The day faith got stuck in the chimney

Christmas is a vault in the memory that creaks open in December. It’s a time for keeping the faith... in the future, the past and in Santa Claus himself, writes former political adviser Don Watson | WATCH

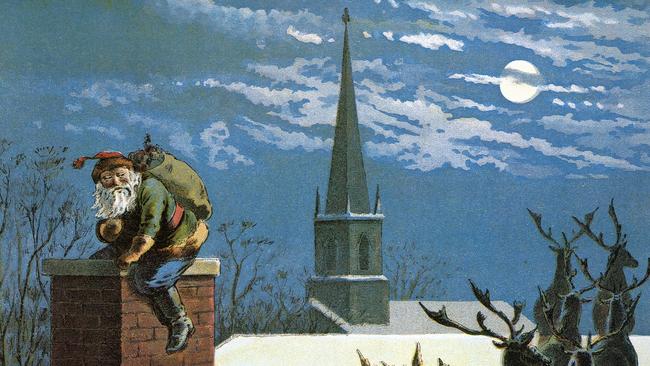

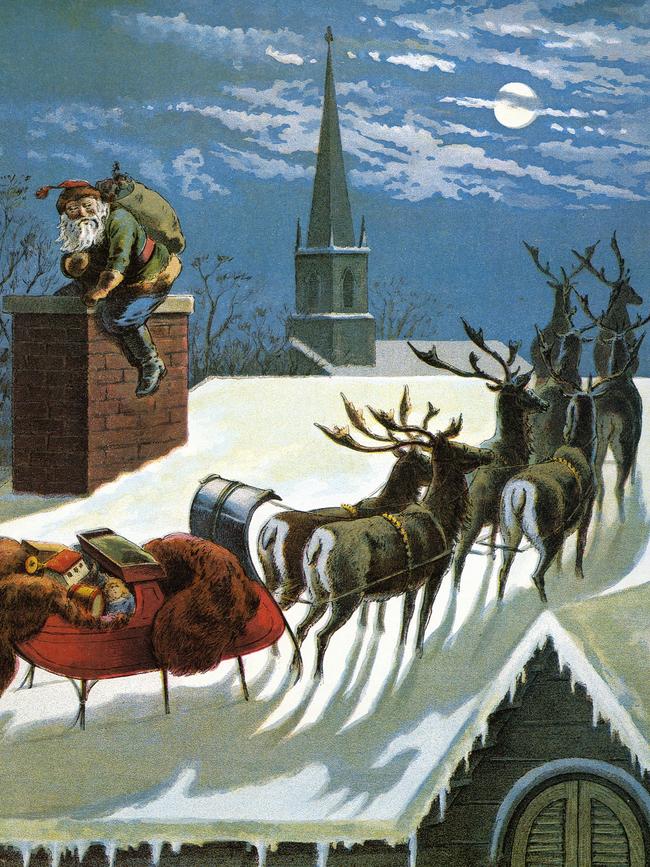

The first Christmas I recall was an unseasonably cold one. My father rose before dawn to get a fire going, but the fire wouldn’t draw because Santa Claus was stuck in the chimney. Dad tried to prise him out with the handle of the broom, but Santa bellowed like a bull, which was distressing for everyone, so Mum put a cushion on the end of the broom and, with all his considerable strength, my father tried to push him out the top. When that failed to budge him, he got the ladder and climbed on to the roof with a rope. There were snow flurries up there, and the dogs were barking, probably at the reindeer standing on the cowshed.

My father dropped a rope down the chimney, but Santa’s arms must have been pinned tight because he didn’t grasp it. Dad came down and said the silly bugger must have got the bag jammed in beside him. You’d think he’d have more sense. But that was just our luck – millions of chimneys and he gets stuck in ours. There was a blight on the family, Dad said. “But what are we going to do?” my mother asked. “We can’t just leave him there to rot.” “What do you suggest?” Dad said. “I’m not going to pull the chimney down, if that’s what you’re thinking!” My brother began to cry and shout: “You can’t pull the chimbley down! Not the chimbley!”

I don’t know how he got out, but when we kids woke up, the fire was going and I had a new trike. Blue, it was. I rode it around in the gravel all morning and most of the afternoon, but then my brother backed over it with the tractor, and blamed me for leaving it where he couldn’t see it. I remembered the disaster when I woke the next morning and sobbed bitterly. But when I went outside there it was, just as I had left it, parked behind the tractor. I began to read the New Testament every night.

Santa got stuck again the following year, and the year after that. The last one was the worst. Dad tried to pull him out with a baling hook he had bound to the end of the broom, but he only succeeded in pulling down a big black boot with Santa’s foot and lower leg in it. “That’s funny,” said Dad. “Does not a Father Christmas bleed?”, which did not sound like him, and he looked very surprised by the phrasing, and then torrents of blood and viscera spilled into the fireplace and Mum screamed: “Don’t let it get on the carpet!” And her mother, who lived with us, said: “They’ll be here soon, and you won’t have the turkey on.”

That year my brother and I were given a hydraulic-powered rocket ship between us. My brother being older had first go. He put the water in it and operated the lever according to the instructions on the box. Then he set it on top of a post, pressed “Fire” and leapt back as if he thought he would be scorched. The rocket went fifteen feet into the air and fell into the sheep dip. We retrieved it with a stick, but it never worked again. My Christmas was as good as over by 8am. I might have called out, “why persecuteth thou me?” but I was only up to St Luke where it said things that are impossible with men are possible with God. I began praying on and off every day.

My faith in Santa Claus was shaken by the rocket ship but I wanted a portable radio to listen to the races, so I took Pascal’s wager and laid off on Jesus – a boxed quinella, if you like. No longer trusting Santa to deliver, I pleaded with my parents to render unto their third born a little Bakelite model in the local electrical store for six pounds 19 and sixpence. My father said if I wanted one so badly, he would pay me threepence an hour to cut thistles until I had enough to pay for it, then I could give it to myself for Christmas. I hacked away at the thistles for two hours, which took care of the sixpence. Truly, I never wanted anything more than I wanted that radio, but another 556 hours meant I couldn’t get it by next Christmas unless I left school. And I was only eight. I gave up. That year they gave me a reading lamp, which speeded up the New Testament.

By now I was up to Revelation and the bit about grasshoppers as big as horses with hair like that of women and their teeth “as the teeth of lions”, and I was at last getting really involved. But when, next Christmas, I got colouring pencils and Jesus the Boy, and colouring pencils again the next year, my faith fell away completely.

Christmas Day evolved into a familiar pattern. A little of Handel’s Messiah on the radiogram until our impious relatives arrived. Then we learned to grin as sweetly as we could while balding uncles called us by our brothers’ names, and aunts with the teeth of lions looked us up and down to see which if any of our relations we resembled and what sort of specimens we were in general. There was one whose first words were always: “Can you spell ornithyrincus?” One year I said “No, but I can spell ‘platypus’, which is the same thing”. That fixed her.

I came to quite like Christmas and still do, not least for the curious sensation of finding oneself playing the same roles, and uttering the same words, as the adults had all those years ago. Christmas has a mnemonic function. It is a vault in the memory that creaks open in December and allows us to regain the voices and sensations of our childhood still floating there. I came to think the panic and shame of Santa’s entrapments in our chimney seemed to be a lesson in the vanity of human wishes; but more recently an analyst seized on it as the key to the problem for which I had consulted her – writer’s block.

Don Watson, 73, is a profound and beautiful writer of non-fiction books, essays, cultural commentary, feature films and speeches. One-time speechwriter for prime minister Paul Keating, his books include a history of Australia for young readers, and a glorious ode to the Australian landscape, The Bush, which won Book of the Year in the NSW Premier’s Literary Awards in 2015.An account of his travels in the United States, American Journeys, was awarded The Age Book of the Year and won the Walkley Book Award, and Recollection of a Bleeding Heart, about his time working for Keating, won the National Biography Award. His book Death Sentence, about the decay of public language, won the Australian Booksellers Association Book of the Year in 2008. The seeds of his latest book, The Passion of Private White(Simon & Schuster), were planted when he met anthropologist, Neville White, when both men were undergraduates at La Trobe University in 1968. White, a conscripted veteran of the Vietnam war, spent more than five decades studying two Yolngu clans in remote North East Arnhem Land.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout