A pandemic good for art? The Spanish flu tells a different story

Many famous artists suffered during the last deadly pandemic, the Spanish flu but were reluctant to openly engage with it

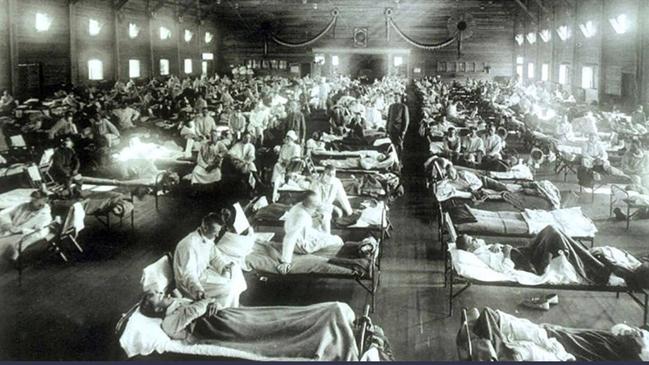

In January, Elizabeth Outka released her book about how the 1918-19 Spanish influenza pandemic affected the lives and works of literary giants including Virginia Woolf, TS Eliot and WB Yeats. The American author and academic’s research shines a high beam onto largely overlooked links between that devastating epidemic — which killed more than 50 million people — and seminal modernist novels and poems, as well as zombie subculture.

Eerily, just weeks after Outka published her book, Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature, concerns started mounting about a new deadly flu-like disease, COVID-19, which was rapidly spreading from its seeding ground in China’s Wuhan to other countries. And within three months of her Columbia University Press title landing on bookshelves, Outka, an associate professor of English literature at the University of Virginia, developed coronavirus-like symptoms including “the shortness of breath, the fever, the cough”.

By the time we speak, her respiratory illness — which wasn’t coronavirus — “seems to have resolved itself”, though a slight rasp and notes of anxiety linger during this phone interview. What was it like for the author, publishing a book about cultural responses to one of history’s most lethal pandemics, only to find herself living through a new pandemic? “Really rather awful,” Outka replies. “I didn’t mean the book to be as timely as it has turned out to be. This is something that everybody who writes on pandemics says — it’s not a question of if but when, but we hoped it still wouldn’t happen. It’s been very strange and surreal. It’s wild to watch this unfold.”

Despite the Spanish flu’s devastating death toll, Outka’s book argues that the immediate literary response to it was oddly muted and paradoxical: references to the pandemic were “hidden” yet had a subtle, “widespread presence” in key modernist texts including The Waste Land (Eliot’s bleak, epic poem); Mrs Dalloway (Woolf’s acclaimed 1925 novel); and The Second Coming, Yeats’s famously unsettling poem, which he wrote in 1919 soon after his pregnant young wife contracted Spanish flu.

The English literature academic says the pandemic faded from cultural memory largely because it was overshadowed by World War I’s massive loss of life. “When the (Spanish) flu came along, people were beyond ready for tragedy to stop … and so in the literature it became hidden,” she says.

While war deaths were seen as “meaningful sacrifice” there was a belief that “everyone gets influenza”. (Yet the Spanish flu killed more people than World War I.) Even today, says Outka, “we just don’t read for disease. We read for male contests of valour and war, but disease is a little scarier.”

Woolf, Eliot and Yeats all had “intimate encounters with the pandemic”, she says, contracting influenza, battling poor health or watching loved ones struggle as the virus killed millions, including the young and fit. Yet those literary greats did not address it explicitly in their works; rather, she says, the pandemic “sort of went underground” in their writing.

Outka says that Yeats had watched his wife, Georgie, “gasp out what he feels like are her last breaths while pregnant (with Spanish flu) … Dublin is full of funerals and coffins and hearses because there are so many deaths from the pandemic. I mean, it just seems like his whole world is coming apart.” (Georgie Yeats and her baby daughter survived, and this was the only case of a pregnant woman surviving the flu that Outka came across during her five years of research.)

Yeats said The Second Coming, with its “blood-dimmed tide” and drowned “ceremony of innocence”, was about revolutions and wars, and Outka says it also “makes sense” to see it as a pandemic poem. “It reads as a delirium poem,” she says, and delirium was one of the symptoms of Spanish flu, along with bleeding from the eyes, nose and mouth.

Woolf, meanwhile, wrote this bleak entry in her diary in 1918: “We are … in the midst of a plague unmatched since The Black Death.” Yet, like Yeats, she did not tackle the flu pandemic head-on in Mrs Dalloway, despite having contracted a severe influenza that damaged her heart — a side effect of Spanish flu and a malady shared by her titular character.

Mrs Dalloway, says Outka, “feels very much her age and her weariness, and when the bells toll, she and other characters think of influenza. One of the terrible things across England and Australia as well as America was that there were so many funerals for the flu victims that the bells seemed to toll continuously … the bells became a kind of nightmarish tolling and many communities had to stop ringing them.”

She argues that while Woolf structured Mrs Dalloway around a survivor of war and an apparent pandemic survivor, critics and readers usually see only the war — reflecting the larger literary forgetting, “the flu doesn’t count”.

In a recent article published by London museum the Wellcome Collection, American writer Allison C. Meier agreed there was “an absence of (cultural) memory for the Spanish flu, which is especially surprising when the arts were in such an experimental phase, modernism in the early 1900s having upended the visual and literary traditions of the past”. Like Outka, Meier attributes “scarce” artistic responses to the pandemic to “the euphoria of World War I’s end”, even though many European artists died in the flu outbreak.

Among them was Austrian symbolist Gustav Klimt, known for his shimmering “golden phase” paintings, who died of pneumonia in February 1918, while the fate of his young protege, Austrian expressionist Egon Schiele, was even more poignant. Schiele lost his wife, who was six months pregnant, to the pandemic on October 28, 1918. He continued to sketch her and died from the same affliction three days later.

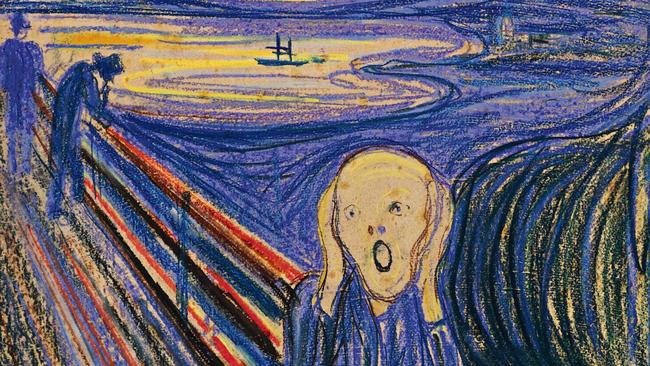

Norwegian painter Edvard Munch created several versions of The Scream in the 1890s and 1910 as an expression of his own anxiety. Yet these talismanic works seemed to foreshadow the coming twin catastrophes of world war and a lethal pandemic. Interestingly, Munch was a notable survivor of the flu outbreak who painted his Self-Portrait with the Spanish Flu in 1919. He depicts himself in an unearthly orange light as an open-mouthed, frail figure, his bed a tortured tangle of sheets.

Walt Disney is another high-profile survivor of Spanish flu: his bout with the illness when he was 17 delayed his arrival at the French war front until after the 1918 armistice. Ironically, this delay may have saved the life of Mickey Mouse’s creator, given the huge number of soldier deaths in France.

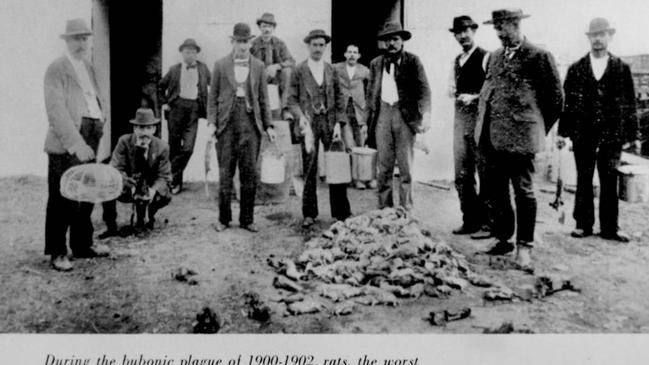

Australian author Ian Townsend echoes Outka’s thesis when he argues that “in Australia, when it comes to epidemic disease, we have a collective amnesia”. Townsend’s 2007 novel, Affection, was set in Townsville during the 1900 outbreak of bubonic plague, and was based on real events and characters. Yet when he visited the north Queensland city to research this book, which was shortlisted for a Commonwealth Writers Prize, he found little remaining evidence of the disease.

Townsend says the 1900 plague “was in centres all around the country and Queensland was particularly affected; Brisbane, Rockhampton, Mackay, Townsville, all these major towns had plague hospitals set up hurriedly and they all had plague cemeteries”.

During his Townsville research trip, he found “most of those plague cemeteries had vanished — people had just forgotten about them, as they had forgotten about the plague”. In a 2007 essay published in the Griffith Review, he wrote: “The terrifying epidemics that have swept through Australia in the past — diseases such as smallpox and plague, tuberculosis and polio … appear to have been erased from our cultural memory. When the plague arrived in Australia in 1900, it produced scenes of mass hysteria and panic. Guns were drawn as doctors came to take people away, (and) people were beaten.”

What underlies the cultural amnesia about such a dramatic and tragic event? “Because epidemics are so traumatic, people want to forget,” he says, adding that there was a stigma attached to bubonic plague because it was a “filth” disease caused by fleas from rats.

Given they affect entire populations, “there’s no reason why we should forget epidemics”, Townsend argues, but “artists tend to reflect the national stories, especially the popular artists. There’s a lot written about Anzac, Kokoda and Gallipoli. Once we forget something, it’s hard to re-remember it.”

Nonetheless, in the 2000s, he believes, “there was a sense something was going to happen” following the outbreaks of severe acute respiratory syndrome, Middle East respiratory syndrome and bird flu, so some artists started exploring this.

Australian Pulitzer prize winner Geraldine Brooks wrote about Europe’s 17th-century plague outbreak in her debut novel, Year of Wonders, in 2002, while 2011 saw the release of Contagion, Steven Soderbergh’s thriller about a viral pandemic linked to bats that starts in China. This month, Soderbergh’s extraordinarily prescient film has raced up the iTunes Top Movies charts.

How will the coronavirus crisis, which is claiming lives and rewriting rules for daily living across the globe, influence the artistic imagination? Outka predicts fiction will emerge exploring what it means to have “two realities to open up — a before and an after — to see what it means to battle something that is invisible, that crosses borders”.

She argues “the history of disease is so often a history of discrimination” with some groups being blamed and ostracised: “(Pandemics) can bring out the very best in people and the very worst.” But, unlike the literary silence that followed the Spanish flu, she believes the 2020 pandemic “will certainly produce a lot of art. We’ll need it alongside the medical cures. We’ve long used art to figure out in times of adversity, and in times afterwards, what it meant.”

Viral Modernism: The Influenza Pandemic and Interwar Literature by Elizabeth Outka is published by Columbia University Press, $57 (paperback), $172 (hardback).

READ MORE: Tom Keneally’s Aussie Dickens connection | Sarah Holland-Batt and the science of love

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout