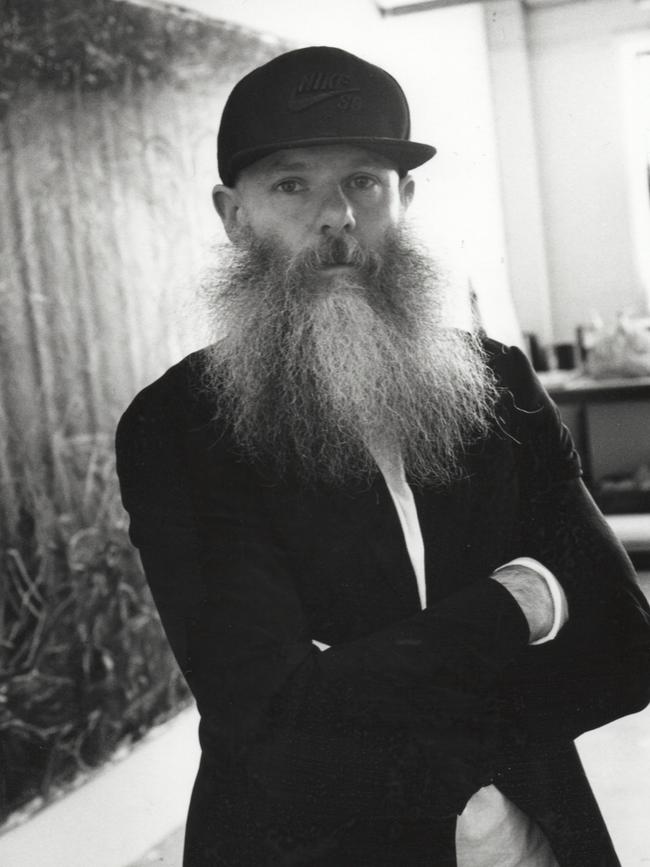

Where soul meets body in Shaun Gladwell’s art

Exploring the limits of the flesh and perception has been the hallmark of much of Shaun Gladwell’s video work.

Life motivates art. The great Dutch painter Piet Mondrian, for instance, was a lover of boogie-woogie. His black-painted grids with their blocks of colour can be understood in relationship to the rhythm and duration of a jazz composition.

Similarly, Australian painter Robert Hunter was a seasoned pool player, and the six pockets and grid of the billiard table influenced the crisscross composition of his paintings.

In the same way, artist Shaun Gladwell is engaged with skateboarding, surfing and other types of urban sports and practices. These activities are the inspiration for his art.

“When I saw director Stacy Peralta’s seminal skateboarding video Future Primitive (1985) at the age of 13,” he says, “particularly Rodney Mullen’s virtuosic part, my life as a skateboarder, and later an artist, was changed forever.”

Future Primitive, with its up-to-the-minute soundtrack and fast on the ground moves, profiled a new generation of skateboarders, many of whom are now household names in the skating world.

Flying across the surface of the ocean on a surfboard shares the same emotional resonance and anarchic spirit as skateboarding. These are activities that transport you, that have you test and negotiate your physical limits and your perception.

Reading and catching a wave offer a type of freedom, a pursuit beyond the strictures and regimen of everyday life. When Gladwell surfs or when he performs a kickflip on his skateboard, he is searching and reaching out to fathom something that is both within and beyond himself.

The action itself is the quest for meaning and resolution. With clear single-mindedness, Gladwell channels his mental passion and physicality, harnessing existential pursuits to gather insights that lie at the limits of his body and perception, and he magically, imaginatively, filters these inspirations into art.

He also seeks others who work at the edges of physical risk and fear who, like him, wish to explore the limits of their bodies and minds.

Time and motion

Gladwell’s videos often present a single body in a chosen location performing different actions.

Storm Sequence (2000) shows a figure freestyle skateboarding on a ledge above the sea during an impending storm; Pacific Undertow Sequence (Bondi) (2010) portrays a surfer sitting upside down on a board in the ocean; Approach to Mundi Mundi (2007) shows a helmeted, leather-clad man riding a motorbike into a barren landscape with his arms outstretched; and Tangara (2003) presents a man hanging upside down from the hand rails in a moving train.

These four key works demonstrate how Gladwell’s videos are not straightforward depictions. They are highly considered and non-conformist, their mise en scene planned, and they demonstrate how bodies relate to, and can inscribe, their environments.

These works stress the flow, energy and propulsion of bodies in motion.

Physical intensities in the videos include the gathering storm clouds and rain that background and impact on the skateboarder in Storm Sequence; the intervallic waves pushing the upturned body under the water in Pacific Undertow Sequence (Bondi); the rider gracefully balancing his body and opening his arms in parallel to the vast horizon line of the Mundi Mundi plains; and the gathering of blood in the head and the tension in the arms of a man boldly suspended wrong way up inside a moving night train in Tangara.

The prowess and athleticism of the body is the epicentre of Gladwell’s work. The body is the anchor point of his earliest figurative paintings, and his videos, parkour photographs and more recent experiments in virtual reality. These are bodies centred in the frame, presented in slow motion and often feeling the impact of gravity in the air, in the water or on land. They are bodies under duress or exertion.

The slow-moving pace of the videos is his signature. In Storm Sequence, the artist’s languid motion on the skateboard, the storm and the location combine to mesmerising effect. While the aesthetics of slow motion is important because it draws attention to the details and the emotions of the moment, time is articulated in different ways across Gladwell’s work. In Approach to Mundi Mundi, for example, he outlines further the importance of time, and how with that work he wanted to record a place over time.

Approach to Mundi Mundi refers to the antihero in George Miller’s Mad Max trilogy of dystopian films. More obliquely, it gestures towards Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, a perfectly proportioned “universal” man drawn with outstretched arms touching the edges of a circle.

Aesthetic dynamic

Beyond these sources of inspiration, Approach to Mundi Mundi is a work of psychic intensity in which the landscape opens up before your eyes in the same way the rider embraces its vastness with open arms. The idea of capturing the plains at dawn and in full sunlight, of experiencing the changing conditions of the landscape across time, is something we encounter in several of Gladwell’s works. He searches for that spark of the transcendent. With influences running in many directions, he is deeply committed to the study of art, artists and philosophy.

For Gladwell, his work has always conjoined the past and the present, creating a temporal arc between the stillness of the body in paint and forms of bodily expression in video. Indeed, it could be said that in this way his work is a 21st-century transformation — an innovation — of time-honoured traditions in art.

Painting represents the starting point of his art-making. Painting provides the tools and the means, and it is the bedrock of his thinking, whether his work is in the museum or on the streets. Much has been written about the relationship between the aesthetic dynamics presented in Storm Sequence, for example, and those of the turbulent, romantic landscape paintings by British artist JMW Turner, and in particular German painter Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (c.1818).

Rooted in art history

Gladwell recalls when he was six years old visiting the Art Gallery of NSW and being stunned by Frederick McCubbin’s On the Wallaby Track (1896).

He also writes of closely studying Helen Gardner’s Art Through the Ages (1926) when he was in high school, particularly taken by a reproduction of Hans Holbein the Younger’s The Ambassadors (1533) and its famous anamorphic skull.

These are important influences that have recurred again and again in Gladwell’s work during the past 30 years. The Australian landscape depicted in McCubbin’s painting looms large in Gladwell’s imagination.

Skulls, bald and uncovered or shown inside bike helmets, continue to appear in his work, particularly in the drawings and prints, as a metaphysical symbol of mortality and fragility. In Holbein’s painting, the skull describes the limits of perception; it is a puzzle, a sharp anamorphic perspective that correlates to the dizzying blind spot that Gladwell strives to illuminate in his art.

VR has enabled Gladwell to reimagine the anamorphic skull of his youth and see it from all sides. Orbital Vanitas (2017) is a 360-degree video that references Holbein’s skull but in an enormous three-dimensional form that the viewer can float through.

Exploring the limits of his body and his perception has been the hallmark of much of Gladwell’s video work, and this is now translatable into a fully immersive encounter for the viewer.

Orbital Vanitas traverses time and space — you glide inside a skull to see a representation of the world from the inside out. It is similar to the described sensation of riding a tube wave but without the water; you are standing on top of the world, you are that dizzying blind spot.

In many ways the painting Cosmology (Air Antwerpen) (2011) encapsulates these feelings and ideas. The work shows sprays of silver that resemble starbursts in the night sky, painted across the surface of boards.

This is the culmination of many influences — from graffiti to the profundity of the night skies and the evolution of our cosmos, as alluded to in the title.

Quest for meaning

While there is no actual performing body in this work and no central horizon line, this painting references something more. This is an artist whose work reflects on the relationship between the past and the present, between our bodies and the spaces we inhabit, from the enormous scale of the universe to the specifics of the street, to the perceptual and physical limits of the body and the mind: the ultimate quest for meaning.

In the end nothing is part of everything. It’s a dizzying blind spot. It’s a philosophical conundrum, in the same way that riding a wave is an endless chase, where, as American writer and psychologist Timothy Leary described it, “your future is right ahead of you, the past is exploding behind you, your wake is disappearing, your footprints are washed from the sand”.

Natasha Bullock, assistant director of curatorial and programs at the National Gallery of Australia, is the co-curator of Shaun Gladwell: Pacific Undertow, showing at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney from July 19. This is an edited extract from her catalogue essay for the show.