The first of these is a survey of drawings by Lloyd Rees, who was born in Brisbane in 1895 and received his original art training at the city’s Central Technical College, before moving to Sydney in 1917 to work for the advertising firm Smith and Julius.

This was no ordinary advertising agency, however, for it was owned by Sydney Ure Smith, himself a fine etcher as well as the publisher of Art in Australia (1916-42) and The Home (1920-42), the two most important journals of art and design in Australia.

Rees thus found himself at the epicentre of Australian art and in touch with most of his important contemporaries. He travelled in Europe in 1923-24 and pursued further studies at the Chelsea Polytechnic College in London before returning to Sydney, where he executed the extraordinarily fine drawings that were exhibited in the Museum of Sydney’s Lloyd Rees: painting with pencil, 1930-36 (2016).

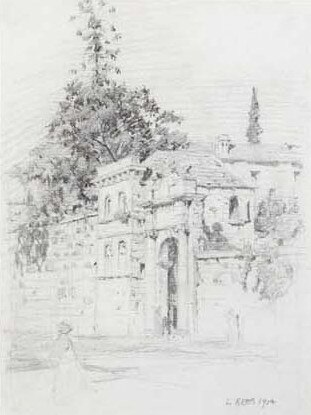

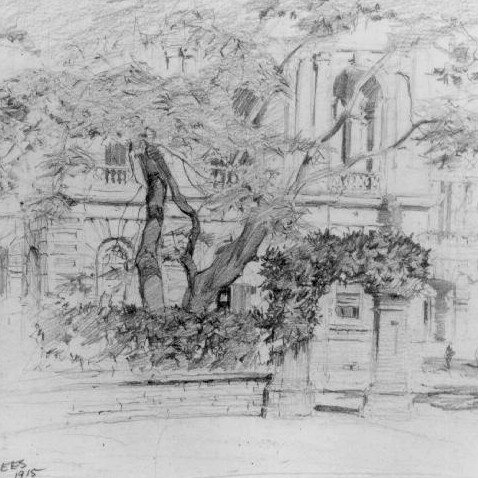

The drawings in the present display are little sketches of Brisbane, and were all made between 1912 and 1915; that is, from the age of roughly 17 to 20. They are thus in a sense juvenilia, but the juvenilia of genius. The motifs are ostensibly architectural, and the young man already draws architectural forms with astonishing confidence and subtlety of touch. He manages to convey the character of quite elaborate buildings without plodding over every outline and detail. Already, at this very early age, he has learned to suggest and to evoke.

But he has also understood that architecture is immensely enhanced by its dialogue with nature, and what really makes the charm of these drawings is that they are as much about the trees, the hedges and bushes that surround and frame the buildings as about the buildings themselves. Thus he sees one building through the silhouette of a beautiful old tree, another appearing from behind a fringe of greenery. The implicit life of the buildings is mysteriously animated by the breathing presence of the natural forms that surround them.

These drawings are also fascinating in revealing a Brisbane that was once far more aesthetically appealing — even if by all accounts stodgily conventional — than the congested urban fabric connected by expressways and overpasses that the city has largely become today.

It is almost a shock to see that it once had buildings of a scale that could enter into a meaningful dialogue with trees and other elements of a natural landscape.

Next to this display is a large gallery devoted to women artists of Brisbane of the last century. The first impression is striking, but the room is hung in a salon style better suited to works that are more or less consistent or compatible in vision; the fundamental problem with this exhibition is that the work is so radically disparate in style and quality, and this problem is aggravated by the hanging, which creates a visual and aesthetic cacophony.

‘The motifs are ostensibly architectural, and the young man already draws architectural forms with astonishing confidence and subtlety of touch’

We are also very far from the skill, refinement and subtlety of the Lloyd Rees drawings. There is perhaps only one artist here who really stands up to this comparison, and that is Gwyn Hanssen Pigott, represented by one of her exquisite groups of ceramic vessels, in a presentation that deliberately recalled the still life paintings of Morandi. Pigott’s consummate skill on the potter’s wheel allows her to produce forms that are delicately poised between the classic and the vernacular, and her glazes are similarly of the most delicate and suggestive hues, recalling without reproducing those of the great east Asian traditions.

One of the other outstanding works in the exhibition is a bronze of the Prodigal Son (c. 1923) by Daphne Mayo, who studied at the Central Technical College with Lloyd Rees and later became engaged to him; they travelled to Italy in 1923-24 but for some reason she broke off the engagement in 1925, and never married. Her friend Vida Lahey, another Brisbane contemporary with whom she was close, also never married.

Rees, for his part, clearly continued to hold Mayo in high regard, for he gave this sculpture to the City of Brisbane in 1984 in memory of his friend, who had died in 1982.

Lahey, meanwhile, is represented in the exhibition by a fine still life with fuchsias and ginger jar (c. 1940), another of the rare works to demonstrate real mastery of the artist’s craft. There is also a striking portrait of Lahey by Mayo (1965), although the picture reflects certain unappealing and superficial stylistic features of its period.

Among the other paintings on the first wall, Caroline Baker’s portrait of a life class model, which appears on the catalogue cover, is an appealing if minor picture. Bessie Gibson’s La robe (c. 1920s) is a subtle monochrome portrait recalling the manner of Eugene Carriere. This and an attractive picture of a girl reading by Anne Alison Greene are the two portraits with the most intriguing sense of inner life.

There are a couple of pictures by Gwendolyn Grant, who had a generation earlier shared Vida Lahey’s studio. Fantasy (1943) represents a naked girl sitting on a beach looking out to sea, seemingly at a shadowy fleet of warships. It is a suggestive little picture, but somewhat careless in execution. A set of tiny landscape sketches on large gum leaves by Jeannette Sheldon are a bit kitschy in conception but more engaging than one might expect in practice.

The work of this period is on the whole fairly slight. There simply isn’t anyone with native talent comparable to Lloyd Rees, nor do they seem to have tried hard enough, to have pushed themselves to do better.

But at least they have some framework for making art; as the century progresses, what had formerly been more or less agreed standards of artmaking break down under the influence of modernism, and much of the resulting work becomes not only weaker still, but increasingly disoriented.

Looking back on the modernist movement today, over a century after its pre-war beginnings, we can see that the demolition of so many former rules and conventions, always celebrated in modernist propaganda as innovation, also had a darker side. Above all, it alienated art from the general public and reduced it to a specialist pastime of the wealthy and the cognoscenti. For the first time in history, the incomprehensibility of contemporary art became a running joke.

Perhaps less conspicuously, modernism also made art into the profession of stars. Of course the history of art had long been dominated by powerful, bold and inventive personalities, but there was also room for a second and third rank to produce respectable and even beautiful work, because that work arose from a collective tradition. In the new world of modernism, spectacular personalities like Picasso or Matisse, both discussed here recently, dominated the scene and there was little left for the second and third ranks.

Formerly these artists could at least be competent practitioners with moments of charm, intimations of mystery or glimmers of passion. Now, however, there was little that lesser talents could do but to follow in the wake of the dominant figures, turning their inventions into vapid cliches. Modernism, as we see here and elsewhere, was cruel to lesser artists, and of all modernist fashions, abstraction was the cruellest; a tiny handful of abstract painters, from Kandinsky or Mondrian to Pollock, have held their interest, while thousands of imitators have lost almost all claim to our attention. Leaving aside the abstract pictures, even the evolution of the portraits in this exhibition is telling.

Both Greene and Gibson’s portraits, already mentioned, achieve and yet go beyond literal likeness to suggest the inner experience of their subjects.

By 1948, Betty Quelhurst’s self-portrait is still interesting as an essay in introspection, but she is hampered by very weak technique. By 1952, Lola McCausland’s portrait of Dame Annabelle Rankin, probably largely painted from a photograph, conveys little or nothing of a living person. And by 1986 Caroline Baker’s portrait of lord mayor Sallyanne Atkinson has become almost childish in style.

With the decline of painting, it is not surprising that some of the more interesting work is in photography and video, even if these media are ultimately more limited in aesthetic scope. Tracey Moffatt’s image from the series Something More (1989), which borrows from the language of cinema and incidentally reminds us how much cinema has taken from the long tradition of history painting, remains an imaginative and subtly disturbing image, especially because it is open-ended and not prescriptive or ideological in meaning. In contrast, Fiona Foley’s Protector’s Camp is more burdened with overt ideological messages.

Some other works as well are too obvious in their social or political messages, so that a single glance is sufficient to see the point they are trying to make, and to realise that there will be nothing further to gain by giving the piece further attention. Others have the contrary fault: they say little as images, but rely on supporting texts to make claims on their behalf; but art must convey meaning in its own medium and with its own resources, not rely on extraneous justification.

Lyndall Milani’s film documents a performance made for the 10th Mildura Sculpture Triennial in 1988. The installation for the performance was an extremely elaborate one, including a pagoda and a pavilion joined by a reflective pool and lined with lanterns. In a longer perspective it would be interesting to consider this work within a history of the influence of Eastern spirituality on Western modernism.

Theosophy, with its oriental roots, had a fundamental influence on abstract painting in the first half of the 20th century, but a second wave of interest in oriental spirituality has developed in the last half-century, coinciding with the waning of conventional religious belief and the yearning for something beyond the sterility of consumerism and the society of spectacle, now updated and supercharged by the technology of social media.

Among so many works that fail to attract or hold our attention, there is one set of paintings by Sancintya Mohini Simpson to which we keep coming back, drawn by their enigmatic narrative content, at once vivid and reticent. As it happens, these works too come from the East, adapting the conventions of Indian miniature painting: and they remind us that artists need a culture and a language in order to be articulate.

Lloyd Rees, Museum of Brisbane, until May 20 ; New Woman, Museum of Brisbane, until March 15

The Museum of Brisbane, upstairs in the city’s imposing Town Hall, has two quite different exhibitions, one of which runs for another month and the other through to May. The conjunction of the two shows is fortuitous, but it turns out to be more instructive than one might have anticipated, one illustrating absolute clarity of focus and the other a general confusion about both the means and the ends of art.