Von Guerard: Artist-Traveller at Ballarat Art Gallery

Dismissed by Robert Hughes in 1966, artist Eugene von Guerard is now seen as one of our most important artists.

It is surprising how many people cling to the myth that artists are not properly recognised until after their deaths. To a practitioner, such a belief can be a frustration and a consolation of last resort. To the layman, it confirms their perception of art as a thankless career. The evidence for this prejudice is scanty: most people think of van Gogh, a bad example as his best paintings were produced in a couple of short years before his death. They forget all those who, from Titian to Picasso, enjoyed great success in their own lifetimes.

More curious are the cases of artists who were recognised in their own time but forgotten or depreciated afterwards. They are exceptions among the artists we generally consider important, but interesting exceptions: Botticelli and Vermeer are among the most prominent of those who were nearly completely forgotten for a time, but their invisibility can be explained: Vermeer painted three dozen pictures in one city and many for one patron; his art never achieved a wider reach or influence in its own time. And Botticelli was working in a style that seemed archaic and grew increasingly unfashionable in his lifetime.

The decisive factor seems to be whether an artist was accepted into the canon during their lifetime and in the period immediately afterwards, when the admiration and emulation of the following generation confirm their status. For different reasons, neither Vermeer nor Botticelli was properly canonised at the time, and this made it easier for them to be fall into relative oblivion.

Similarly, artists who enjoy great commercial success and even prestige in their lifetimes may be rejected by the following generation, as occurred with many of the academic painters of the late 19th century and less conspicuously with various modernist artists in the 20th.

Eugene von Guerard, it is now clear, was one of the most important artists of Australia in the 19th century, yet he almost disappeared from view for a century or more. By the 1960s he was all but ignored even by the doyen of Australian art history, Bernard Smith, barely mentioned in the first edition of Alan McCulloch’s Encyclopedia of Australian Art (1968) and dismissed by Robert Hughes in his youthful The Art of Australia (1966). In the past quarter of a century he was rediscovered by scholars including Tim Bonyhady and became a reference point for Australia’s leading postmodernist painter, Imants Tillers. He was fully restored to the position of artist of the first rank in Ruth Pullin’s 2011 exhibition Eugene von Guerard: Nature Revealed, at the National Gallery of Victoria.

Von Guerard’s case represents a colonial variation on the model I have suggested. He was generally highly regarded, but the public of his time and place, in the still new city of Melbourne, consisted of a limited number of competent people. And there was, as yet, nothing like a canon of Australian art.

Unluckily for von Guerard, that canon was founded on the work of the successors who eclipsed him, the painters of the Heidelberg group. And the only earlier artist the Heidelberg painters admitted as a precursor was Abram Louis Buvelot, a painter in the Barbizon style whose more informal style had already started to draw public favour away from von Guerard at the height of his career.

In the myth of the Australian school that was elaborated in the early 20th century, the Heidelberg painters had been the first to see the natural environment of this country, particularly its light and its flora, with fresh eyes, while their precursors had imported European habits of painting. The true Australian painter was intimately connected to this land, while the colonial artist was a rootless wanderer. Von Guerard came to personify everything that could disqualify an artist as a member of the Australian canon: he was foreign, cosmopolitan and academic.

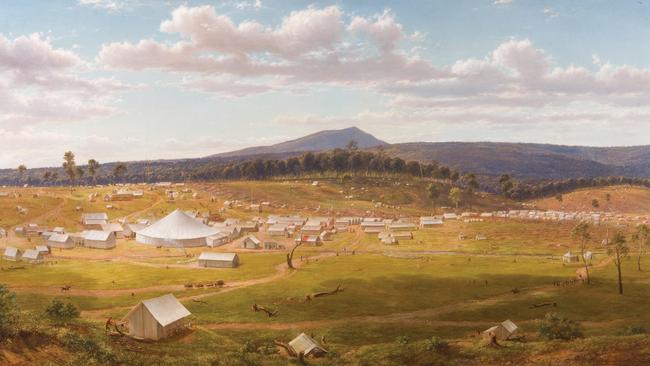

But that is precisely why, in this outstanding new exhibition, Pullin has chosen to focus on von Guerard’s role as a travelling artist, as indeed an artist explorer. He was not at all, as it used to be carelessly assumed, a painter who came here with a set of preconceptions and did little but repeat familiar routines. On the contrary, he approached the Australian environment with an unmatched curiosity, care and precision of observation.

Von Guerard was born in Vienna, where his father was already a court painter. They spent 12 years together in Italy, six in Naples — where his father died in 1836 — itself a singularly active centre of artistic and cultural exchange.

This Ancient Greek city, which had continued to prosper even after the fall of the Roman Empire, had later been a centre of the baroque, and then an indispensable destination on the grand tour, especially since the explosion of modern archeology in the second half of the 18th century with the excavation of Pompeii and Herculaneum; the transfer of the Farnese collection of antiquities from Rome, meanwhile, formed the core of the great National Archeological Museum. The city had been home to many remarkable people, including William Hamilton, the British antiquarian and vulcanologist, and some of the most important artists resident in Naples, such as Johann Philipp Hackert, had long been German.

When von Guerard came to Australia, attracted by the gold rush that fuelled the spectacular growth of Melbourne, he found himself once again in such an expatriate community. Almost all the leading intellectuals and scientists of Melbourne were German, and this milieu undoubtedly reinforced his interest in the ideas of the great German naturalist Alexander von Humboldt, who was a younger friend and intellectual heir to Goethe — not to be confused with his equally brilliant older brother, Wilhelm von Humboldt, one of the foremost linguists of his time.

Surrounded by a remarkable group of scientists, and in a city in which there were few artists of comparable ability — Nicholas Chevalier became a friend but, though brilliant, never had von Guerard’s depth and seriousness — it was natural for von Guerard to conceive of his artistic vocation, in a profoundly Humboldtian spirit, as part of a great scientific project of understanding the natural environment, especially the environment of a new world that had never been studied before.

Thus, having already travelled as far as Australia, he also travelled widely around Victoria, and took part in two of the 10 magnetic surveys of Victoria undertaken by Georg von Neumayer. One of these was to Cape Otway — annotations in German in his notebooks suggest the party were speaking their own language on this journey — and the other to Mount Kosciuszko, where he painted what is perhaps his most famous landscape and the greatest expression of the Australian sublime.

In all these landscapes, however, we can see von Guerard bringing an extraordinarily intense and geologically informed eye to bear on the new landscapes. If we compare these pictures with the few early works from Italy that are included in this exhibition, we can see how much harder it was to paint in Australia, but also how these challenges sharpened his understanding of geology. In Italy, the country is endlessly varied and picturesque, and everywhere architecture — ancient or modern, intact or in ruins — blends harmoniously with nature.

In Australia, the land is flat and often dull, and there is no architecture, for nothing had been built. It was all the more essential to understand the natural morphology of the land, and we can see von Guerard had not just an eye for detail but a feeling for the whole character, one could almost say the physiognomy, of certain geological forms. He also had the patience and insight to elicit shape and pattern from what to an untrained eye could seem a chaos of scrappy vegetation in a featureless topography.

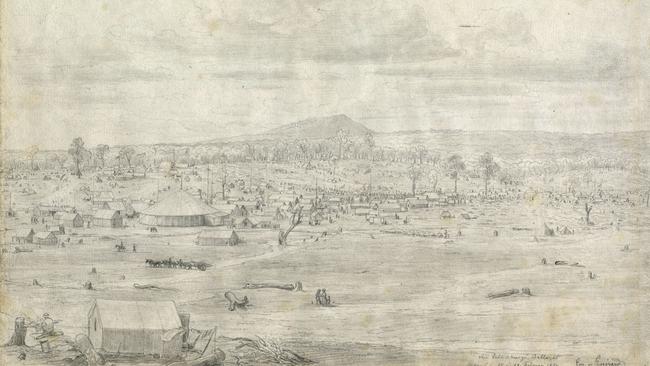

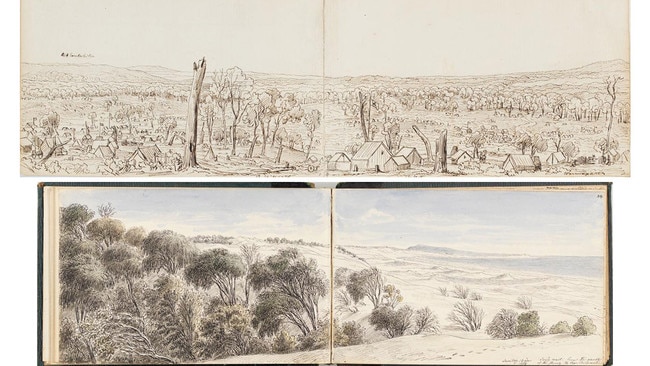

And this is why the artist’s notebooks are so important and beautiful. Indeed, although this exhibition also includes many less familiar paintings, including some from private collections that most of us will never have seen before, it is the sketchbooks that particularly reveal von Guerard’s process and way of thinking. And the publication that accompanies the exhibition, The Artist as Traveller: The Sketchbooks of Eugene von Guerard, is one of the most scholarly and beautiful books produced on Australian art history.

For although the late 18th and early 19th centuries were the period when plein-air painting began to flourish, first in Rome, then, through the work of artists such as Camille Corot, in France and the north as well, von Guerard preferred to draw in the field and paint in the studio. This approach was in fact indispensable if he was to achieve structural precision in the delineation of geological forms, but it compounded his fall from grace with the following generation, which preferred the painterly unity in the handling of light and colour that comes from working from the motif, to the accuracy of form that arises from a much longer and more careful preparatory drawing.

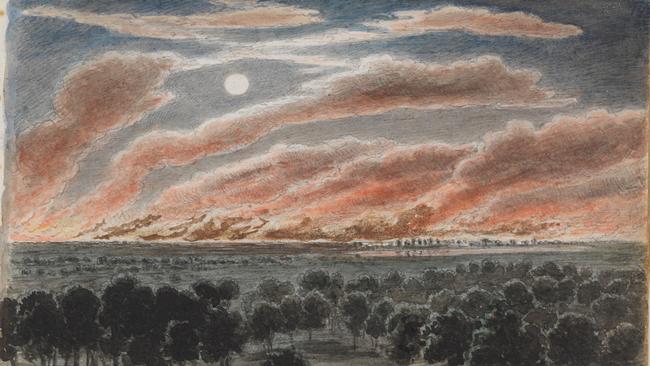

But this is not to say that every one of von Guerard’s drawings is minutely detailed and mechanically exact. In fact they vary considerably, from quick sketches that capture the main features of a scene to exquisitely accurate studies. There are several beautiful drawings in which the central parts of the composition are drawn with the finest discrimination, while other sections that limitations of time prevented being fully resolved are summarily sketched in. And there is one small but evocative drawing that, even from a distance, catches the eye with a Corot-like quality that is unusual for von Guerard but explained by the fact it was done from memory.

Even his finished paintings, although sometimes executed many years after the preparatory drawings, have a sophisticated sense of lighting and mood, as if he could recall effects seen long before. For these sketchbooks are, as the curator points out and indeed as every artist knows, like visual diaries. Writers may expatiate on feelings and ideas; artists fill sketchbooks with drawings that crystallise their own particular form of thinking.

Von Guerard’s sketchbooks also remind us of something that we may all have noticed with travel diaries in particular. It is far less useful to fill pages with purple prose about how we felt at a wonderful natural or archeological site than to record that a beggar tried to sell us a pair of scissors or a dog ran off with our hat or that we had lunch at a shabby but friendly bar on the roadside: for these simple facts will serve as cues to recover and distinguish the memories of that particular day. In the same way, von Guerard’s dispassionate and exacting records were keys to a world of feelings and associations that he could conjure up anew when he transformed these drawings into paintings.

Eugene von Guerard: Artist-Traveller

Ballarat Art Gallery, Ballarat, Victoria, to May 27.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout