How ‘Insta-poet’ Rupi Kaur turned the literary world on its head

Rupi Kaur has reimagined an art form for an entire generation who may never have otherwise laid an eye on a poem.

Poet Rupi Kaur connected with thousands of readers before her work was ever printed on a page.

The 30-year-old Canadian is credited for founding a new medium of social media-centred art: Insta-poetry. Indeed, with her 2014 debut collection Milk and Honey having sold more than 3 million copies and having been translated into 25 languages, she has made the art form her own.

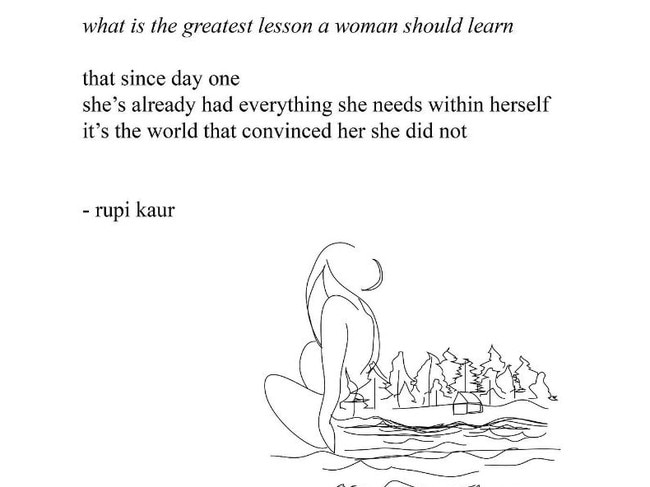

Insta-poetry’s structure consists of an unpunctuated stanza, written in lower case and presented with delicate illustrations of people entwined with nature in the corner of a single Instagram tile. Those tiles are then spread across social platforms, and reshared on Twitter, Tumblr and Facebook.

Often centred on the themes of love, abuse, colonisation, genocide and empowerment, Kaur’s works speak to an entire generation of mostly young women who may never have otherwise laid an eye on a poem.

In changing the medium, and growing its online audiences, she has become a pseudo-spiritual guide of mass celebrity – although she is hesitant to admit it.

“I don’t see myself as a celebrity,” she says with a laugh. “My team and people will use that word and I’m like, that’s so weird. I guess it’s just not a part of my identity.”

Kaur is speaking to Review over Zoom ahead of the Australian leg of her world tour, wherein she will take to the stage for spoken-word performances, including readings from her various works.

The poet, who boasts a staggering four million Instagram followers and is a New York Times bestselling author, was writing verse before she even knew what it was. Born in the Indian state of Punjab, she emigrated to Canada with her parents when she was four.

“It’s hard for me to pinpoint the first time I was writing poetry,” she says. “I was also writing for friends on their birthdays, or writing about my crushes.

“I was looking back at my sketchbooks from art class a couple of months ago while I was visiting my parents. I was flipping through them, and I was speechless because they were full of drawings with words written in the top left corner. I was doing this before I even knew that I was doing it.”

Kaur recalls that her parents were always very serious while she was growing up. They encouraged her to learn Sikh arts, and the Punjabi language, while immersing herself in the culture.

As she fully began to understand her heritage and the intense oppression her parents felt after escaping the 1984 Sikh genocide, her creativity found a new purpose. She says she used the art form to try to heal a deep, intergenerational trauma that had scarred her community for decades. “I’ve always been absorbed in what happened to us – not just our sorrows, but also our joy at how resilient we are,” she says. “That was a source for some of my earliest poetry performances.”

The massacre saw 2800 Sikhs killed in Delhi and 3350 nationwide, according to government data. Independent sources estimate that number to be much higher. Riots were sparked when Indira Gandhi, the-then prime minister of India, ordered an attack on the Sikh Golden Temple. Her aim was to silence growing demands for Sikh religious and political autonomy, and resulted in the deaths of 492 civilians. Gandhi was assassinated by her two Sikh bodyguards in retaliation, and violence ensued.

“My parents’ generation survived a genocide, and so there was a lot of pain there. A lot of my community, my Punjabi Sikh community, emigrated to Canada at the time,” she says.

“My parents’ generation was dealing with those scars. A lot of the men had been tortured at the hands of the Indian state and wrongfully imprisoned and they didn’t know how much it affected their mental health. Their wives or their children really suffered.”

She says the idea of survival has been a constant thread throughout her family’s life.

“We didn’t come over because we had money, we came over because we were being killed. A lot of the focus for my parents’ generation was just surviving and getting by,” she says.

Kaur’s wordscatch in her throat as she remembers when her father came on tour with her at one of her first spoken-word shows in India. It was then she realised the importance of processing her feelings.

“It was really emotional,” she says, pausing. “What it showed me is that his generation might not know how to have conversations, because they were never taught to, but I’m going to have to learn how to start those conversations so that I can build this relationship with him. Because, the truth is, we’re not here forever.”

-

‘It’s been a journey, it is messy, but I feel more confident and powerful than I’ve ever felt before.’

-

The poet has taken her heritage into her work; she deliberately omits capital letters from her poems as a way to acknowledge her Punjabi heritage, whose language uses lower case only.

“I know how to read and write Punjab and there was even a time when I tried to write poetry in Punjabi, but it was very difficult,” she says. “It’s a language that’s been disappearing and there’s been a state-sponsored effort to eliminate it since the ’70s and ’80s. So the language is really important to me, but because I couldn’t write poetry, I was like, what other elements can I use? The Gurmukhi script has no punctuation other than periods and there’s no case distinction, so I thought that was a fun little thing to play with.”

Kaur came to prominence in 2015 when an image of her menstruating while lying outstretched on a bed set social media alight. As an undergraduate student at the University of Waterloo in Ontario, she was doing a class project to demystify stigmas around periods, and testing whether Instagram would remove such a photo. It did, and Kaur took to the platform to air her disgust that Instagram’s “misogyny was showing” by censoring the image for violating community guidelines. Her stance against the platform was deemed brave in the public eye. Her popularity skyrocketed and Milk and Honey, which would eventually outsell Homer’s The Odyssey, was picked up by a prominent publisher a year after it was first self-published.

Kaur’s second poetry collection, The Sun and Her Flowers (2017), debuted in the top spot on the New York Times paperback fiction bestseller list.

And her most recent offering, Healing Through Words (2022), is a carefully curated collection of exercises encouraging the reader to write their own poems through a style Kaur has coined “free-writing”.

“Before I got published, I never experienced writer’s block. The problem then was that I couldn’t stop writing. The poetry wouldn’t stop coming to me,” she says.

“I remember in university all the girls would get together, and everybody’s doing their hair, their makeup. People are drinking, the music’s on. We’re going to party.

“But then I’m nowhere to be seen because I’m in my room, being like, ‘Guys, hold on’. Suddenly, I’m on my Google Docs editing a poem on abuse while putting on my mascara. That was a time when it just flowed, because there was no pressure.

“Unfortunately, the writer’s block hit after that, when I had an audience where I felt like people had expectations of me, and it’s a big reason that I wrote my latest book, because I want people to know that I experienced writer’s block.”

Kaur says authors should “not to focus on the result or the outcome”.

“That’s not what writing is about. It’s about the journey. Healing through words is a bunch of rough drafts,” she says. “I think free writing really just gives you permission to open up and get creative. I truly do use those writing exercises to write myself, which is why I felt very confident that my readers would really enjoy them.”

Kaur’s poems untangle complex, universal emotions with skill and precision, according to some critics. But hers has been no warm welcome to the poetry establishment. Other critics have condemned Kaur’s work as overly simplistic, while many in traditional poetry circles dislike the use of visuals in her work. Indeed, those criticisms have seen the term ‘insta-poet’ used by some as an insult.

She was accused of plagiarism in 2020 after fans spotted alleged similarities between her work and that of Tumblr poet Nayyirah Waheed, who shares her style of short, sharp sentences and minimal punctuation. Kaur denied the allegations, and as the waves of criticism receded, her popularity only continued to grow.

As she has matured, so too has her work. Kaur’s earlier works about love are messy and relatable. These days she’s a “lot more tempered”.

“The way we feel love as teenagers and in our early 20s is just so intense,” she says. “We’re still learning and growing, and our brains haven’t fully developed yet. You can see that in Milk and Honey and really feel those intensities, and that’s why so many people were drawn to that book.

“But now, I’m in my “Khalil Gibran” era. At 30, I love his poem on marriage and I’m beginning to see love as a more balanced partnership. I’m really excited about that.”

But what about loving herself? In one of her more popular poems Kaur writes: “Loneliness is a sign you are in desperate need of yourself.” It’s been a journey, she says, but she’s almost there.

“Healing is not linear,” she says. “(But) I’m in a better place, knock on wood, than I’ve been in compared to probably the last seven years. It’s been a journey, it is messy, but I feel more confident and powerful than I’ve ever felt before.

“The way I see my identity now is like, I’m an artist, I’m a poet, I’m Punjabi, I’m Sikh, I’m a woman.”

Rupi Kaur will perform at Melbourne’s Hamer Hall on Sunday, March 26; Brisbane’s QPAC Concert Hall on Wednesday, March 29; and the Sydney Opera House on Saturday, April 1

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout