The golden age for wandering artists shines bright in this exhibition

Paul Jacoulet was born in an exotic location and made his life there, while Ian Fairweather fled in search of the exotic.

Many artists in the course of history have been birds of passage, migrating from one country or city to another, seeking the epicentres of energy and artistic dynamism. Around 1600, the centre was Rome, and so many young men settled there from other parts of Italy or Europe that they were regularly nicknamed after their city or country of origin, like Caravaggio, the second painter named after this small town south of Bergamo, following the High Renaissance painter Polidoro da Caravaggio. Other famous examples include Claude Lorrain and Valentin de Boulogne.

In the late 19th century the centre of modern art moved to Paris and from then until the period between the world wars the city was overrun with painters, not only from all over Europe but also from the US, Australia and as far away as Japan. That cosmopolitan aesthetic culture is still the background to the 1951 film An American in Paris, although by then the centre had moved again, this time for a couple of generations, to New York.

Artists also can move because their talents are inherently portable; when in the 1660s Jean-Baptist Colbert tried to force Pierre Mignard to join the newly founded Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, run by Mignard’s rival Charles le Brun, the artist is said to have held up his hand and declared that with these five fingers he could make more money in any country in Europe if he chose to leave.

A few artists travelled farther afield in the early modern period, such as Gentile Bellini who went to Constantinople to paint the portrait of Mehmet II (1480, National Gallery London), and it would be fascinating to know more about artistic exchanges between the Persian and Chinese cultural worlds, especially after the Mongol conquest in the 13th century.

In the 18th century Jesuit brother Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) became a court painter to the Qing dynasty emperors, took the Chinese name Lang Shining and developed a unique hybrid style combining Western and Chinese elements.

From the 18th century the development of the Grand Tour as a rite of passage for members of the upper classes (and increasingly the upper middle classes) led to a demand for paintings of the famous cities and other sites visited, including Venice, Rome and Naples, later extending to Sicily, then later still to Greece. Much of this appetite for souvenir paintings was satisfied initially by local artists, but northern painters increasingly travelled to the same places, especially as Rome and Naples were already traditional centres for what we might now call postgraduate training. The Napoleonic adventures in Egypt and later the French conquest of Algiers in 1830 extended the field of artistic travel in the Mediterranean; Eugene Delacroix painted the celebrated Femmes d’Alger in 1833.

By this time, however, far wider horizons were opening to migratory artists as the great age of European discovery and exploration, from the 16th to the 18th centuries, turned into an age of colonial expansion. Now it was no longer small numbers of Grand Tourists who travelled around the Mediterranean or bold adventurers who ventured farther afield but tens of thousands of ordinary people who went off to make a new life in remote lands. These new communities eventually wanted images of their own experience, while those who had remained at home were also curious about the lands to which their relatives had moved.

Many of the early artists of Australia were travellers. John Glover had been on the Grand Tour circuit before settling in Hobart at the age of 64; even earlier, Augustus Earle, who was in Sydney for only a couple of years (1825-27), was an inveterate traveller who went on to India before joining Charles Darwin on HMS Beagle (1831); Conrad Martens succeeded him on the Beagle and then settled in Sydney. Eugene von Guerard trained in Rome and Naples before coming to Melbourne, and later retired to London, while Louis Buvelot, from Switzerland, worked for years in Brazil before migrating to Melbourne.

Perhaps the final phase of the migratory bird artist comes in the later 19th and first half of the 20th centuries, when steamships and eventually aeroplanes made it easier to visit remote places for shorter periods, and yet when the whole world had not yet been reduced to the relative consumer homogenisation that has rapidly spread since World War II and in particular in the past half century. When my father explored Cyprus on a motorbike in 1948, for example, much of the country, and the lives and dress of the people, had barely changed since the 18th or 19th centuries; today, and I have been there several times in the past decade, the daily lives, dress and habits of the ordinary people are almost identical to those of populations anywhere in the world.

The period between the mid-19th and the mid-20th centuries was thus a time when it became increasingly easy to visit distant and exotic places, but when local cultures were still relatively intact and vital. It was a kind of golden age for wandering artists, from Paul Gauguin, the most famous, to Ian Fairweather (an adopted Australian of Scottish birth) or Paul Jacoulet, the two subjects of an interesting exhibition, or rather pair of exhibitions, Birds of Passage, at the Queensland Art Gallery.

The story of Jacoulet (1896-1960) is particularly fascinating and no doubt will be new to most readers. He was born in France but from the age of three grew up in Japan, where his father was a professor of French. This was in the extraordinary vital time of Japan’s rapid modernisation during the Meiji period (1868-1912), but when only a handful of foreigners lived in the country. Young Paul attended a Japanese school with local boys of his age and became fluent in the language, as well as several others. The family’s next-door neighbour was a famous artist of the later ukiyo-e style and it was from him that Paul began to learn this traditional art form, whose greatest period had been between the late 18th and the mid 19th centuries but was trying to reinvent itself for the modern age. By 1933 he had set up his own printmaking studio in collaboration, as was conventional, with a block-cutting specialist and a master printer.

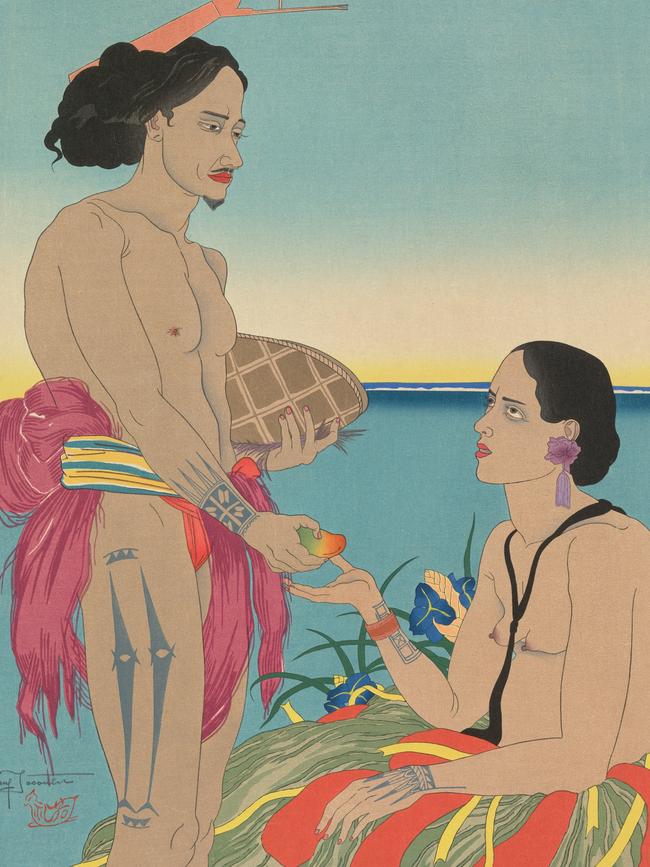

Despite his deep connections with Japan, a relatively small proportion of Jacoulet’s work is devoted to Japanese subjects. Much of his inspiration came from visits to the islands of Micronesia which, since World War I, had been a Japanese protectorate. It was thus easy for him to make repeated trips to the Marshall, Caroline and Mariana islands; he took an interest in the traditional life and customs of the local people, even though by now these lives had been reshaped by successive colonial influences, first German and more recently Japanese – and indeed Jacoulet himself would picture them through a traditional Japanese artistic language.

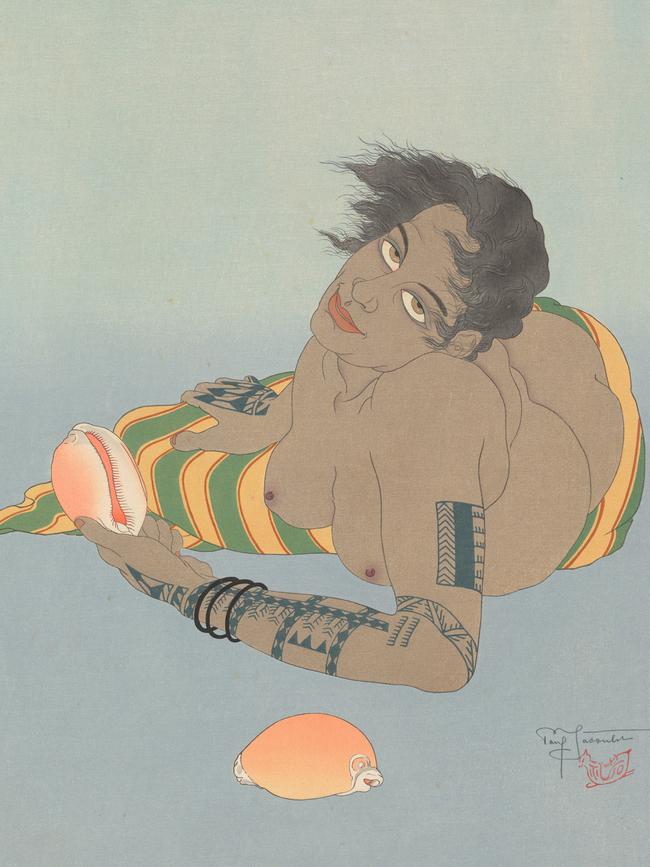

In general, he conceived of these pictures as a modern interpretation of the traditional ukiyo-e portraits of famous beauties and courtesans, with refined outlines, flat areas of colour and bright pigments. Jacoulet was homosexual, but this is only indirectly apparent in the preciousness of his art, and perhaps paradoxically in his concentration on the feminine. Only one work is overtly erotic, and that is the image of a reclining woman looking at the viewer with a knowing expression and slightly hooded eyes; even though she has bare breasts and holds a shell that is a vulval symbol, it is tempting to imagine that this work, which hung over his bed for many years, might have started as the face of a youth. \

The story of Fairweather (1891-1974) is far better known in Australia. Born in Scotland but raised by elderly aunts, he did not see his parents or his siblings, who lived in India, until the age of 10 and always remained at heart a loner. He joined the army and was captured in France on the first day of World War I, spending the remainder of the war as a POW in Holland, taking the opportunity to learn to draw and study art history and the Japanese and Chinese languages. After the war he studied art at the Slade School in London (1920-24), and the exhibition includes several fine early drawings that demonstrate his feeling for figure drawing and especially for the dynamics of movement.

Unlike Jacoulet, who was born in an exotic location and made his life there, Fairweather fled in search of the exotic. He exemplified the spirit of Charles Baudelaire’s poems about travel, which evoke an instinctive urge to escape, to seek something not fully understood in unknown lands. But instead of dreaming of a great voyage from the safety of a Parisian cafe, Fairweather actually set out, in 1928, on what turned into decades of restless wandering around the Far East, from China to Bali and The Philippines, before finally settling on Bribie Island, off the coast of Queensland, after a final, nearly fatal raft voyage in 1952.

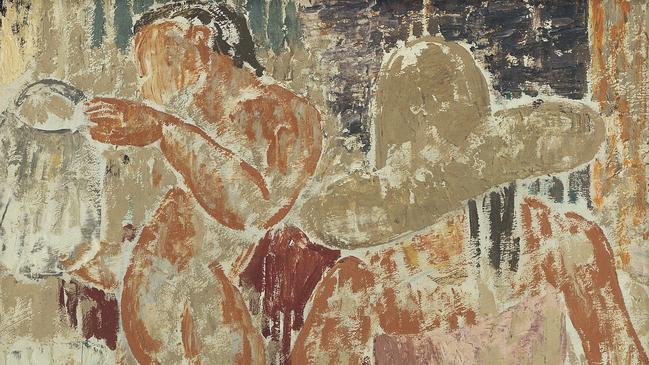

Fairweather was undoubtedly drawn to the simplicity and authenticity of the people among whom he lived – frequenting the humble, still living in a manner almost untouched by history, rather than those of his own class, who were already relatively Westernised. And unlike Jacoulet again, he was less drawn to painting individuals than groups of figures engaged in collective activities.

His subjects were things seen momentarily but that struck him as having a kind of emblematic significance and that he often returned to later from memory. It was his Slade training that allowed him to capture the vital movement of individual figures and groups so economically, as we can see in the figures of the young men gathered around a cockfight, or again in the standing torso of a boy, both scenes of peasant life in The Philippines.

There are hints of the erotic here, too, as there will inevitably be in any representation of the human figure, but they are even more elusive than in Jacoulet’s work, and there is little evidence of any intimate personal relationship in Fairweather’s life. His work expresses a different aspiration, to a kind of impersonal transcendence, as we see in the complex works of his maturity in which figures are entangled and overlaid with quasi-abstract patterning.

These compositions evoke an impression of collective or communal unity, as in the largest painting in this exhibition, Kite Flying, painted in 1958 but typically based on memories of his period in China a couple of decades earlier; yet, as with the crowd watching the cockfighters, of which he could only be a spectator, this was an ideal that remained inaccessible to an essentially lonely man. The Baudelairian voyage of escape is as much an evasion from society as anything else, and its destination may prove in the end to be solitude.

Birds of Passage

Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Museum of Art, Brisbane, to January 26

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout