Reflections on the icons of Christian art

Michael Galovic was in awe of the frescoes in churches of his European childhood. His work is now in more than 100 churches here and abroad.

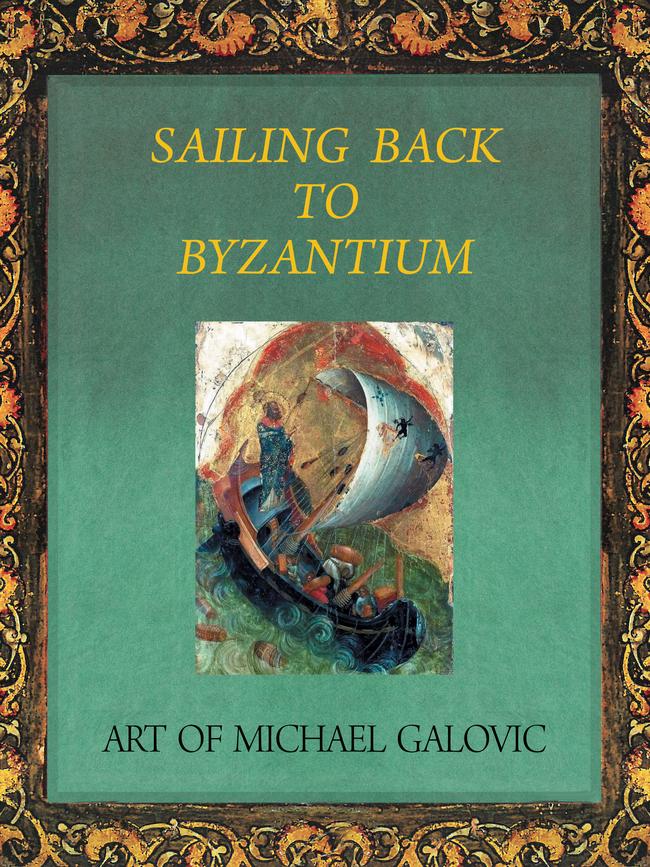

Michael Galovic’s status as Australia’s leading religious artist is cemented with the release of new retrospective, Sailing Back to Byzantium. The lavishly produced collection from Yarra & Hunter Arts Press covers the last 17 years of his artistic career. Profoundly enjoyable as an art object in its own right, suitable even for prayer and meditation, the monograph is a gift to the reader seeking a deeper understanding of both iconography and contemporary art, as it contains extensive reflections from the artist and a host of knowledgeable interlocutors.

It deserves to be read by any person interested in the living tradition and possibilities of Christian art.

Sailing Back to Byzantium is first and foremost a showcase of the iconographer’s art. Galovic is committed to the most rigorous traditional methods, developed during his years as an art student in Belgrade and in an apprenticeship to his stepfather, under whom he learned how to restore icons that were whitewashed under communism. In scores of icons, he combines ancient methods with a painter’s gusto. He refreshes iconography with personality, and refuses to be reduced to a mere stenographer of established forms. Beloved by Catholics and Orthodox alike for his boldness, Galovic’s icons appear in churches and institutions across Australia and the world, including the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem’s Co-Cathedral. As a compendium of iconography, Sailing Back to Byzantium is an education in and of itself.

Yet Galovic is not solely, or strictly, an iconographer. Rather, he is Australia’s primary Christian participant in the reaction to the depletion of 20th century modern art, for whom the American critic Suzi Gablik was the leading theorist in Has Modernism Failed? (1984) and The Reenchantment of Art (1991). In Gablik’s view, modern art began with aspirations of liberation but became “a tradition of revolt gone sour”. After exhausting itself in the desert of postmodern irony, contemporary art found itself bereft, “at odds with systemic wisdom and equilibrium,” Gablik thought.

In the Neo-Expressionism of the 1980s and 1990s, with its self-conscious return to the sacred as a paradigm of recovery, Gablik saw tentative signs of the renewal in art of consolation, connection and harmony. Many of Galovic’s works remind the viewer of the leading lights of Neo-Expressionism – his Christ and All Saints (2017), Rich Harvest: Christ and His Disciples (2008) and other works recall Georg Baselitz’s Adieu (1982) with their tessellated square backgrounds upon which the consoling figura Christi is depicted. But he also honours more ancient debts, especially to the proto-Expressionist El Greco.

As the artist notes, icons seem deceptively simple to the viewer, but are almost preternaturally complex for the artist to execute; one reason why the iconographer reproduces the masters’ works even after he becomes a master himself. Galovic applies this norm of iconography to the modern masters, reproducing their styles in his own pieces – such as Gauguin’s Yellow Christ (1889), in his Yellow Christ Resurrection Triptych (2013). He allows the modern masters to speak while permitting the spiritual power of the icon to subsume their angst within its more stable and peaceful frame. In doing so, he nullifies the latent iconoclastic tendencies within modern art, pressing modernity instead into an uneasy and provocative witness to Christ.

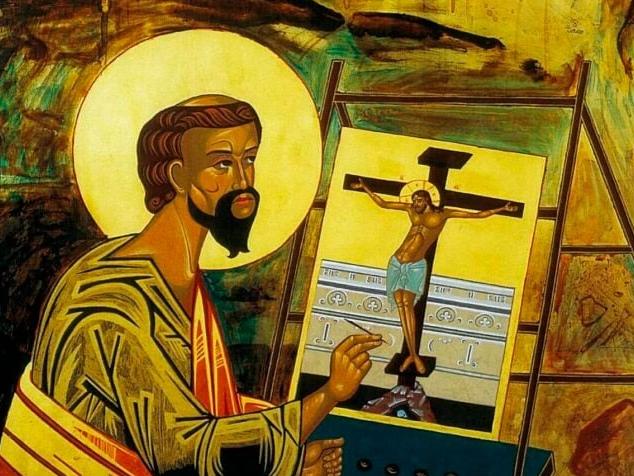

The artist’s most convincing and technically interesting works are therefore his pastiches of icons and religious artworks with modern paintings. In one emblematic work, St Luke Painting the Crucifixion (2004, and Blake Prize finalist), Galovic playfully approaches irony – a forbidden mood in iconography – without trespassing in its negative territories. St Luke depicts the iconographer’s “reverse perspective,” as the theologian Paul Evdokimov described it. The Crucifixion, depicted in a seared and bereft Cubist style reminiscent of Picasso, is reproduced picture-in-picture by St Luke as a sacred icon.

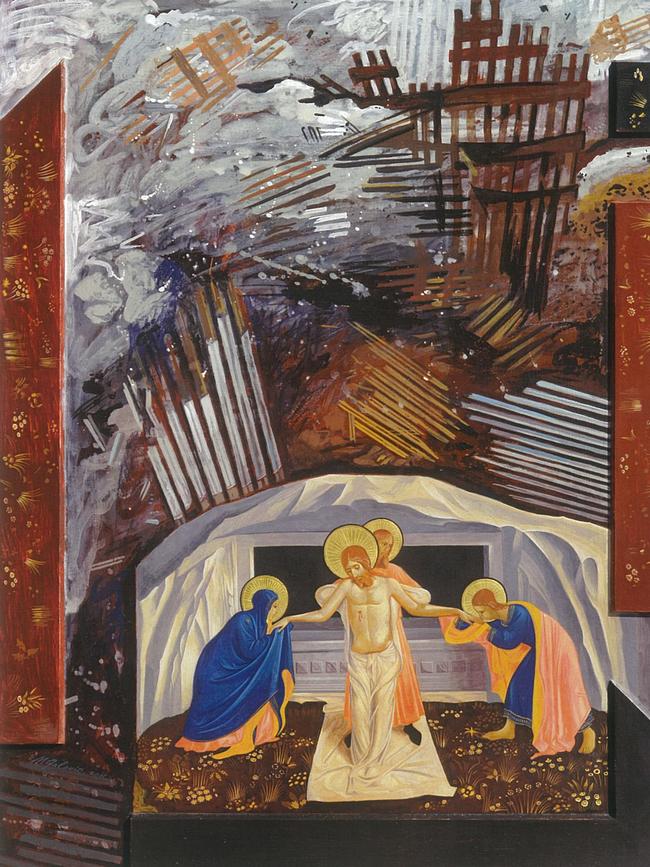

In this impossible scene we have in miniature an affirmation of the enduring power of sacred sight to transform modern disintegration. Present also is a gentle critique of eastern art’s formalism, which turns deliberately away from the bloodied, writhing Christ of western (and modern) art to depict him ruling in tranquillity from his throne, the Cross. Similar themes can be seen in his September 11 Series/Homage to Fra Angelico, in which Christ rises from the tomb in the old master’s style, against the backdrop of jagged, crumbling wreckage from the Twin Towers.

Galovic draws on another significant theme of re-enchantment, the natural world, in artworks inspired by Indigenous Australia. His Uluru series plays on the icon’s depiction of the divinised human and extends it to the personhood of non-human beings. He paints Uluru in the iconographic style, illuminated with gold leaf, as if the great rock were a glorified saint; a confident gesture to the Indigenous Christian theology of the indwelling of the Holy Spirit in country. Whether one wishes to go all the way with Galovic here, he shows the artist can be both provocateur and agent of reconciliation. Mervyn Duffy is surely right to describe the artist’s Indigenous-inspired works as a kind of “Jesus Dreaming.”

But nature is a minor theme in Sailing Back to Byzantium. Galovic’s brush has remained steady over the subject in more need of spiritual renewal, the human person. In his quartet of Marian panels – in my view the most interesting works in Sailing Back to Byzantium – Galovic foregrounds the shining figure of the Mother of God against expressive backgrounds of clashing colour and movement, passionate fragments and explosions, and cosmic disintegration. If in St Luke he presents the sacred as a perspective that remains viable for (and against) we moderns, here the figure of Mary – humankind’s gift to God at the Annunciation – shows the person held together by grace and the declaration of the Gospel.

In artworks too numerous to appraise here, Galovic’s contemporary art speaks emphatically to our spiritual craving for wholeness amid life’s fragmentation. In this respect, it is more moving than his more formally complete traditional icons – wonderful and technically proficient as they are. This may explain his enduring dialogue with Picasso, the artistic protagonist of last century’s anxiety. In his Resurrection Triptych (2020), the influence of Picasso can clearly be seen in the central image of the “broken Christ,” in which spears thrust upwards menacingly into the sky above the deposed spiritual body of Christ, plunged into a Hades painted in Cubist fashion – brown, indeterminate and desolate. The painting comments on “war and defeat … the bleakness of destruction,” as Galovic’s student Kerry Magee writes. Admitting such a perspective into sacred art testifies to Galovic’s faith in contemporary Christians’ capacity to grapple with complicated themes. The triptych is hung at an ordinary Catholic parish in Rosemeadow.

It is no mean feat for the artist to cherish the sacred after it was “reduced to rags,” as Gablik wrote. Galovic is consequently an artist for all seasons: contemporary and ancient, eastern and western, Australian and European, an established painter in his prime and a perennial student of the masters. His confident occupation of competing artistic polarities is perhaps why Catholics are such enthusiastic adopters of what might otherwise be coded as eastern art.

Eastern Orthodox Christians often unfairly claim that modernity is an intrusion from a fallen western world; for Catholics, modernity is a dispute within the household of the west. Art and theology dwell together, and as westerners unpick the tangle of modernity’s legacy we must also come to terms with our affection for (and revulsion at) modern art. Galovic is truly an elder for Australian Christians insofar as he knows the paths through this tangle, and can lead others through it. Sailing Back to Byzantium is not only a rich and enjoyable retrospective, but a map of this artistic terrain, and is a major landmark in the history of Australian religious art.

Adam Wesselinoff is editor of The Catholic Weekly; this is an edited version of an essay first published in The Catholic Weekly in July.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout