Albert Tucker among Australian artists influenced by TS Eliot

Albert Tucker and John Brack are among the Australian artists influenced by this important poem, whose 100th birthday deserves more recognition from our state galleries.

Giorgio de Chirico is often associated with the surrealist movement, but his style of “metaphysical” painting was in reality a precursor to surrealism. That movement grew out of Dada after World War I, and the first Surrealist manifesto was published in 1924 – another centenary fast approaching.

Metaphysical painting, on the other hand, was one of the many competing styles that made the decade before the war the most active moment in the history of modern art. De Chirico (1888-1978), who was born in Greece to a family that had originally migrated from Rhodes to Sicily 500 years ago, after the Ottoman conquest of the island, produced his first metaphysical painting, The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon, in 1910, and exhibited in the Salon d’Automne in Paris in 1912.

This early painting was loosely based on the Piazza di Santa Croce in Florence, with the Franciscan church replaced by a rudimentary Greek temple, a headless statue, figures of a poet and a philosopher, and in the distance behind the line of rooftops, the sail of a ship. Perhaps the ship recalls another detail of the painter’s life: he was born in Volos, near the site of ancient Iolcos, from whose port Jason and the Argonauts set out on their quest for the Golden Fleece.

In the most characteristic compositions of the next few years, de Chirico continues to use the motif of the empty square, but now often accompanied by elements that allude to the ancient and recent history of Italy. Long arcades evoke antiquity in a simplified form that curiously anticipates the style of the EUR site in Rome built a couple of decades later. Industrial towers and trains refer to the modern and industrial world, while statues recall the ubiquitous celebration of even the most minor figures of the Risorgimento in post-unification Italy.

The silence and stillness of these scenes, disconcerting as they are, is a world away from the turbulence, vehemence and even hysteria of Albert Tucker’s paintings. And yet, as we learn from a small but thoughtful exhibition at Heide, there is an interesting connection. Tucker was well aware of de Chirico’s work, which appealed to him in spite of the difference of temperament, and many years later the two met in Rome, in 1954.

The meeting was arranged by Gino Nibbi (1896-1969), who had earlier encouraged Tucker’s interest in de Chirico in Melbourne. Nibbi, who had opened the Leonardo bookshop at 166 Little Collins St in 1928 – “under the auspices of the Italian Government” according to a contemporary article in The Age – to foster cultural relations with Australia, anticipated the work done in more recent times by the Italian Cultural Institute in Sydney (founded 1977). Nibbi closed the bookshop in 1947 and returned to Italy, where he opened the Galleria ai Quattro Venti.

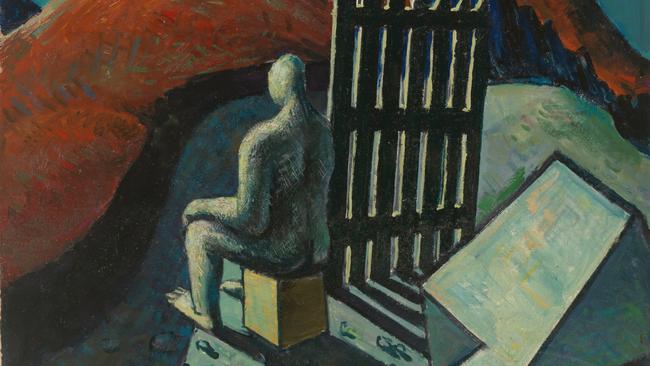

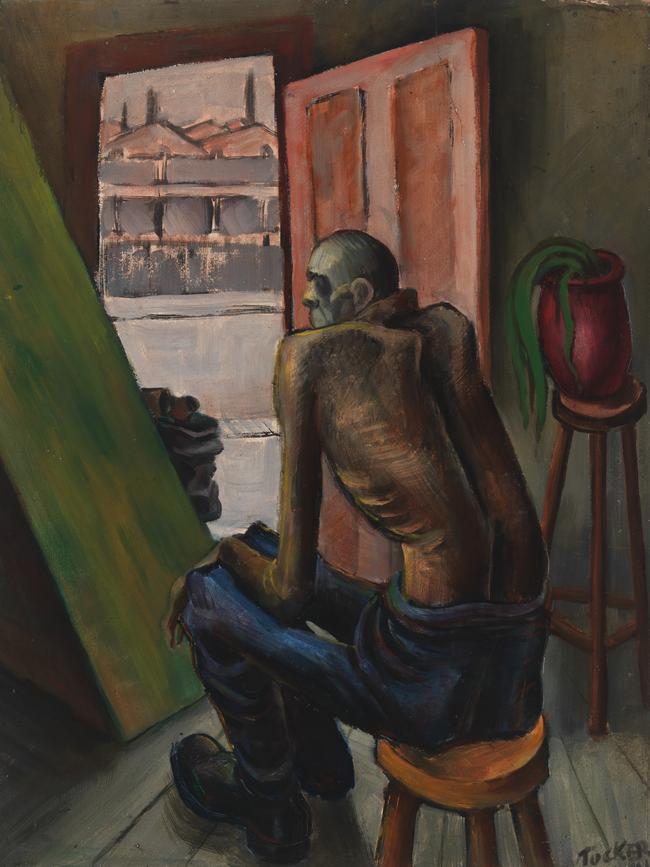

The exhibition demonstrates connections at several unexpected points, including the direct formal echo of de Chirico’s The Philosopher and the Poet (1913) in Tucker’s Spring in Fitzroy (1941), where de Chirico’s pensive figure seen from the back becomes Tucker’s hunched and desperate unemployed worker, and the blackboard in the original becomes an unexplained green wedge in the second work. Tucker’s earlier Philosopher (1939) also adapts the figure seen from behind, but in other respects is much further from his model.

De Chirico’s cityscapes also reappear in Tucker’s art, although in a very different mood and expression – often as nocturnes, typically dark and overtly threatening, and often with lurid narrative content, as in the Images of Modern Evil series painted during the years of World War II. Other themes include allusions to classical antiquity, and the replacement of human figures by dolls and mannequins.

Two of the Tucker paintings in the exhibition are of particular interest in recalling another important influence on him and other Australian artists, that is the work of TS Eliot. It is remarkable that no museum in Australia has thought of commemorating the centenary this year of Eliot’s enormously influential poem The Waste Land – possibly the single most influential poem of the 20th century.

The omission is all the more striking when we consider the lacklustre quality of exhibition programming at the most important art museums in Australia, and the dismal new shows that have recently been announced both at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne and even more depressingly at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra.

More will be said about these disappointing programs in due course, but for the moment let us consider how easy it would have been to curate a significant exhibition not only about this great poem, but more generally about Eliot’s influence on modern Australian art.

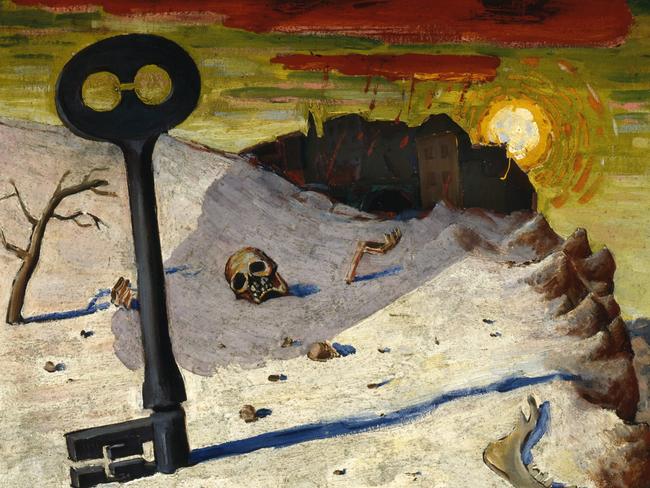

The present exhibition includes Tucker’s not very good painting that is titled The Waste Land (1941), as well as the more impressive The Futile City (1940). This second picture alludes more specifically to Eliot’s subsequent masterpiece The Hollow Men (1925); several motifs in the following lines (star, hand, jawbone, and so on) are explicitly illustrated in the painting:

This is the dead land

This is the cactus land

Here the stone images

Are raised, here they receive

The supplication of a dead man’s hand

Under the twinkle of a fading star

[…]

In this valley of dying stars

In this hollow valley

This broken jaw of our lost kingdoms.

Tucker also painted We are the Dead Men (1940), whose title is the first line of The Hollow men. And his late series of portraits, including that of Bernard Smith (1985), has the collective title Faces I Have Met, which comes from Eliot’s earlier work The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock (1915).

He is not the only painter to respond to Eliot. James Gleeson’s We Inhabit the Corrosive Littoral of Habit (1940) evokes the image of the “hollow man”, and the surrealist sculpture Madame Sosostris, which he made with Robert Klippel (1947-48), is inspired by a character in The Waste land:

Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante,

Had a bad cold, nevertheless

Is known to be the wisest woman in Europe…

Gleeson’s later painting Phlebas the Phoenician (1951) is another character from The Waste Land:

Phlebas the Phoenician, a fortnight dead,

Forgot the cry of gulls, and the deep sea swell

And the profit and loss.

Jeffrey Smart’s The Wasteland II (1945), in the Art Gallery of NSW, is another work to cite Eliot’s title explicitly. And Smart, too, had a favourite character from the poem, Mr Eugenides, the louche Smyrna merchant, who appears in a couple of paintings, with the odd addition of Eliot’s initials. TS Eugenides, Piraeus (1971) sets the ambiguous figure in his bathrobe on a rooftop, alluding to the merchant’s sexual proposition:

Mr Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant

Unshaven, with a pocket full of currants

C.i.f. London: documents at sight,

Asked me in demotic French

To luncheon at the Cannon Street Hotel

Followed by a weekend at the Metropole

He appears again, this time in a suit like some of the figures who are almost alter egos of the artist, in Mr TS Eugenides, Morning, Shaftesbury Avenue (1978), strolling past a surveillance camera mounted on a post with a strangely suggestive vertical slit. But Smart was increasingly drawn to the different vision of Eliot’s later Four Quartets, which he often quoted in conversation as well. The little-known painting To Know the Place for the First Time (1961) is titled with a line from Little Gidding (1942), the last section of Four Quartets:

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

In a much later picture, The Red Warehouse (2003), the opening lines of Burn Norton (1936), which later became the first part of Four Quartets, are inscribed on the pole in the foreground:

Time present and time past

Are both perhaps present in time future

And time future contained in time past.

If all time is eternally present

All time is unredeemable.

There are indeed many other cases of Eliot’s influence in Australian art, and although I am only citing here examples I have been familiar with for years, I discovered in the course of preparing a recent talk on this topic that David Hansen of the Australian National University has looked into the subject in greater depth. His essay This Broken Jaw: TS Eliot, Ern Malley and Australian Modern Art, can easily be found online if readers are curious to follow this theme further.

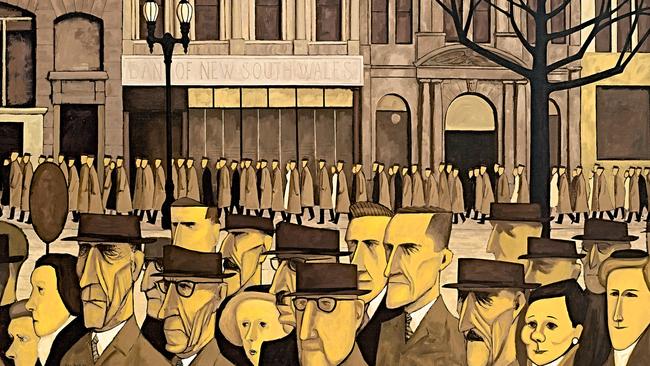

One of the most important references to The Waste Land, however, and one I have mentioned before, is John Brack’s Collins Street, 5pm (1955), a memorable painting of worn-out and gaunt city workers trooping back to their commuter trains at the end of a long day of ultimately meaningless and unrewarding drudgery in an office. The painting recalls these famous lines from The Waste Land, although Eliot is writing of the commuter crowd arriving at work in the morning, not leaving in the afternoon:

Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

But what in turn makes these lines so important is the reference to Dante which Eliot explicitly acknowledges in a footnote to the poem. Indeed, his lines are almost a direct translation of this passage from Inferno III, 55-57:

e dietro le venía sí lunga tratta

di gente, ch’io non averei creduto

che morte tanta n’avesse disfatta.

In the Inferno, these lines refer to a crowd of dead souls that, as we learn shortly afterwards, are those of people who failed to take initiative or responsibility in life; they were the people who just followed instructions, who made no commitment for either good or evil. They are too vile to be admitted either to Heaven or to Hell, and so they are condemned to blow around in a futile gale for all eternity.

It is this layering of allusions and recollections that gives Brack’s painting depth and moral seriousness, although its basic meaning is readily intelligible and even unmistakeable. The Eliot connection is doubly interesting because it refers in turn to the colossal figure of Dante, who has himself had an immense effect on modern art and literature since his rediscovery in the romantic period. Last year was the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, an occasion for great celebrations in Italy and elsewhere.

In Australia, commemorative displays were mounted at the state libraries of NSW and Victoria, and at Fisher Library at the University of Sydney. But like so much else, this important date, and this opportunity for a substantial exhibition, escaped the managements of our state and national art museums.

Albert Tucker – The Modern Metaphysical, Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, until October 23

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout