Sidney Nolan, portraits of the Holocaust

Sidney Nolan worked on a series of portraits of war criminal Adolf Eichmann and victims of the Holocaust, in images that are being shown for the first time.

A few weeks ago, on Tuesday August 16, Mahmoud Abbas, President of the Palestinian Authority, was in Berlin seeking help and support from the German government. The cause of the Palestinian people has of course been rather beleaguered since other Arabs finally realised that they had a lot more to gain from positive engagement with Israel. Even Turkey, which has stood up for the Palestinians in the past, has just restored full diplomatic relations with Israel.

Abbas’s visit came at a sensitive time, however, approaching the 50th anniversary of the Munich massacre of September 5 and 6, 1972. Terrorists from the Palestinian Black September gang, with the help of German neo-Nazis, attacked Israeli athletes at the Munich Summer Olympics, murdering six Israeli coaches and five athletes. The crime was all the more shocking because ever since antiquity, athletes have enjoyed special immunity and have been free to travel unhindered to international competitions.

Abbas should have realised that the anniversary would be raised. At a joint press conference with German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, a reporter asked him whether he would apologise – both to Israel and to Germany – for the Munich massacre, giving him an excellent opportunity to be diplomatic, conciliatory, perhaps to reassert the justice of his cause, and yet acknowledge that times had changed and affirm his commitment to peaceful solutions. Instead, he turned an opportunity into a catastrophic diplomatic failure. He started to rant about Israeli massacres, and concluded by claiming that the Palestinians had suffered “50 Holocausts”. Of course, these remarks were denounced by the German government and opposition parties, as well as by the Israeli government. Abbas will continue to be haunted by them, for as the Latin proverb says, words spoken cannot be recalled.

Words must be used with care, particularly when they refer to grave and terrible things. The Holocaust was a unique historical event, and genocide – of which it is the most appalling example – has a very specific meaning which must not be cheapened by hyperbolic abuse. Deaths in military confrontation are not genocide; massacres and military reprisals are not genocide; ethnic cleansing and deportation are not genocide.

These are all horrible, inhumane events, in many cases wicked and criminal. But genocide is something different and far less common: it is when a systematic attempt is made, as a matter of government policy, to exterminate a particular ethnic group. The hallmark of genocide is not anger and savagery, not impulsive violence, but dispassionate and organised planning and execution.

This is what has always been most horrible and almost inexplicable about the Holocaust. One of the episodes I most vividly recall from the documentary Shoah (1985) was an interview with a woman whose job was to book rail transport to the death camps. She felt at the time that she was doing a good job because she made group bookings at a discount and negotiated a further discount for one-way tickets. Her ability to narrow her moral field of vision to the point where she excluded the appalling reality of what she was really doing was alarming, but also a reminder that we can all at times be guilty of ignoring the full consequences of our actions and behaviour.

The most emblematic case of such moral disconnection was Adolf Eichmann, who was kidnapped by Mossad agents in Argentina in 1960, tried in Jerusalem and hanged. The trial was covered by Hannah Arendt whose book Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963) was memorably subtitled A Report on the Banality of Evil. Eichmann, a complex character who had earlier proposed relocating the Jews to Madagascar – ironically a plan frustrated by the German failure to invade Britain or overcome British naval superiority – eventually defended his organisation of the Holocaust on the grounds that he was just following orders.

It is appropriately with the figure of Eichmann that Sidney Nolan began his reflection on this terrible episode in history, in a body of work long unknown and now shown for the first time in Australia at the Jewish Museum in Sydney. It is a small but powerful and moving exhibition that sets Nolan’s three series of work on this theme on three walls of the room, with photographs of Auschwitz and displays of costumes, barbed wire and other artefacts on the fourth wall.

Nolan had been interested in the treatment of the Jews in Germany for almost two decades. The exhibition opens with a kind of prelude from as early as 1939, when the artist cut out and overpainted a photograph of the Buchenwald concentration camp which had been published in The Age. In this first piece, he dramatises the horror of the concentration camp by merging it paradoxically with St Kilda Beach; in a second overpainted newspaper article he associates the prison camp with Milton’s Hell in Paradise Lost.

A 1944 painting, inspired by the liberation of Lublin, whose Jewish population had been almost entirely wiped out, shows heads trapped inside rows of windows; a later drawing from 1947 shows a body in a gas oven; an article from The Times in 1955 reveals the terrible story of collaboration by a Hungarian Zionist leader, while a couple of paintings from 1957 show Nolan thinking of treating the subject of the camps on the scale of the cave paintings of Lascaux.

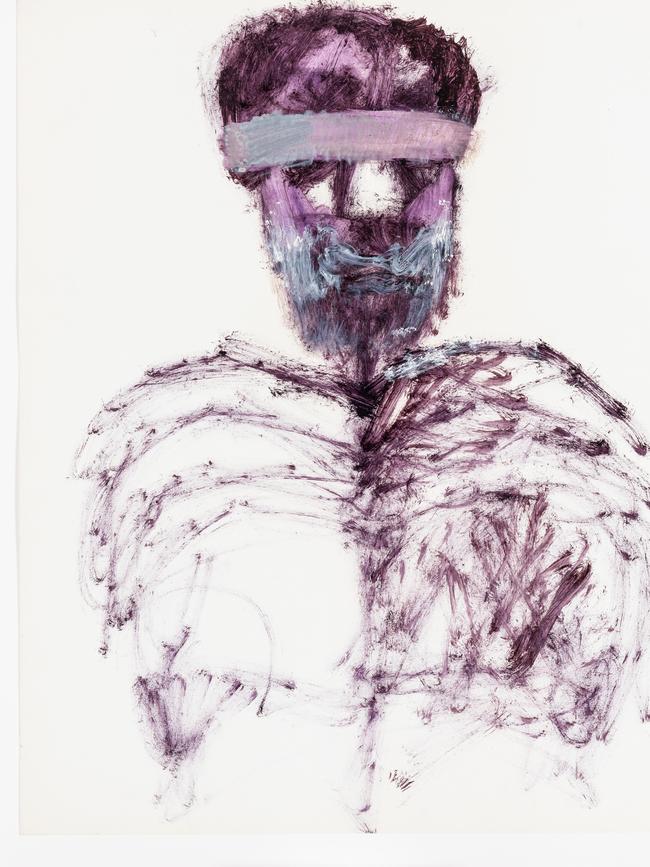

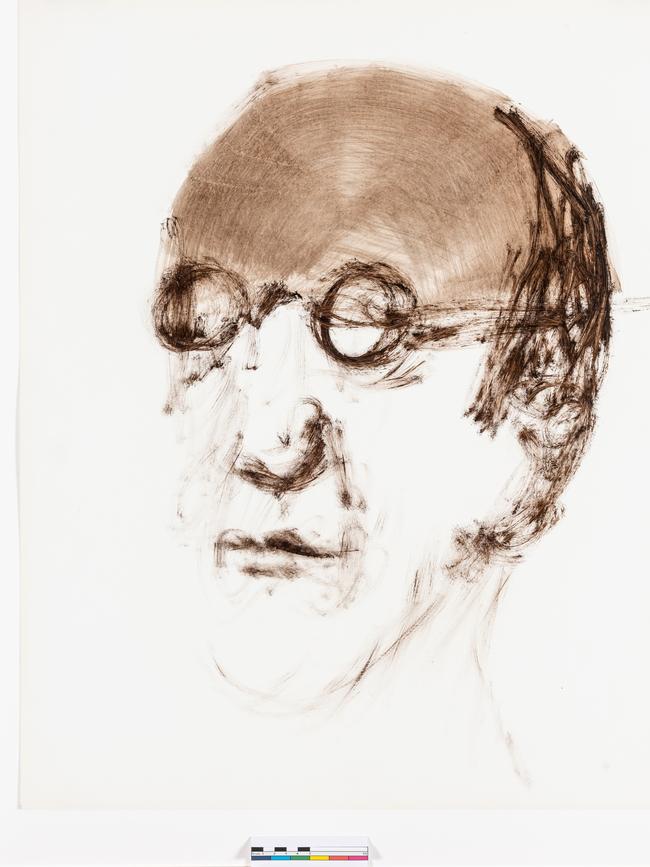

Towards the end of the Eichmann trial – shortly before his visit to Auschwitz with his Jewish friend Al Alvarez, a contributor and poetry editor at The Observer – Nolan began to paint a series of heads of Eichmann, based on newspaper photographs (November 27-December 10, 1961). Interestingly, this series of heads was made just a few years before the young Brett Whiteley became obsessed with the murderer John Christie as a symbol of evil. Presumably he was unaware of Nolan’s heads of Eichmann, since these were never exhibited. But, in any case, Nolan’s Eichmann is essentially impassible, almost inscrutable. His features appear slightly differently in each work, but the most striking difference is in the patches of light and shade that play across the defendant’s face, as though registering successive attempts to penetrate a terrible mystery.

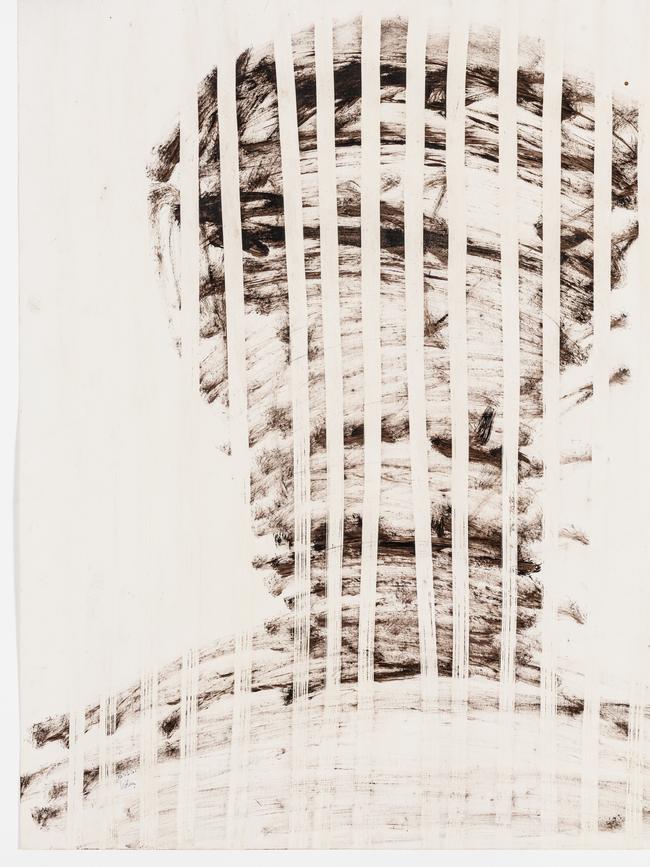

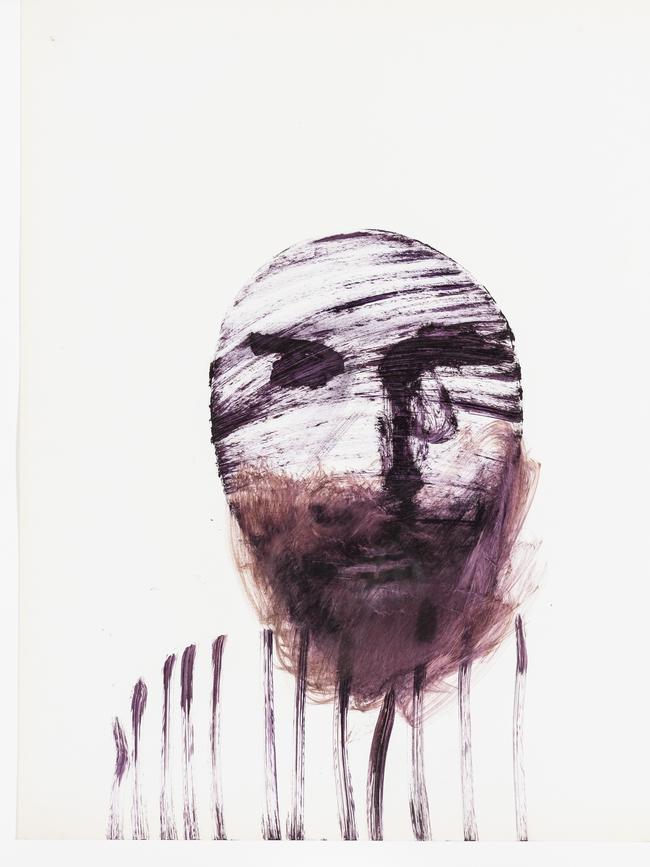

The second series of work that Nolan made in the second half of December 1961, still while contemplating a visit to Auschwitz, was a set of heads, imaginary portraits of death camp inmates. Like all the works in each of the three main series, they are monochrome, executed in brown paint on paper. Some appear relatively naturalistic, others are overtly expressionist in form: thus the first in the series looks like the portrait of a well-to-do and elegant middle-aged gentleman who might have owned a small business or a successful shop; precisely because this head is not in any way overtly emotional, it conveys the pathos of the brutal interruption of normal civilised life.

This face is disturbing, on closer inspection, in having only one eye. It sits above the summary suggestion of a torso clad in the camp uniform, whose vertical stripes, in the artist’s imagination, can also turn into the bars of a prison. At the opposite extreme are figures screaming in anguish, much less naturalistic, with vestigial features in which all is stripped away but for the experience of pain, while the torso is reduced to the schematic outline of a spine and rib cage – in which, by another imaginative merging of motifs, the ribs themselves seem to be made of barbed wire.

Nolan’s brushwork is expressive, not only in its gestural energy and urgency, but perhaps less obviously in his use of a half-dry brush, so that the marks are seldom fluent and easy, and more often harsh, scratchy and desiccated. In many of Nolan’s other series, like the Leda cycle that I wrote about recently at TarraWarra, he revels in the liquid fluidity of his media, evoking the dreamlike uncertainty of the subject. Here, on the contrary, he instinctively responds to the difficulty of articulating anything clearly or lucidly about a reality so profoundly irrational.

In this whole series, there is one image that stands out not only for its intensity, but especially because it looks almost like a self-portrait, whether consciously or unconsciously. The shape of the head and the features are like Nolan’s; the figure again lacks its right eye, but stares fixedly with the left, as though somehow a metaphor for the penetration of the artist’s imaginative vision, and the impossibility of literally seeing the faces of people now all dead.

The final series, painted just a few days after the second, on January 6 and 7, introduces an unexpected theme: the Cross and the Crucifixion. Here the victims of Auschwitz are imagined as hanging from crosses that sometimes also turn into the smoking chimneys of gas chambers; at other times the bodies are carried in carts, or piled up in carts with a cross, in one case including the hammer with which the nails were driven in and the pincers with which they were extracted – part of what are called in traditional Christian iconography the Instruments of the Passion.

These are sensitive images from a Jewish point of view, for although Christ was himself a Jew who was executed by crucifixion, his followers who believed he was the promised Messiah held their fellow-Jews responsible for their leader’s death. This was also a charge that Christians in subsequent centuries made against the Jews, long before the rise of modern racism in the later 19th century, inconceivable before the new sciences of evolution and genetics.

Nolan, of course, is in no sense reproaching the Jews, but rather taking the Cross as representing the highest degree of tragic suffering; the murder of the Jews thus becomes a re-enactment of the Passion itself. The artist simply follows his artistic instinct and his imagination as these ideas suggest themselves to him, not some line of philosophical reasoning. But perhaps he had an intuition that, like the death of Christ, the martyrdom of Auschwitz would inaugurate a new age of moral awareness.

The fascinating thing is that all of these images were made before the visit to Auschwitz at the end of January 1962. The exhibition includes several photographs Nolan took on that visit, including of the interior of cells, the outside of a gas chamber, and even what looks, perhaps fortuitously, like a cross in the snow. But he made no further pictures of the subject, nor did he exhibit those he had made before the visit. He made several attempts to imagine the subject in advance, but imagination was ultimately defeated by a reality not only too horrible or brutal, but too radically alienated from humanity to be humanly expressible.

Shaken to his Core: The Untold Story of Nolan’s Auschwitz, Sydney Jewish Museum, until October 23

Shaken to his Core: The Untold Story of Nolan’s Auschwitz

Sydney Jewish Museum, until October 23

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout