The Adelaide Biennial offers intriguing contemporary and Australian works

The Adelaide Biennial’s Inner Sanctum supports contemporary and Australian art, and the power of painting that transforms the experiential world into visual meaning.

The title of a book is meant to give readers some idea of its content, but those of contemporary art exhibitions are usually completely fanciful. Perhaps this is inevitable given they are meant to cover a disparate collection of works and are often chosen before the works themselves.

But perhaps most annoying is to find the same old jumble, all too often, advertised under a new label each time. And when the curators try to explain themselves in a sort of manifesto for the exhibition they propose, it becomes even sillier, as we saw a couple of weeks ago with the Sydney Biennale.

At least the title of the Adelaide Biennial is not as ludicrous as the Sydney Biennale’s hyperbolic Ten Thousand Suns, but even “Inner Sanctum” raises questions, and makes us ponder how loose and imprecise the language of the art world has been for many years. Do they mean that art serves us an inner sanctum in general? Or that it plays that role today? Or that the art they have chosen is uniquely suited to this purpose?

The expression seems to be understood as something like a synonym of “sanctuary”, in the sense of a place where we can take refuge or seek shelter. The two words come from the same Latin root, meaning originally holy, devoted to the gods or taboo. A sanctuary was originally a place devoted to the gods but, because suppliants would seek refuge in such places, putting themselves under the protection of the divinity, the word acquired its current meaning as a refuge.

An “inner sanctum”, on the other hand, refers to the innermost part of a temple into which none but initiates, priests or even the supreme priest was allowed to enter. The concept was already known to the Greeks – the “abaton” was literally a place where it was forbidden to step – and probably goes back much further; in Jerusalem the “Holy of Holies” was the inner sanctum of the temple.

So it is not at all clear what it means to call art, or this art in particular, an “inner sanctum”, but perhaps the general idea is that art is something in which we find intimate solace. On top of that, however, the exhibition is further broken down into several parts, each of which also has its own title and its typically ill-digested justification for that title, although in practice we lose sight of the categories as we go from room to room.

Despite the failure of attempts to rationalise the content or structure of the exhibition, the Adelaide event is better than the Sydney one for a couple of reasons.

First of all, it still supports contemporary art in a general sense as well as Australian art, while the Sydney event has lost sight of both in its sentimental obsession with primitivism and neurotic self-flagellation about the evils of “colonisation” – a horse that bolted a very long time ago. Secondly, the Adelaide event gives some hope that we have not entirely lost sight of the power of painting as an art that transforms the experiential world into visual meaning.

In striking contrast to Sydney, there are a number of artists here whose work engages our attention and interest. Perhaps most memorable is Jacobus Capone’s video filmed in the Arctic Circle. It is the record of a relatively simple performance in which he scratches a line into the face of the Paulabreen Glacier with a hunting knife, but the action acquires a momentous character from the grandeur of the environment and the difficulty of the circumstances.

The glacier is located at Svalbard between continental Norway and the North Pole, in the Arctic Ocean, and the work could only be filmed in the coldest part of winter, when the sea freezes, creating a solid platform in front of the icy cliff. There are two screens on opposite sides of the room, and each alternates between long shots of Capone, dwarfed by the immense mass of ice above him, drone shots and close-ups in which we watch the point of his knife merely scratching the surface of the ice cliff as he goes by. We are reminded at once of how small and vulnerable we are in the face of nature, and yet how vulnerable aspects of nature can be to vast processes that we can unwittingly set in train, such as global climate change.

Another intriguing work is by Khaled Sabsabi, which evokes aspects of the Sufi mystical tradition. All higher religions tend to develop sophisticated theological systems and to be dominated by orthodox teachers of that theology, but at the same time produce occult and mystical traditions; these are usually looked upon with suspicion, if not condemned as heretical, by the representative of orthodoxy – the word itself means “right opinion”.

The Sufi tradition, today particularly associated with Persian poets such as Rumi, is in fact a branch of Sunni Islam and predates Persia’s adoption of Shia under the Safavid dynasty. And this mystical tradition, some of whose insights coincide with those of Indian and East Asian spiritual thought, is still disapproved of by fundamentalist Muslims of all kinds.

Sabsabi’s work is a set of hangings, as though to close off a secret precinct; on the outside they are stained dark with coffee grounds, in shapes that look like the silhouettes of heads and shoulders. Inside, the hangings are covered with patterns and abstruse inscriptions of numbers and letters in Arabic script. At the far end of the space is a video which evokes the infinite space of the heavens.

Painting is represented by several artists, which as already observed is a hopeful sign, although none of them has yet fully embraced the potential of the medium. The entrance foyer downstairs is full of black and white and muted colour works by Clara Adolphs, based on found photographs of families on holiday, in the country, and so on. The idea of the found photos is interesting, but blocking them out one after the other in a minimal palette, presumably with the aid of a projector, falls far short of real painting. And while individually some of the resulting images are quite evocative, the collective effect becomes tedious since all are repetitions of a single idea.

Vivienne Shark Lewitt has a series of pictures with a fey poetic charm, but again this is timid compared to the power of real painting – engaging with the world of perception and using a full range of solid colours. Seth Birchall seems to have embraced the adventure of plein-air painting, but could approach the work with greater conviction as well as greater technical expertise.

Heather B. Swann’s works are emblematic images executed in two and three dimensional form, rather than paintings, but they are nonetheless some of the more memorable things in the exhibition, with a touching evocation of sadness and solitude.

In other media, Lillian O’Neil’s collages are effective in evoking the dislocation of a new mother and her sense of a world that is dramatically narrowed in some respects even as it is opened in others. She also uses found imagery, but the cutting and assemblage of collage allows for countless new permutations.

James Barth, an artist concerned with self-representation at the boundaries of male and female, has produced a video work with a digitally animated avatar self-image as a female dancer, programmed to mimic the performer’s own movements.

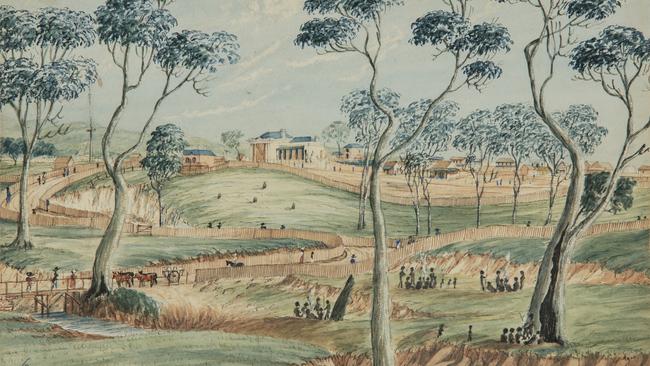

The exhibition also includes some older works from the collection, including a small watercolour by Robert Davenport, a view of Adelaide around 1843-49, when the city was still very young, for the first settlers had only arrived in 1836, and the elegant and classical urban plan was laid out by Colonel William Light in 1837.

This history was lost on a taxi driver I talked to on this visit to Adelaide, who spoke of “the olden days, when the city was built hundreds of years ago”. If you are accustomed to a very precise sense of historical time, it comes as a shock to realise that for many people, even the dates of the two World Wars are uncertain and anything earlier falls into a shapeless void where Queen Victoria, Newton and Shakespeare all seem to be roughly contemporaries.

Davenport’s picture is included because it is apparently one of the rare early images of Adelaide to include Aboriginal figures. Here little groups are gathered around fires in the foreground, while new settlers travel up and down a road fenced on either side up to the site of the city, whose most prominent building at this stage is clearly the new Government House, its present East Wing only completed in 1840. Sydney’s original Government House, modest as it was, also dominated the city, in the early days when Bridge St was its main artery.

Next to this watercolour are three monoprints by Hans Heysen, which appear to be based on photographs taken by the artist. He has executed them in brown ink, notably making good use of scratching back into dark areas, the negative technique most radically adopted by Degas, to produce tone and texture in his tree trunks, bodies of water, and so on.

Speaking of older artists, the Art Gallery of South Australia has several new acquisitions, including a fine head of a boy by Mary Beale (c. 1660s; acquired 2020) and a little Virgin and Child by Barbara Longhi, from Ravenna (after 1570, acquired 2022).

The Gallery also recently purchased (2022) a fine Jeffrey Smart, The Argument Prenestina (1982) in honour of the late James Ramsay, a great benefactor, on the occasion of the 20th anniversary of his death. This tall and narrow picture is from one of Smart’s best periods, and includes a spectacular overpass as well as the large trucks that are so often motifs in his works, whose quarrelling drivers epitomise his understated and never explicit vision of humanity in servitude to the machines and systems of the modern city.

Another new work, currently on loan, has a remarkable story. It is a Venetian Baroque painting of Narcissus catching sight of his own reflection in the pool, by Petro Negri (1628-79), and was in the collection of a Jewish couple, Benno and Ilka Korner, in Ostrava in Czechoslovakia until 1939, when it was stolen by the Nazis after their occupation of the country in 1938-39.

The family escaped, although some 8000 Jews in the city were murdered in the Holocaust. After the war, the couple fought for many years to regain possession of their collection; over 80 years later, this picture was finally returned and has since been on loan to AGSA, complementing its fine collection of 17th century painting.

Adelaide Biennial - Inner Sanctum

Art Gallery of South Australia to June 2

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout