Religious refinement in Southeast Asian masterpieces

IT was good to rediscover the Art Gallery of South Australia, free of the Saatchi commercial octopus.

IT was good to rediscover the Art Gallery of South Australia, free of the Saatchi commercial octopus - and not surprising to read recently that the public response had been underwhelming - although weeks after its conclusion the half of the gallery the show had occupied was still empty and deserted.

Downstairs, meanwhile, the gallery's new exhibition could hardly make a greater contrast with the tone of the Saatchi show.

Beneath the Winds is a survey of Southeast Asian art drawn from the collection, including many recent acquisitions by donation or purchase, and accompanied by a thorough catalogue written by James Bennett, the gallery's learned Asian curator. To walk down the stairs into the exhibition space is to find oneself in a quiet and intense ambience, in coloured rooms hung with fine textiles, a world away from the shrill advertising and self-advertising of the works that filled this space on my previous visit.

Nothing, however, epitomised the difference more poignantly than a performance on the opening day of the exhibition by a gamelan ensemble accompanying a traditional Javanese dancer. Gamelan music is cyclical and hypnotic, with its repeated interweaving of the bell-like notes of bronze gongs and blades like those of xylophones; but the dancer was particularly captivating. She began to move with great poise, slowly, reminding one that the precise calibration of pace and even stillness are as important in dance as metrical rhythm, pauses and silences are in poetry.

There was no hurry, none of the frenetic or arbitrary movement that comes from the anxious desire to express oneself. She was completely present in every move she made and was exquisitely expressive while re-enacting centuries-old gestures and sequences of movement that are stylised and artificial yet based on the universal structure and articulations of human anatomy.

Such is the nature of an essentially traditional culture, in which the performer surrenders completely to inherited and learnt meanings and forms. Western art, since the Greeks, has valued innovation as part of a generally more dynamic and mobile sense of human life and history. But the role of innovation and of the individual needs to be - and is in the greatest periods of Western art - balanced against those things that give universality and durable interest to the work, that is nature and the web of inherited culture.

Beneath the Winds starts far away and thousands of years ago with the animistic cultures that preceded the arrival of civilisation in the Southeast Asian region, a world we explored in some detail a bit more than a year ago in discussing Life, Death & Magic at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra. One of the earliest pieces in the show is a simple stone pillar, roughly hewn into the form of an ancestor totem, reaching around to his belly, on which an erect phallus is a magical charm for the fertility of the tribe.

Religions came to these people as part of the package of civilisation, with more sophisticated, elaborate and stratified models of society, and for most of them civilisation came from India; Vietnam, on the east coast of Indochina, was influenced by its northern neighbour, China, but is hardly represented in the exhibition compared with the centres on the western side of the peninsula and further south.

Java was the first important centre in the region to our north; remarkably, most Australians are probably unaware that a significant civilisation existed so close to us, and there is probably a tendency to underrate the importance and interest of Indonesia. But one only has to visit Yogyakarta with the great Hindu site of Prambanan and the even more impressive Buddhist temple-mountain of Borobudur to realise that was indeed a great civilisation in this part of the globe more than 1000 years ago. Today, as we know, Hinduism survives mainly in Bali, while most of Indonesia has been Muslim since the 16th century.

One of the most beautiful items in the exhibition is a little golden statue of Siva from East Kalimantan (AD 8th-9th century), one of the three gods of the Hindu trinity: Brahma is responsible for creation and Vishnu for the preservation of the cosmos, which he sustains by sleeping. That is why he is represented in the world by emanations or avatars, the most familiar of which are Rama and Krishna. Siva is the god of change and destruction and renewal, so he plays a central role in the processes of life; in striking contrast to the exquisite and rare golden figure, he is also represented in aniconic (non-anthropomorphic) form by a stone lingam or phallus.

The phallus - here an example from 12th-century Cambodia - is a stocky pillar made up of three bands: a square one, an octagonal one and finally a round one on top. The sequence of forms, with the octagon as an intermediate form between square and circle, is familiar in Christian art as well (baptisteries are often octagonal in a symbolic system in which the square represents earth and the circle heaven), but here each band also stands for one of the persons of the trinity, implying that Siva, as a supreme deity, comprehends them all.

Cambodia was the next important centre - its great site of Angkor Wat is far better known to tourists than the Javanese temples - which initially assimilated Hinduism but later became (and has remained) Buddhist, following the conversion of King Jayavarman VII, who built the Bayon temple complex. The ancient Khmer culture of Cambodia in turn influenced Thailand, and all of these peoples developed forms of writing based on the ancient Indian Brahmi script.

Buddhism was not originally a religion in the teaching of the historical Buddha but inevitably became one, even to point of developing goddesses in emulation of the Hindu religion from which it emerged: for each of the gods of the Hindu trinity has a female consort who is integral to his power and efficacy. In China and Japan, the compassionate Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara was turned into the goddess Kuanyin (Kannon in Japanese). Here, however, we encounter the Buddhist goddess Tara, in a stone carving from Java that reveals, in her voluptuous Indian curves, her close affinity with the Hindu religious world.

Images of Buddha, like those of the principal figures of Christian religious art, vary considerably in iconography and style. In the first place, they may represent different moments in his life or different relations of the figure to the audience. Thus a gaunt and emaciated seated figure from Thailand is a copy of a famous ancient statue from the Hellenistic kingdom of Gandhara in what is now Pakistan, where Buddha was first represented anthropomorphically, and represents the period of his life when he practised asceticism before abandoning such extremes in favour of the middle way.

Other images represent him absorbed in meditation or in the position of calling the earth to witness, with one hand touching the ground, referring to the moment at the end of his temptation by the demon Mara when he calls the earth to witness the merits he has accumulated in the course of past lives.

Equally interesting is the stylistic variation in the form of the body and especially the face of Buddha in different cultures and a different times. The body of the Buddha, originally borrowed, in Gandhara, from the youthful figure of Apollo, evolves into forms that are now soft, rounded, even corpulent, now slim and elongated. What is constant is an asexualisation, indeed a feminisation of the figure, symbolic of the neutralisation of appetite and desire.

Within the range of common elements, there is further room for nuances of spiritual expression that are also characteristic of the temperament of the various cultural groups. Thus the Khmer faces are broad, serenely but distantly smiling and still. The faces of Thai Buddhas are longer and pointier, have sharp features and are generally more highly strung; one assumes the tone of Buddhist meditation in Thailand must differ correspondingly.

One of the things that is notable about the adoption of the new religions in these countries is that they seldom entirely abolished the earlier animistic beliefs. Further to the north and beyond the area covered by this exhibition, Japan is the most sophisticated and elaborate case of this phenomenon, for Buddhism and Shinto, which grew out of more primitive pre-Buddhist beliefs, coexist as parallel or rather complementary systems of belief that pertain to different parts of life.

In Southeast Asia, as so often elsewhere, animistic beliefs persist in relation to death and the rituals for dealing with dead bodies, and in everything to do with the fertility of the earth and of men and women, whereas higher religions, as they are known, deal with ethical behaviour, spiritual practice, wisdom and holiness, and ideas of salvation in the next world. Thus while figures of Buddha evoke spiritual meditation, most of the objects connected to animistic belief relate to death and funerary customs, including substitute bodies for the deceased, and even puppet mourners.

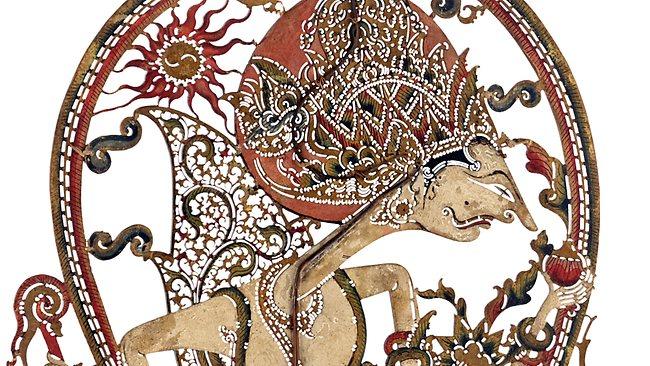

Some religions are more tolerant of the survival of primitive practices than others, and the least tolerant are, as usual, the three monotheistic religions: Judaism and its offshoots Christianity and Islam. Islam has dominated the area covered by Malaysia and Indonesia for the past four centuries or so but fortunately, historically, it has tended to be more liberal in countries farther from the Arabian epicentre of the religion. The result is that, although Islam has made little if any positive contribution to the arts in Indonesia, it has at least not extirpated its rich traditional culture, which continues to be inspired by Hinduism: the music, the classical dance and mask theatre, the wayang kulit shadow puppets. In Europe, too, much art continued to be inspired by the theoretically obsolete Olympian religion, but this was overshadowed by the vast amount of work in all media devoted to Christian belief.

But while Hinduism survives largely in the field of culture, the earlier animistic beliefs are more tenacious and no doubt still stubbornly held by many Southeast Asian Muslims. Thus, although more than 100 years old, one of the most surprising displays is a pair of carved wooden figures in the Muslim courtly dress of the time - bearing in mind that figurative art is theoretically forbidden by Islam - representing the crop goddess Dewi Sri and her consort. Her name comes from the title of Vishnu's female companion Lakshmi, but she is evidently a later incarnation of a very early goddess figure, and the pairing recalls the ancestor couples found from time immemorial through the whole Southeast Asian region, revealing yet again how, even under a new dispensation, successive layers of belief are superimposed in a complex palimpsest.

Beneath the Winds: Masterpieces of Southeast Asian Art, Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, to January 29.