Great expectations, The Dickens Boy by Tom Keneally

Being Charles Dickens’s youngest son would have been hard work, says Tom Keneally

Early in Tom Keneally’s new novel, Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens, youngest child of Charles Dickens, is introduced to what the author, in conversation, refers to as “chewing the Murrumbidgee oyster”.

“Be firm with him, Mr Dickens. Not tender!” the drover told me.

He had a knife in his hands and leaned over the lamb. I saw him cut the male lamb’s penis off and put his mouth down on the wound to suck out with tobacco-stained teeth one testicle and its accompanying glutinous matter, and spit it on the ground, and then bend again to take up and spit out the second. He smiled at me with mucus-stained and blood-smeared lips. “You could get your father to write about that one," he told me and winked.

That little passage about ovine castration says a lot about The Dickens Boy, an ingenious, hilarious novel from our first Booker Prize winner, for Schindler’s Ark in 1982, and two-time Miles Franklin winner. For starters, young Dickens, approaching 17, is not in England any more.

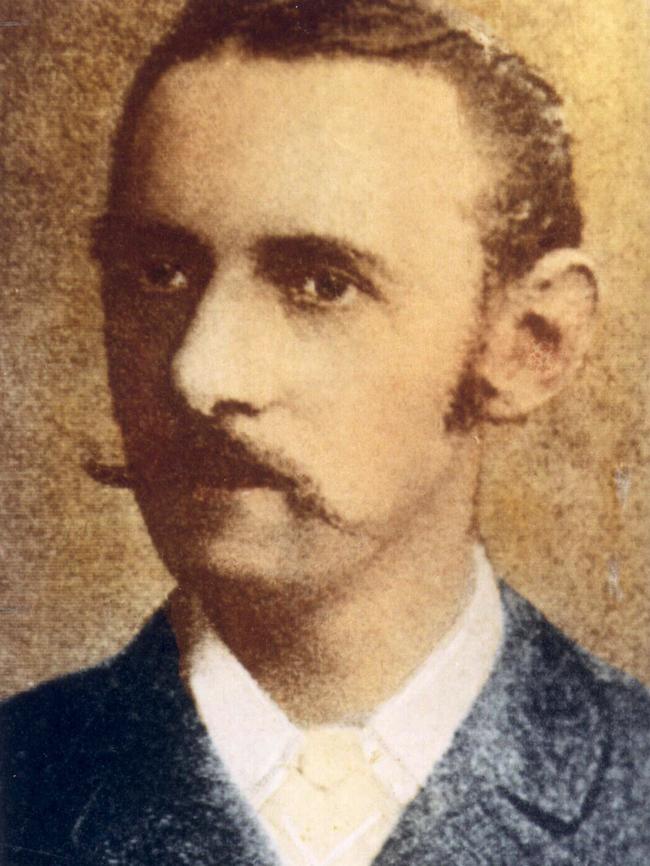

It’s 1868 and he’s been sent to Australia to make his mark as a “colonial gentleman”, following in the footsteps of his older brother, Alfred, who arrived in 1865.

As Alfred tells Plorn, as Edward is known in the family, whenever their father needs to “get rid of someone in his books, he either kills them or sends them to Australia”. He continues, “Where would our father’s plots be, I ask, without death and Australia? The pit at the end of the world you toss useless folk in”.

Plorn and Alfred, who is seven years older, have a serious argument about the “guvnor”, as they call their father. It’s a disagreement that echoes the castration scene. Plorn feels emasculated. Who could ever match, or live up to the expectations of, such a famous father?

He has an extra, hidden reason to feel inadequate. He has not read one of his father’s books. He has tried but never succeeded to “penetrate those armies of paragraphs”. The books are as unfamiliar to him as “the rivers of Russia”. He is far better at remembering cricket scores.

This becomes awkward when “every bastard in the colonies”, from lamb castrators, to shearers, to drovers and their wives, to bushrangers, to housekeepers, shopkeepers and cooks, can recite large chunks of Dickens from memory.

“I have to say, young Dickens,” says local man Willy Suttor on their first meeting, “it’s astounding that you are the closest thing to the great magician himself! The dazzling civiliser of rough men like me!” Plorn bluffs his way through such daily encounters.

This is a bit of authorial invention on Keneally’s part. He read letters between the Dickens siblings, and letters between them and their father. He read books about the Dickens boys and their time in Australia. But whether Plorn had or had not read a word of his father’s at age 17 is not known.

RELATED: The List: authors’ and critics’ best books of 2019 | How to create the perfect bookshelf

Keneally suspects he was dyslexic. “He could write a good letter. You don’t hang around Dickens as a child without picking up a good vocabulary. But it is remarked that he can’t handle text. He couldn’t deal with books.

“So I just presumed he hadn’t — couldn’t — read his father’s books and I thought it was an interesting area of guilt to have. I think he was a lost boy, and that is something I know about. I’ve been in that situation, trying to redeem yourself in the eyes of your parents.”

Yet it’s not just the fact that everyone thinks their father is “God bloody almighty”, as Alfred puts it, it’s also his behaviour at home. While he is able to thrill his children — he and his wife, Catherine, had 10 — with colourful entertainments such as sled rides, when it comes to just being a dad he is a bit of a social distancer.

And at this point, with his youngest child on the cusp of adulthood, Dickens has been separated from his wife for a decade, by his own choosing, and taken up with another woman. He may be a genius, “humanity’s laureate”, as he’s dubbed Down Under, but he’s just a mortal man with human flaws.

“Yes indeed,” Keneally says. “He was just an ordinary, stupid man, who made a f..k-up of a marriage. He was a strange mixture, like many of us.”

The Murrumbidgee oyster moment is also funny, despite — or perhaps because of — its visceral content. And later in the novel, when Plorn finally grabs the chance to lose his virginity, there is a bit of dialogue that is so funny I will not repeat it here. Every reader deserves to read it unsullied for the first time.

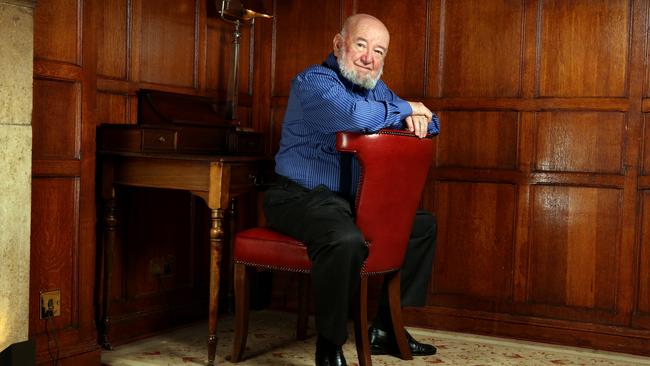

When I tell 84-year-old Keneally that I think The Dickens Boy, set mainly in rural NSW, is his most comic novel yet, he says, “Well, if it is, I’m delighted”.

“And if it is funny I think it’s mainly because I had a bit of a Dickens injection [his research included re-reading all Dickens’s novels]. So he was in my subconscious the whole time and that makes funny things happen.”

His favourite Dickens today? He picks Our Mutual Friend, but can’t put down a full-stop. He adds David Copperfield and Great Expectations.

We’re talking at the apartment Keneally and his wife, Judy, share in the Sydney beachside suburb of Manly, a walk away from the old Quarantine Station and related cemetery at North Head. It’s just before Australia went into pandemic lockdown.

We joke that keeping our distance means we will have to act like Wallaby David Campese did in defence. Then, as we are fair-minded, we note that the glorious goose-stepper remains the highest try scorer in Australian rugby.

When I ask about COVID-19, Keneally, who as a young man trained to be a priest, laughs and goes on a little tirade that encompasses Donald Trump, “fake news” and “ironic gods”.

“The gods are saying, I’ll show you we’re not fake f..king news, mate. This is something you can’t bullshit away with a couple of tweets. We’re back in the era of truth again.”

He seems quite cheerful about it. When I ask Keneally and his wife to name a time in their lives that was more frightening than today, they answer immediately and almost in unison: the fall of Singapore in February 1942.

They were just kids back then, but they knew what it meant: the Japanese were coming. “That was a crisis,” Keneally says.

■ ■ ■

The Dickens Boy is a fast-paced romp through a few years in our colonial history. It ends when Plorn is still a young man, well before his political career in NSW, something that might finally have pleased his father.

There’s a definite sequel to be written, yet Keneally, who in his 80s has an eye on the clock, has already drafted his next novel, about a gay pianist in 1930s Sydney. It is due to come out early next year.

The new novel includes several outright inventions and other circumstances and developments that it’s impossible to know the truth of. Did Plorn meet the bushranger Captain Starlight? He does in the novel and it is a wonderful extended scene. Did one of the brothers who ran the sheep station try to seduce Plorn? Did Plorn chase emus on horseback?

Was Caroline Chisholm to blame for Charles Dickens's abiding interest in Australia, a place to which he was twice invited but never visited? Did the boys hear about their father’s death the way they do in the novel? Almost certainly not.

Keneally does what he does so well: he plucks people from the pages of history and gives them emotional lives.

“You look for the gaps in the letter, the gaps in the journal,” he says. Re-reading Dickens also helped. “When you think about his work, the relationships in the novels as against the relationships in real life, then it’s amazing what will come up. You can get flashes of invention that you never thought you were capable of.”

This opens the door to a question I want to ask at the risk of offending the author’s modesty. Is Tom Keneally Australia’s Dickens? His answer fits the novel. He doesn’t say yes but nor does he say no.

“I’ll tell you what: I’m not as good at frst drafts as he obviously was. His ability to sit down and invent from a standing start was obviously very great.

“He was gifted in that way, and in his capacity to control characters. The way he manages them as they are emerging is phenomenal, and I am aware of that.”

He adds, however, that Dickens was not as good as George Eliot at “ambiguous women”. “He saw marriage as the end of the journey,” he says.

“The most consummate novel of that era is Middlemarch, which has two unhappy marriages in it.”

We will leave the final word to Plornnishmaroontigoonter, to use the full nickname his father bestowed upon him.

“I’m afraid I’m a very ordinary fellow,” he tells people on his arrival. Then, a few pages later, he has one of his first sightings of “this antique and western land”.

I guessed one would call it prairie had it been in America, with glinting outcrops suggestion of gold but generally yielding only quartz. Distant mountains somehow promised infinity, however, rather than any limit.

The Dickens Boy, by Tom Keneally, is published by Vintage (392pp, $32.99).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout