Review, Peter Booth at TarraWarra Museum of Art

Painter Peter Booth evokes a world without sexuality, in which desire plays no part, and in which human consciousness has not evolved beyond the blind struggle to survive.

The third quarter of last century was the apogee of a teleological view of the history of art which broadly held that painting was destined to evolve towards flat pattern, abandoning mimesis, narration, imagery and, ultimately, even expression. The idea of history as a process with a predetermined end or destination was a Christian one, borrowed by Marxism. It was particularly adopted by American post-war writers trying to explain the phenomenon of American abstraction and to demonstrate that it was the necessary consummation of modernist art. Some of main individuals and arguments of the time are memorably satirised in Tom Wolfe’s The Painted Word (1975).

American fashions in art dominated both practice and critical writing in Australia in the same period, although with a time lag that left our painters in a constant state of anxiety about falling behind the latest models in New York; thus many were still doing gestural abstraction when the Americans had taken the final step of leaving gesture and painterliness behind in favour of the complete flatness of colour-field painting, in which areas of the composition could be marked off with masking tape and coloured in. Terminal flatness reached the antipodes later in the 1960s and its triumph was marked by The Field, the exhibition that in 1968 opened the new National Gallery of Victoria building on St Kilda Road.

Perhaps not surprisingly, this celebration of the end of painting, in the sense of its teleological fulfilment, was followed by the rise of new movements – conceptual, minimal, performance – that reacted against the commodification of art and asserted the actual death of painting. Naturally this was deeply disturbing to individuals who had previously imagined that they could carry on making and selling flat pattern works indefinitely. Some stopped painting. Others, like Dale Hickey and Robert Rooney, turned to conceptual art for a time before returning to their palettes after new movements asserted that the declaration of painting’s demise – and even conclusion – had been premature.

The most important painter in The Field, as has subsequently become clear, was Peter Booth, whose career is surveyed in an excellent and well-chosen exhibition at TarraWarra Museum of Art in Victoria. And in hindsight we can see hints that, even in 1968, there was much more and better to come. One of these hints is in the painterliness of his early abstractions – not yielding to the temptation of masking tape and spray paint – but the other is in the way he spoke of his works. Many members of this movement either gave their work generic or neutral titles, or else fanciful ones that implicitly supplement the bland surfaces with exotic literary associations.

Booth called his early paintings doorways, which implies a completely different way of imagining the pictorial surface and potential pictorial space. Many things have deep and archetypal associations for the human mind, from the sky, rivers and the sea to forests, open plains, light and darkness, but all of these are natural phenomena. Doorways, like houses, are human artefacts and, while doors are parts of houses and connected to the symbolism of home, they have an even broader range of symbolic association, since doors can be points of transition between any two dimensions, including life and death itself.

To think of what is ostensibly a surface covered in dense layers of black paint as, in reality, a doorway is at once to evoke the idea of closure, obstruction and blockage. It immediately questions what is beyond, why our passage is impeded, what sort of prohibition or dread lies behind the forbidden threshold. Either we are being locked out, prevented from proceeding on our journey, through the portal and into another phase of existence, or else something that cannot be faced is being shut in, suppressed and silenced.

As it happens, Booth was already making little sketches of his dreams and nightmares, a number of which are included in the exhibition; even while the paintings he exhibited were ostensibly rigorously abstract, the dream diary drawings hint at what lay behind the tense, obstructed doorways.

It is a whole world of vivid and even sinister imagery that could come out of any Freudian or perhaps, even better, Jungian collection of dream motifs. There are images of struggle, of fighting, of figures falling through the void or of a man drowning in the sea, but also, and perhaps most notably, of strange metamorphic bodies, part human and part animal or even insect.

The ancient metamorphoses recounted by Ovid come to mind, but even more specifically the transformation of Gregor Samsa into an insect in Franz Kafka’s Metamorphosis (1915), which seems to be recalled in several later paintings.

What helped this imagery to find its way into painting was in part the collapse of the flat-painting ideology and, in a couple of transitional works at the beginning of the exhibition, we can see the opaque surface literally breaking up before our eyes, although it is not yet clear whether what lies on the other side will be figuration. And then, quite suddenly, it is a rich and intensely evocative, symbolic or allegorical world of imagery that manifests itself, as though the doors had suddenly been flung wide open on to a strange and disturbing landscape of the mind. Booth made this transition through the close study of a number of great visionary artists of the romantic period, some of whose work is included in display cases in the exhibition.

In this first room there are engravings by William Blake – including appropriately enough Job’s Evil Dreams (1823-26) – and Samuel Palmer’s The Lonely Tower (1879). The spirit and aspects of the style of these artists are pervasive in three early works by Booth that hang nearby (all 1977): a tiny graphite drawing of a procession to a tower, with a landscape clearly inspired by Palmer, and two small but striking paintings: one of a tiny silhouetted figure striding across a desert landscape towards the setting sun, and another fiery landscape with a shadow figure and hieratic figures of a cat and a bird.

Nearby is the first of the large-scale visionary paintings in this exhibition: Painting 1978, whose deliberately neutral title leaves us to confront its dramatic imagery without commentary. Drawing on his own dream diary as well as Blake and, through him, no doubt on Dante, newly rediscovered by English readers in Blake’s time and the inspiration for an important group of watercolours in the NGV collection, Booth presents us with an infernal landscape of fire and livid light, in which one figure, perhaps an alter ego, stands with his back to us and the other faces us materialising monstrously in agony.

The infernal setting is less prominent but the sense of dread even more acute in the second room, representing the next phase of Booth’s development and one might say the maturation of his vision in the mid 1980s. Here, the central display case reminds us of another crucial source, the etchings of Goya, in whom Booth found a kindred preoccupation with nightmarish imagery, evocative of human violence and brutality. Goya’s buffoonish but threatening Simpleton (1815-19) seems to reappear as the blindfolded peasant figure of Painting 1981, with a demon perched on his shoulder, while in Painting 1988 he paints the insect-human mentioned above.

Here, as in the other works already discussed, the strength of the image derives not only from the horrifying and obsessive motif, but also from the simplicity and directness of the composition and design, and equally from the power of the brushwork. The paint is applied thickly, with a palette knife, with tremendous energy but, above all, with a sense of direction and purpose. This is what makes Booth’s handling of paint so entirely different from the heavy but inert impasto of Mandy Martin, discussed here a couple of weeks ago. There, the gestural paintwork seems unmotivated and directionless; here every mark is alive with intensity.

There are several other impressive pictures in this room, including Leadman (1986), in which a massive figure who seems to be made of the same inert material as the land and sky around him readies himself to fight an invisible and perhaps imaginary adversary, and Painting (2012), where a giant reptile with rudimentary human features crawls menacing through a bleak and apocalyptic landscape.

A peculiarity of Booth’s painting, incidentally, is that all of his figures, even when questionably human, appear to be male. This could be interpreted as a reflection on specifically male traits, but it is hard to make figures expressly male without a contrasting female presence; so it is better to take these figures as generically human. Booth’s world is one without sexuality, in which desire and eroticism play no part, and in which human consciousness has not evolved beyond the raw and blind struggle to survive.

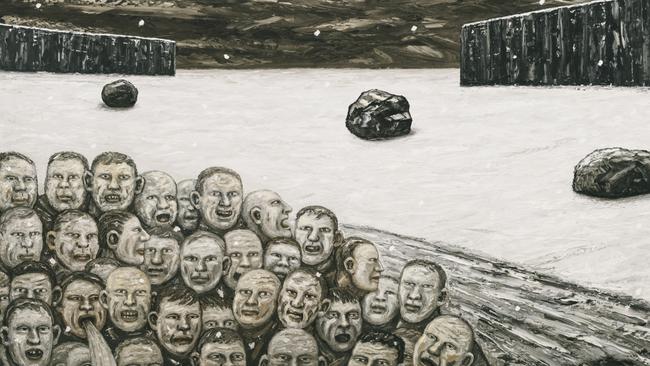

That struggle is most horrifyingly evoked in one of Booth’s best-known paintings, and indeed one of four images that I reproduced in my book Australian Painting from Colonisation to Postmodernism (1997): Painting 1982. The metamorphic man-insect is once again present in the background, while under his spell, as the exhibition label suggests, humans are tearing themselves apart in an orgiastic scene of cannibalism.

Most disturbing is what we can consider the central figure, for he alone opens his one remaining eye in uncomprehending horror, the first incipient awakening of inner life. He bears a certain resemblance to the central figure of Goya’s Third of May, 1808 (1814-15), and seems to be struggling into a primitive form of consciousness, dimly aware that his arms have been torn off by the predators gnawing them above his head.

The next section of the exhibition, in which Booth turns from figure painting to landscape, and from gruesome violence to the silence of snow-filled forests, seems to represent a new-found serenity. This is particularly the case in Winter (1993), which I well remember seeing when it was first exhibited. As the wall label points out, the reality may be somewhat more complicated, and the tone of the picture is certainly melancholy and elegiac. Wintry landscapes continue to appear in later years, sometimes with a bleaker tone, as in Painting (2008) or Painting (2014).

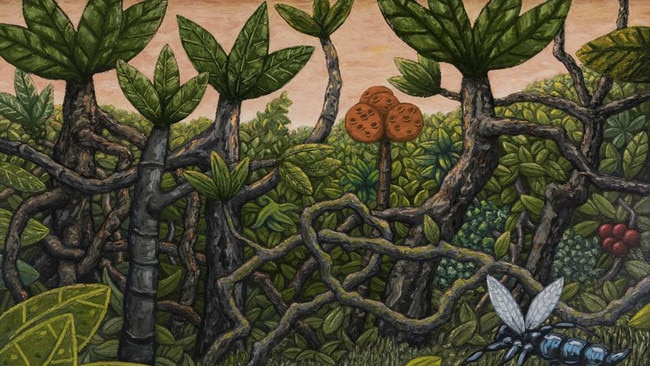

On the other hand the surprise at the end of the show, after these monochrome and solemn compositions, is to encounter a sequence of landscapes in an unfamiliar palette – not the fiery reds and oranges of the first period or the stark reds and blacks, alternating with leaden greys and muddy yellows, of the middle period, but now fresh, light and sunny colours and lush vegetation that together suggest tropical abundance.

Perhaps age has brought greater equanimity, after the tormented vision of the artist’s middle years. But even these pictures retain, whether in the presence of preternaturally large insects or in unusual effects of light, a note of tension and existential disquiet.

Peter Booth, TarraWarra Museum of Art, until March 13.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout