The hard plot to kill Margaret Thatcher

A new book examines the 1984 IRA plot to kill Margaret Thatcher, the wounds still tender to touch in parts of Northern Ireland.

On a recent podcast, former Sinn Fein leader Gerry Adams was asked what would have happened if the 1984 bombing of the Grand Hotel in Brighton had found its target, and Margaret Thatcher had been killed.

“There would be very few tears shed for Margaret Thatcher in republican Ireland, or in many villages in Wales and working-class Scotland and England itself,” he replied.

The podcast hosts – former Tony Blair spin doctor Alistair Campbell and former conservative MP Rory Stewart – then asked Adams if he would have been happy if Thatcher had died.

“Happiness or happy is not a term I would use,” he replied. “The fact is, there was a war. Margaret Thatcher was notorious, presiding over the deaths of the hunger strikers, which could have been easily resolved by very simple improvements in the prison regime … She was being the Iron Lady, masquerading as being somebody who was indomitable, and so on.

“But, it’s done, it’s over, it’s gone. All of that was in the past.”

It is not, in fact, so far in the past, with the wounds still tender to touch in parts of Northern Ireland.

In Belfast today, the Troubles are a tourism experience. Taxi loads of visitors are driven up the infamous Falls Road by studiously apolitical drivers to gawk at the barbed wire, and the political murals on the high brick walls. British police aren’t welcome, hunger striker Bobby Sands and the 10 who died with him are not forgotten, the innocents murdered by loyalists are still mourned. Justice and independence demanded.

The cars then swing up the Shankhill Road where the loyalist communities proclaim their allegiances with Union Jack bunting strung across the streets. A series of murals express anger over the Good Friday Agreement release of “murderers”. Civilian dead are memorialised and mourned, a tombstone refers to their “slaughter” and a sign lists among the IRA’s sins “rape”, “child abuse”, “mayhem”, “mass murder” and “mutilation”.

At night, the cross roads are sealed to ensure both communities sleep in relative peace. Neither side is ready to pull down the wall just yet. There is still much to be written, and read, starting perhaps with a new book by the Dublin-based Guardian correspondent Rory Carroll, who has just published Killing Thatcher, an account of the IRA’s audacious Brighton hotel bombing.

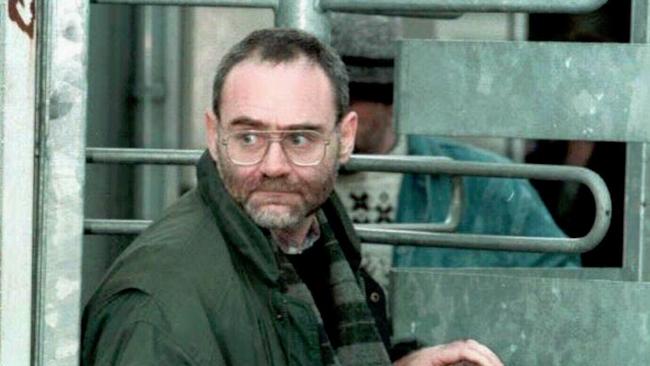

It is a step-by-step recreation of how and why the republican soldier Patrick Magee checked into a room on the premises in September 1984 and set a timer to explode during the night before the start of the Conservative Party’s annual conference.

The bomb was placed to ensure a five-ton chimney stack would crash through the front rooms where the IRA knew Thatcher would be staying, and while it crashed through a bathroom which she had only recently vacated, the PM and her husband survived.

Five others weren’t so lucky.

Over Sunday morning coffee in a seaside town south of Dublin, Carroll says he was not surprised by – nor does he disagree with – Adams’s assessment of the Thatcher counterfactual.

“Adams was right … few in Ireland would have wept over Thatcher after the hunger strikes. She became so hated, not just by republicans but even among middle class people who did not support the IRA.”

Carroll’s book also considers a failed attempt on Adams’s life in Belfast traffic, just six months before the Brighton bombing. Loyalist assassins fired 20 shots at the republican leader’s car. He survived wounds to the neck, shoulder and arm.

“Beyond republican circles, few wept for Adams’s wounds,” he writes.

The journalist, whose career began in Belfast but has included stints as a correspondent in Africa, Latin America and Iraq – he was once abducted in Baghdad at a time beheadings were in vogue – says he was motivated to write about the Grand Hotel bombing because it was in danger of becoming part of a collective forgetting.

“The Troubles went on so long, there were so may attacks, atrocities, incidents, that’s all melded into each other for those who lived through them; and when they largely ended, I think there was a collective desire to turn the page, which is very understandable,” he says.

“When it came to Brighton, I just thought the event was so important and it was so largely untold … I realised that there is so much about the Brighton attack that I thought I knew but it turned out that I’d never really known it, or if I had known, I’d forgotten it.”

Thatcher contributed to the forgetting of the incident by dusting herself off, and insisting the conference go ahead. Carroll says a fleet of buses was hired so Conservative members who had escaped in their nightclothes could be taken to a nearby Marks & Spencer store so the show could go on. The Iron Lady scoffed at the heavy security provided to her at the rear entrance of the hotel, and swept through what was left of the front door to give a rousing speech.

“The IRA not only failed to kill her, they also failed to disrupt the conference,” Carroll observes. “She (Thatcher) was of the Blitz generation and this was the stiff upper lip of not dwelling on your sufferings or traumas or even acknowledging them.

“I was talking the other day to Nadine Dorries, the ex-culture minister of the Tory party, and she was telling me that within her circle of Tories, even people who were in the hotel that night they simply do not talk about it, not even to reminisce.

“That was why the story of what happened had been largely untold.”

Carroll’s account of the central characters, including the forensics and bomb experts whose work led to Magee’s identification, is excellent (Magee, having been released with all the other political prisoners as part of the Good Friday agreement, is reportedly a familiar sight on the Falls Road but keeps a low profile). His telling of the 1979 assassination of Lord Mountbatten in the picturesque port of Mullaghmore is a chilling scene-setter, and the second-by-second countdown to the bombing is unforgettable. It is a balanced account – yet the author claims no “moral neutrality”.

“Not in a story of murder, people being blown out of their beds,” he says. “What I tried to do to (is) let the key characters, including the IRA ones - or especially the IRA ones - (explain) for the readers why they did what they did, why the IRA considered this justified,” he says.

“Some readers may concur and say ‘it was such asymmetrical warfare when you are fighting the might of a modern nation state with a couple of hundred working class guys taking on the might of MI5, MI6, Scotland Yard etc, how else are you going to do it? I wanted readers to understand that without slipping into exculpating or cheerleading what the IRA did.”

Peter Lalor is an Australian writer whose books include Blood Stain and The Bridge.

Killing Thatcher

HarperCollins, Nonfiction

416pp, $32

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout