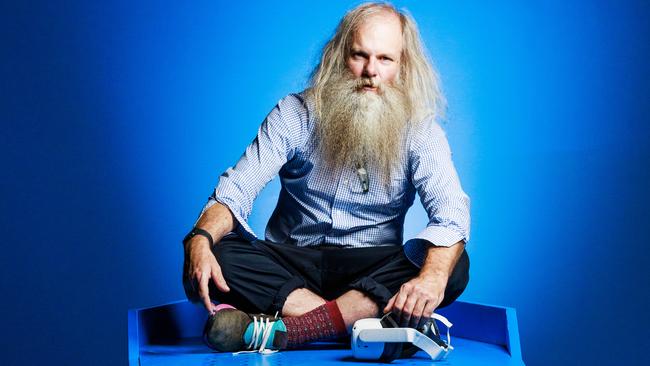

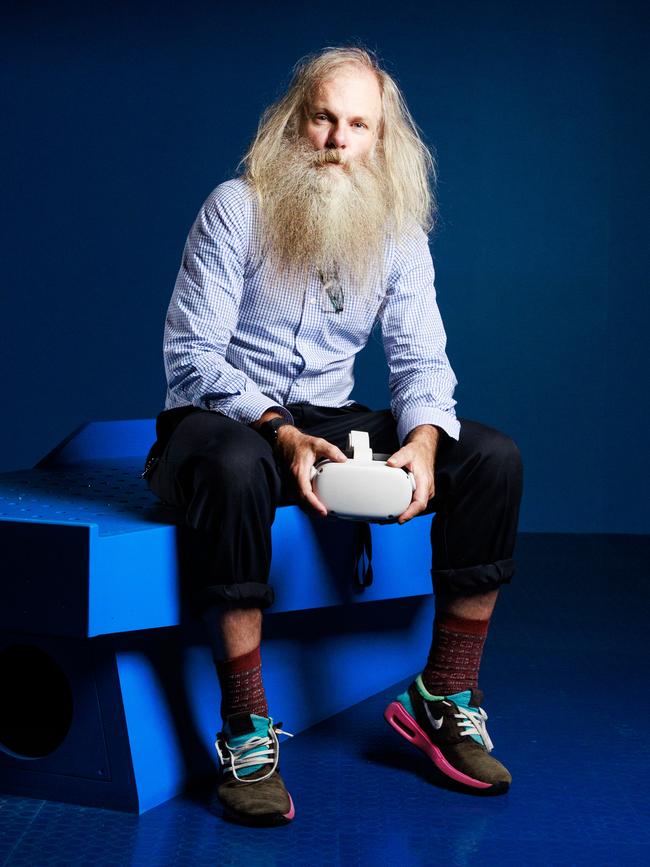

Shaun Gladwell uses virtual reality to simulate death in new National Gallery of Victoria exhibition Passing Electrical Storms

Using cutting-edge extended reality (XR) technology, Shaun Gladwell simulates the de-escalation of life from cardiac arrest to brain death in a new Melbourne exhibition.

Shaun Gladwell is terrified of storms, so it is something of an anomaly that he has spent his entire artistic career chasing them. Indeed, a brewing tempest is at the centre of the video artwork, Storm Sequence, which brought him to prominence in 2000. And the meteorological phenomenon has continued to fascinate the artist since.

Speaking down the phone from inside the National Gallery of Victoria, Gladwell, 50, has stolen a moment of solitude away from the rush of installing a new exhibition. As though time is a peripheral concern for him, he habitually muses on theories of hyperreality and aesthetic philosophy in an attempt to rationalise the artistic intent behind the work that took him from little-known artist to the attention of major galleries around the country. The work shows Gladwell skateboarding on a concrete platform as a storm closes in over a Sydney beach, its waters turgid and menacing.

“There’s this concept of the sublime in relation to the storm where it’s so beautiful from a distance,” he explains, “but when you’re in the middle of it, that’s a really powerful experience.”

The philosophy is not too dissimilar from that which is behind Gladwell’s latest body of work, Passing Electrical Storms. Using cutting-edge extended reality (XR) technology, Gladwell simulates the de-escalation of life from cardiac arrest to brain death. It will be one of the highlights of the NGV’s Melbourne Now exhibition, which opens this weekend.

From afar, his immersive installation is a masterclass in the ethereal beauty that can be produced by modern software. Yet, in the days counting down to Melbourne Now, Gladwell jokes about the things of nightmares: his sleep deprivation from virtual reality (VR) software crashing. He’s been at the eye of a storm that will pass when the installation invites its first guests to encounter a glimpse of death in the aftermath of a heart attack.

Once the VR headset is on and their pulse begins to flatline, participants experience the out-of-body feeling that Gladwell describes as “moving away from yourself and then floating off into the giant universe”.

“By simulating death as an experience in its last few minutes, it’s a meditation on the ephemerality of individual life. For me, it’s not all gloomy but a spectrum of colours and moods.”

The NGV’s Ian Potter Centre will host Gladwell and some of the most sought-after local contemporary practitioners for the free exhibition, opening again on the 10th anniversary since its first showing. This iteration will celebrate the art, architecture, and design shaping Melbourne’s culture today, according to the gallery.

Passing Electrical Storms sees a tonal shift in Gladwell’s artmaking. In his earlier bodies of work, there’s been a dichotomy between what we see – think slow-motion cinematography capturing his subjects casually at play – and the rigorous academic study he undertakes to grapple with the human body’s physical limits.

Gladwell has so seamlessly displayed the grace, and stamina, required to balance on a motorbike (Approach to Mundi Mundi, 2007), breakdance through graffitied tunnels (Broken Dance (Beatboxed), 2012), or skateboard in step with Bondi Beach’s crashing waves (Storm Riders, 2018).

“It’s very easy to get excited about the phenomena that happens within urban culture,” he says. “When the city empties out after a working week, teenagers take it over as a kind of creative playground.”

It’s a deceptive game Gladwell has played, lulling viewers into a false sense of his works’ simplicity when his interest in art theory meticulously underpins his practice. As he describes the mechanics of extending reality to evoke a dream-like state, there’s an ease with which he lists off the catalogue of philosophers – Jean Baudrillard, Michel Foucault, David Chalmers – who have influenced his latest work. And yet, his art remains accessible; after all, what’s cooler than travelling at light speed toward the edge of the universe; towards the end of being?

It has surely parachuted him to being considered the coolest dad by son, Zeno, 11, whom he shares with wife Tania Doropoulos. She, an art curator and most recently director of the Anna Schwartz Gallery, is an active sounding board in his life. And it means their son always has his eyes on the creative work they’re doing. “He’s at the perfect age to be interested in gaming and VR. We share a lot in common but there’s no pressure for him to get into art.

“My work has shifted seismically because of him. I think about death in a different sense, it’s personal now because I see life as being so dear.”

At an age similar to his son, Gladwell encountered the short documentary Powers of Ten, written and directed by American designers Charles and Ray Eames in 1977, in high school science class. The film, which Gladwell pays homage to in the second half of his installation, focuses on the relative size of humanity when compared with the size of the universe.

He remarks coyly that it was his first high-school girlfriend who drove him to focus in class because she was “super academic” and the library was the only place he could spend time with her.

–

‘Art is exhausting. I love the idea that people can take it or leave it. Or maybe they come back to find meaning in it a year later.’

–

He recalls, “I remember being blown away [by the film] because it starts with a zoom on two ordinary people having a picnic in Chicago. And then you fly from the surface of the Earth right out to what was the observable edge of the universe.

“I always thought, when I die, the most beautiful thing I can see will be how big the universe is.”

The world as Gladwell’s explorable muse shrunk considerably with the beginnings of the pandemic. For an artist predominantly working in visual performance, with a casual hobby in marathon running, his life in constant motion was brought to a standstill by the incessant Victorian lockdowns.

Taking creative liberties to interpret the state government’s eased lockdown restrictions, Gladwell invited two friends – a cinematographer and a grip – to live with him at his North Melbourne home. Homo Suburbiensis, which mixed media of painting and video together, was born out of Gladwell’s desire to test the limits of creative possibility.

Inner-city streets were substituted for a BMX bike on the kitchen bench and brillo boxes became yoga platforms to remind audiences his fascination with fringe culture remained. He’s grateful, however, to be back in the office – or in this instance, gallery.

“Going from lockdowns to this joyous process of making work in a community of people [within art institutions] is an absolute privilege,” he says.

His return to the NGV is a welcome addition to the string of shows he’s previously headed up at Melbourne’s Anna Schwartz Gallery, which he is represented by, and Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art.

Having studied at the University of Sydney, University of NSW, and later Goldsmiths at the University of London, Gladwell is one of the country’s most collectable and well known contemporary artists, with works held by the National Gallery of Australia, Sydney’s Museum of Contemporary Art, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art. Even Elton John sits among a number of high-profile collectors.

“I’m one of many. He’s got a very big personal collection. So I don’t want to feel too special,” Gladwell says with typical humility.

His relationship with critics in this country hasn’t always been as smooth. He’s aware digital art can be a tough sell for some. For others, he questions whether they choose not to venture further than the entry point of his work.

Does it concern him?

“Art is exhausting,” he says, “I love the idea that people can take it or leave it. Or maybe they come back to find meaning in it a year later.”

But when asked if he cares about having his work misrepresented, he quips: “I really do like the idea of art critics being obsolete.”

He says he is more worried about what those closest to him have to say.

Even now, there’s uncertainty in his voice when he mentions a photograph of his, recently hung in Parliament House as part of its permanent collection. He’s not sure how it’ll be received by the more radical of his peers. It’s a striking visual of desert dust against a post-apocalyptic landscape from his 2009 MADDESTMAXIMVS series, which pays homage to the dystopian Mad Max films. It was once part of his submission to the Venice Biennale, but he worries its meaning has been neutralised.

“It’s super exciting, but in a political context it could be seen as the worst work I’ve made now. I wouldn’t expect my friends and colleagues to even go there to see it.”

When probed on how this discomfort with being inserted into Australia’s political landscape translates from his time in Afghanistan as an official war artist in 2009, he is philosophical. “I’ve had a moral hangover since.”

Growing up in a military family, Gladwell’s grandfather served in World War II and his father fought in Vietnam. He admits there was pressure from his parents to serve in the defence force after high school, but the most stress was that which he placed on himself. Perhaps out of frustration, or adolescent confusion, he went in the complete opposite direction. The path he’s taken hasn’t always been conventional but he’s carved a niche for himself at the forefront of digital art.

Reluctant to take position as one of the trailblazers leading the foray into XR on the Australian art scene, Gladwell is adamant his success has been built from collaborating with the teams behind the technology. Supported by a research partnership with Deakin University’s Motion Lab, Gladwell credits Leo Faber, executive producer of Factual and Culture at the ABC, as “the single individual who convinced me that the technology was at a point where it was practical to start working in the realm of VR”.

But the software powering his installation is only the starting point of what NGV senior curator Ewan McEoin has called a “deeply affecting experience”.

“We still think of VR as a game. But Shaun hasn’t designed a game. Critics may mistakenly think his art is about the technology. It’s not, it’s a vehicle for creating, what I suspect will be, an extremely poignant moment for people.”

Shaun Gladwell’s Passing Electrical Storms is part of the NGV’s survey exhibition Melbourne Now, held March 24 – August 20

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout