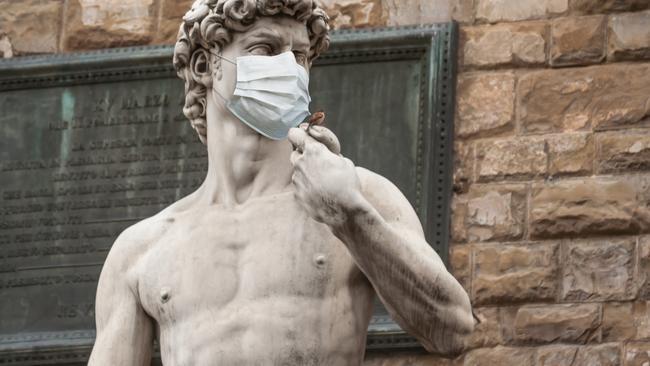

How Florence beat the plague

From wet markets to penalties for breaching lockdown, the world has been through pandemics before.

Betta d’Antonio was only trying to mend her son’s pants when the police in Florence booked her for breaking the lockdown. D’Antonio, a wool weaver, admitted rigging up a pulley “because my son had asked me to mend a pair of trousers, so I let down the basket so that he could put them inside for me, since he was locked up and quarantined in the rooms below mine”. When a city official spotted the basket dangling outside Betta d’Antonio’s open window, she was arrested and thrown in jail.

Another Florentine citizen, Antonio di Francesco Trabellesi, was out exercising when Monna Maria, a widow, “called out and asked me how I was. I said to her that I was fine, and while I was talking to her the police officers came and took me to prison”.

A month ago? Two months? Both stories are nearly 400 years old, dating back to the plague that struck northern Italy in 1629. They are drawn from Florence Under Siege: Surviving Plague in an Early Modern City, by John Henderson, professor of Italian renaissance history at Birkbeck, University of London.

Henderson’s book was published last year, just a few months before the world had heard of COVID-19, but the stories he recounts — of lockdowns and cover-ups, civil disobedience and miracle cures — echo the news from Wuhan, Washington and Bondi Beach.

Said to have been brought by German mercenaries, the plague reached Lombardy in the autumn of 1629, died down over the winter and roared back the following spring. Milan, Turin and Verona were early hotspots, but it was the plague’s arrival in the city of Bologna that really alarmed the Florentines. Like the party bosses in Wuhan, the Bolognese authorities acted quickly to suppress public discussion of the contagion — Henderson notes that “a general prohibition had been issued that on pain of death nobody was allowed to speak of peste”. As a result Florentine officials “realised they could not actually trust their Bolognese colleagues”.

By June 1630 the crisis in Bologna was so serious that the Florentine authorities moved to create a cordon sanitaire around their city. To enforce the travel bans, mounted troops were sent to patrol the mountain passes over the Apennines to “prevent all commerce or communication with the Bolognese”. Travellers without a valid health pass who refused to turn back were liable to be shot.

Contact tracing was an early priority. Would-be visitors were required to confirm their name, their father’s name and surname and their place of origin, and to give a detailed account of their recent movements. Border guards took careful note of physical characteristics, such as age, height and “whether bearded or not”.

RELATED: Why the elbow bump is the most ridiculous greeting in history | A pandemic good for art? The Spanish flu tells a different story | Can the hairdresser do my colour yet? How corona-recovery looks

But travel embargoes, and the banning of fairs and markets to prevent mass gatherings, failed to stop the disease from spreading. Henderson records that in September 1630, 600 plague victims were buried in mass graves outside the city walls. In October the monthly toll passed 1000. It doubled again in November. In January health officials ordered a citywide lockdown for 40 days under penalty of fines, imprisonment or worse.

Wet markets? In June 1630 Florentine health inspectors targeted the city’s butcher’s shops. Jachopo di Bartolomeo, a butcher at the Canto all Paglia, was found to have a “cesspit full of putrid entrails and of blood and putrid excrement mixed together”. According to the inspectors this noisome material created “a great fetor and stink … which could lead to serious disease”. The recalcitrant butcher was sent to a secret prison run by the city’s health board.

“We either save avoidable deaths & destroy society OR accept avoidable deaths & save society. The moral dilemma of our time,” Australia’s former foreign minister, Alexander Downer, tweeted a few weeks ago. It was the moral dilemma of their time too.

With the lockdown in force, many could no longer work. Essential workers — especially those involved in selling food and in the city’s textile industry — were allowed to keep their jobs, although they had to live in their workshops and were forbidden to go home. Blacksmiths could keep working, as long as this did not lead to “large groups” congregating at their workshops; wine dealers could sell booze — but not sit-down meals.

Grand Duke Ferdinand instigated a financial rescue package to counter the economic damage caused by the shutdown, funding relief of the poor and providing food and cash subsidies to those under lockdown, while continuing to pay the salaries of public servants. Henderson records that the Grand Duke helped the jobless by underwriting a series of public works, while also providing cashflow support and JobKeeper funding in the form of 18-month interest-free loans to wool, silk and linen merchants.

The city authorities did their best to clamp down on anyone seen to be taking advantage of the epidemic, with profiteers and fraudsters named and shamed. Gravediggers were quick to take advantage of improved trading conditions. Henderson notes that miscreants were “condemned to ride a donkey backwards, with a card around their necks on which their crime was described” while fellow citizens hurled abuse as well as rotten fruit and vegetables.

Others came in for harsher punishments, such as the Strappado, in which the offender was “hoisted up with a rope wrapped around the armpits and then dropped, leading to dislocation of arms and shoulders”. Depending on the gravity of the crime, the Strappado could be administered more than once. Henderson relates the case of a baker, Lorenzo di Raffaello, who was contracted by the city’s health board to make and distribute bread to the poor. Di Raffaello’s loaves were found to be three ounces lighter than the standard weight and he was “twice subjected to the Strappado in public, with a loaf of bread at his feet”.

Many bridled at the restrictions on physical movement and economic activity. While the city was under total quarantine, six people were discovered to have flouted the lockdown. Health officials were tipped off when an informant reported that the group was making a lot of noise — “un mezzo bordello” — outside. The six were tried, found guilty and whipped in public.

Australian police have come in for criticism for their heavy-handed application of social-distancing laws, but as an early 17th-century Tuscan citizen might have said, “that’s not draconian — this is draconian”.

Meanwhile, parish priests were allowed to stand in the street and hear confessions through doors and windows, and the pope gave permission for portable altars to be set up on street corners “so that the maximum number of people could hear mass”.

With the flattening of the curve, the lockdown was relaxed, only for a second wave of infections to strike. Border guards had become careless. Instructions from the health board for people to stay at home were ignored. Strict quarantines were reintroduced and the second wave quickly burnt itself out. Henderson notes that the “very considerable costs and resources expended on the fight against plague were regarded as worthwhile, because the plague was seen as having been stopped in its tracks”.

Part of the expense was in the bizarre remedies prescribed to patients confined in the lazaretti, or quarantine centres for the sick, which included potions of powdered pearls and “oil of crushed scorpions in Greek wine” — but, apparently, not disinfectant.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout