his mother until he was in his 30s, a trip that brings tears, and on to the War Memorial in Canberra and eventually to the hospital in Heidelberg where his father died. Whenever Joe Newton did talk of his war experience his stories always ended with, “it was no picnic”, Bert Newton recalls, and that’s certainly what he discovers in a story of service and heroism.

But then there is his mother’s history to unravel as well, Newton retaining no memory of his grandmother or grandfather. And what an adventure that turns out to be for the veteran entertainer, linking him to a trailblazing feminist pioneer and the tale of a bare-knuckle street fighter who grew tired of life.

As is always the case with this program, it’s produced stylishly and photographed with some cinematic polish, the drone shots especially effective. And as always as a TV show it is structured around the classical narrative structure of set-up, development and resolution, artfully blending the history documentary with the detective story. It’s a classy piece of reality TV appealing to our thirst as viewers for authenticity — even though the setups are contrived and the stories tightly edited.

And the researchers have found telling archival footage documenting Newton’s career, including some magical scenes of his first performances with Kennedy at the beginning of what became a legendary double act, thriving on a constant display of riposte, slight and mockery.

And Newton is entertainingly at the centre of his own story here, his face rounder than ever, like an old friend with whom we are always delighted to catch up. (As novelist Barry Oakley once wrote, “if his namesake Isaac gave us the law of gravity, Bert riposted with the first law of levity: when you have a face like a pie chart, what can you do but laugh.”) As the footage with his family shows, Newton is still quick with a joke or a bit of slapstick at gatherings with his five grandchildren. His language is that of a different era, a little orotund and courtly, the handshake that of a priest, comforting and embracing of frailty. There is entertaining nostalgia in this journey but sadness too. Not just for Newton but for us as viewers too, the generations that grew up with him. This just may be the last time we see him on the screen.

In so many ways his career was a celebration of the traditional and increasingly obsolescent notion of TV as a virtual community, an extended family brought together by the same shows, when we argued with the screen, shouted and barracked, and cackled with ridicule at times so violently we practically tumbled off our sofas.

He really was a kind of social presence almost from the time TV began in this country, one of TV’s best known and revered chatting conduits, those cheerful presenters who, by talking to the camera, negotiate a peaceful compromise between those of us watching and those who are interviewed, or who perform or compete on the screen. Targets of great affection and an equal amount of derision, they are largely taken for granted, even though the subject of radio, internet, magazine and newspaper coverage, and like Newton have careers that have lasted almost as long as postwar TV itself.

Nevertheless, as a profession, TV presenting, routinely ignored, has received little serious attention, not that it ever seemed to really disturb Newton — unlike Kennedy, who often referred to his career in TV as “going second class”, especially when compared to acting, spending his life desperate to be categorised as anything other than a talk-show host.

Kennedy said he couldn’t dance, wasn’t really a singer, and found jokes hard to tell — but he did it better than anyone else. The same, to some extent, was true of Newton. His was a warm, friendly aura and it brought viewers back to him as fashion claimed other personalities. He was there when all his contemporaries evanesced from the screen and then from our lives. He made no demands of us other than to be watched; his was the kind of TV that we watch when there is nothing else happening, not particularly important but regular. And for that we should be grateful.

And Newton was brilliant at it for a very long time. But TV’s new digital landscape seemed to have no place for a portly chap in his 70s, for that increasingly unfamiliar idiosyncratic language; even his voice mellifluous, purring and honking, and that deep resonant laugh seemed so out of place.

When Newton began his long career, we believed that TV shows came beaming into our living rooms like visions from some powerful force, but this decades-old technical miracle has altered its shape in recent years, the one-time devout community of watchers splintering in every direction. And there is no longer a place in this new storytelling universe for one of TV’s great pioneers.

Who Do You Think You Are? Tuesday, 7.30pm, SBS.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout