‘Audiences are sick of being told they’re horrible’

The government has been accused of waging a culture war against the arts in this pandemic, but one of the country’s top playwrights says audiences are tired of being ‘beaten over head’ by minority groups.

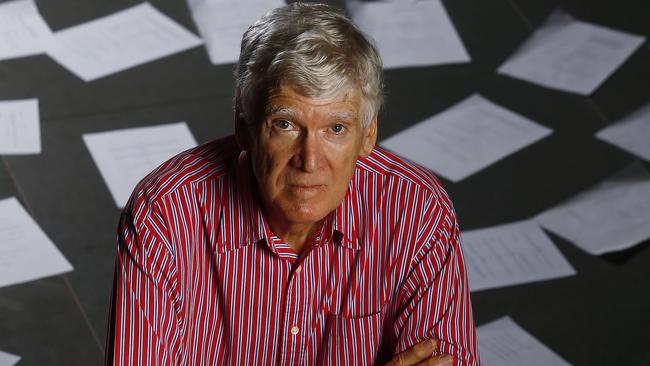

When David Williamson was starting out as a playwright with his satirical dissections of the 1970s in Don’s Party and The Department, Australia’s cultural elites were the people he calls the “first-nighters”. They were from the wealthier suburbs, the silvertails and socialites, effectively being paid by the government to attend premieres at the opera and the ballet.

“We thought they were the real elitists because they were being subsidised about $150 a ticket,” Williamson says.

“The most affluent section of our society was being paid the most to see, to us, elitist art forms. The elitism wasn’t contemporary work. It was the opera and ballet, and I think it still is.”

Today’s culturally privileged are not only the rich but also the poorer citizens who work as actors, comedians, directors, authors, songwriters, filmmakers, painters and curators. They are members of the creative class who hold a mirror to contemporary Australia and tell us what they see. Williamson knows they can rub people the wrong way.

“I do think that some middle-class audiences at the theatre are finding it a little tiresome to get yet another play from yet another minority group, that tells them that they are unconscionable, and beats them about the head, and tells them that they have caused great problems for minority groups,” he says. “I’m sure there is a bit of that. Some sections of the audience are sick of being told they’re horrible.”

A study released this week by Canberra think tank A New Approach also highlights the divide in Australia’s cultural life. The authors wanted to hear what “middle Australians” had to say about the arts, and held focus groups with 56 men and women from the suburbs of Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane and Townsville. The groups comprised swinging voters who worked in offices, trades and other jobs.

In general, they have a very positive attitude about Australian culture, especially activities that inspire the imagination and involve them in their communities. But they showed little interest in the “high arts” that are too expensive, too hard to get to, and not to their taste.

“I am not a big fan of the ballet. I have seen it advertised a lot recently — yeah, not really my thing,” said a man from Brisbane. A Sydney woman told the focus group: “Opera, because of how expensive it is, I don’t think it is easily accessible for everyone. And if you haven’t been exposed to that sort of music you might not enjoy it.”

In recent months, the creative class has taken a great deal of interest in what the rest of Australia thinks. The coronavirus lockdown has devastated the arts and cultural sector, shutting down untold exhibitions and performances and locking thousands out of their livelihoods. Opera Australia, the nation’s biggest and busiest performing arts company, has cancelled 570 performances to date, costing $70m. Losses across the performing arts will likely exceed $540m, not counting screen production, galleries, museums, book publishers and other cultural businesses.

State and local governments have, to varying degrees, held out a lifeline to the arts and culture sector, which will take months if not years to recover. But support from the federal government has been but a blip in total stimulus spending: just $27m for especially vulnerable groups. While Arts Minister Paul Fletcher says “billions” of JobKeeper dollars will flow to those in the arts and creative industries, many are not eligible because they work for government organisations or are employed on short-term contracts. Appeals to broaden the JobKeeper eligibility criteria appear to have fallen on deaf ears.

Just why the arts have been ignored is causing significant anguish and not a little soul-searching. Broadly, the problems can be identified as a failure to effectively communicate the value of the arts; a disconnect between the elite arts and the general community’s idea of culture; and a difference in values between the progressive creative class and the conservative government.

Arts and culture are big business in Australia when you include film and television drama, publishing, live and recorded music, galleries, museums, dance and drama teachers, the professional performing arts and other activities. The government’s Bureau of Communications and Arts Research puts the value of cultural and creative activity at $111.7bn a year, although that figure includes creative industries such as fashion, media and information technology.

Taken alone, the creative arts contribute $14.7bn to the economy and employ 193,000 people, according to the Australian Bureau of Statistics. As an employer, the arts is bigger than finance, accommodation and coalmining, but many people don’t recognise its significance. In a report released this week, the Australia Institute found that 68 per cent of people underestimate the size of the creative workforce compared with coalmining. It’s an indication, says research director Rod Campbell, that people don’t recognise art and culture as an economically dynamic industry and one that employs tens of thousands of Australians.

A second challenge for the arts is to shake off the elitist tag and connect meaningfully with people beyond a rusted-on audience. One approach has been to widen the frame of reference by giving a boost to artists from different cultural backgrounds.

This is the policy of the federal government’s arts agency, the Australia Council. Its corporate plan sets out strategies to increase the visibility of people from cultural minorities, with particular emphasis on celebrating indigenous artists.

The intention is to give fuller expression to the many different voices and perspectives that make up our nation. One of the findings of the New Approach study is that people value those diverse cultural experiences. But a constant emphasis on minorities or identity politics also risks alienating the mainstream, leading to those familiar accusations of cultural elitism and political correctness.

“Very good at preaching to the converted, not so good at talking to nonbelievers,” is theatre director Sam Strong’s diagnosis of the malaise in the arts sector. But he believes that art is also the way to reach across the cultural divide. Strong recently directed Williamson’s Emerald City — the season at Melbourne Theatre Company was cut short by the lockdown — and is due to direct the stage premiere of Trent Dalton’s Boy Swallows Universe, now scheduled for next year.

“That is a great example of a contemporary Australian story that has engaged vast numbers of people,” Strong says of Dalton’s novel. “I think that’s partly because there’s an immediacy to Trent’s writing and a lack of pretension. But ultimately there’s a capacity for people to recognise themselves and their own experience in those stories.”

The divide between the arts sector and the rest of society is perhaps more imagined than real, Strong says. But the question remains why the federal government has stayed silent on a substantive rescue package for the sector, and the implicit message is that “what we do isn’t valued”.

Strong is careful not to blame the lack of federal support on an ideological stand-off with the Coalition, believing the sector has to own its own failures. But others do. This month actress Noni Hazlehurst accused the government of “waging a culture war” against the arts by denying industry assistance. And Williamson says conservative governments have long regarded the contemporary arts with suspicion, seeing in a film’s or a play’s social critique an attack on their own kind.

“Conservative governments are quite happy with anything that was written 200 years ago — the opera and the ballet — that’s not threatening,” he says. “But I do think there is an element of conservative governments feeling threatened by contemporary work and, consciously or unconsciously, that’s part of the reason they don’t value and don’t fund the arts.”

Indeed, the Coalition’s relationship with the arts has been less than rosy in recent years. There are bitter memories of budget cuts in 2014 and of former arts minister George Brandis’s radical intervention in arts funding. Coalition funding for the Australia Council remains less than that of the last Labor government. And funding for the arts across all tiers of government is in decline. An earlier study by A New Approach reported a decrease of 4.9 per cent in Australian governments’ arts spending, in per capita terms, in the decade to 2018.

Esther Anatolitis, of advocacy group National Association for the Visual Arts, says what is apparent, more than any culture war, is simply a lack of interest from Canberra in a large part of Australia’s economic and cultural life.

“The fact that the government has failed to respond with a specific stimulus is the clearest demonstration that they just don’t want to,” she says. “The government talks about throwing out ideology … but in practice they are being driven by a set of values, and one of those values is not to support the arts.”

Leaders in the arts sector say they must continue to make the case for investment in an industry that brings economic and other pay-offs: that the arts assist schoolchildren in their learning and concentration, that a strong cultural life aids social cohesion and national identity, that creative activity can help ward off some effects of old age.

But there is also a need to master the politics of persuasion, to read the community’s mood, to break out of the arts bubble and to change the well-entrenched narrative that the arts are elitist or only for the rich.

At the time of coronavirus and the nation’s emergence from hibernation, the stakes have never been higher.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout