MONA’s Heavenly Beings asks big questions of art and Christianity

The Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart has enjoyed juxtaposing the ancient and the contemporary since its inception, but this is its first exhibition devoted entirely to old art. But does it work?

The Museum of Old and New Art in Hobart has enjoyed juxtaposing the ancient and the contemporary since its inception, but this, as the press release points out, is their first exhibition devoted entirely to old art; to the religious icons of the Byzantine Empire and the Greek and Slavonic worlds in which Orthodox Christianity has survived since the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

But these icons, especially because they are primarily meant to evoke the heavenly beings of the exhibition’s title rather than to represent anything actually seen in the world, raise fundamental questions about the very nature of images. How can we define the differences between what we consider, in a commonsense way, as naturalistic, stylised or expressionistic renderings of phenomena? How and why do different approaches prevail in one period or another or within various cultures and systems of religious belief?

Such questions are even more important today, when new technologies have radically transformed our relation with images. For a generation or so, we have been able to call up pictures of almost any famous work of world art on our screens; this has been a wonderful thing for those interested in the subject, but like everything on the internet, the ostensible ease of access is deceptive and only meaningful or useful for those with the knowledge to understand what they are seeing.

At the same time, and even more conspicuously, contemporary life is stupefied by the unrelenting assault of imagery, mostly photographic in origin; the vast majority of this imagery has been digitally enhanced for years, but we are now at the beginning of a new wave of unreality, with images produced wholly by AI. Meanwhile children in most schools are no longer taught to draw or paint in a representational way: as humans increasingly lose the primary ability to make our own images, machines will produce ones designed, like junk food, to appeal to our cravings.

The artists who produced the religious icons of Heavenly Beings worked within a pictorial tradition that was tightly regulated by religious principles, and within a set of conventions so conservative that practitioners today produce images that differ little from the works of centuries past. This tradition, however, had much older roots in a millennium or so of ancient Greek and Roman painting that preceded the rise of Christianity in the latter centuries of the Roman Empire.

It also had a future, for the mature Byzantine style represented in Italy in the mosaics of San Marco in Venice or of the Palatine Chapel in Palermo and later the relatively more naturalistic work of Giotto’s master Cimabue, became the starting-point for the history of modern art. But Giotto’s new interest in space and volume, and his emphasis on painting figures as though they belonged to our world, represented the reversal of the process by which Byzantine art had evolved in the first place.

Byzantine art developed, in other words, by eliminating many of the naturalistic features of ancient painting, the very features that Giotto was to rediscover in the 14th century. The motivation for this was scriptural: the Second Commandment prohibits the making of “graven images” and especially their worship; this injunction had been disobeyed even before it was pronounced, for it was as Moses came down from the mountain bearing the Ten Commandments that he discovered the people of Israel worshipping the Golden Calf.

Thenceforth, the Jews observed the prohibition of images exceptionally strictly, as did most of the Moslems. But the Christians, living with the abundance of painted and sculpted imagery of the Greek and Roman worlds, could not wholly abandon their old habits. The Catholic Church in effect simply ignored the prohibition of images, and in Christian scriptures the Second Commandment is often merged with the First. During the Reformation, on the other hand, many Protestants were violently iconoclastic and churches were purged of paintings and sculptures in areas under their control.

The Orthodox Church had been afflicted by long periods of officially-sponsored Iconoclasm – literally “icon-breaking” – in the eighth and ninth centuries. This was the time of the rise and spread of Islam and the new anxiety about images has often been attributed to Islamic influence, or the fear that God could be favouring the Moslems because of their fidelity to his laws.

In any event, the supporters of the icon tradition – or Iconodules – eventually prevailed, but the long-term effect of the anxiety about graven images was the choice to make iconic images deliberately flat, largely avoiding modelling and the suggestion of real space. The composition of an icon and even the shape of the Virgin’s face were subject to regular geometric conventions. Interestingly, the Persians too refused to give up images, at least of secular subjects, but similarly adopted a convention of flatness, even though their figures are highly animated and set in luxuriant and elegant natural settings.

The canon of subjects in icon painting is also governed by strict conventions, as are sacred subjects in all religions. The eastern canon naturally overlaps with that of the Christian church in many respects, but also includes some themes that are less common and others that are almost never seen in the west.

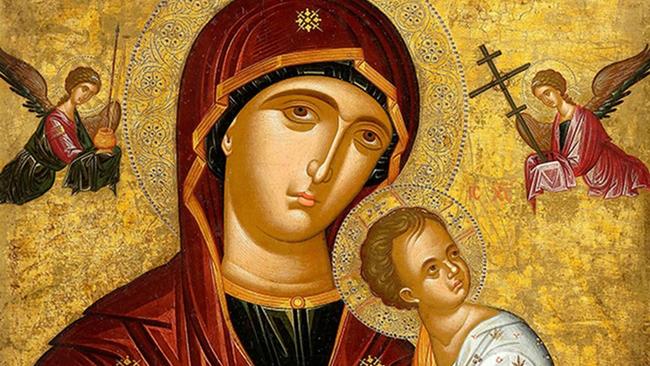

Among the most common subjects are, not surprisingly, the Virgin and Child and the Crucifixion. In the former, the Virgin as Theotokos, the bearer of God, is always treated with a combination of sobriety and sweetness; her face, as in devotional images of her in the west in the pre-Renaissance and early Renaissance periods, was the most important part of the whole painting, because these images were designed to be the focus of religious meditation and prayer, and the eyes of the worshipper would be fixed on those of the Virgin whose aid he was imploring.

Another crucial scene is of course the Crucifixion, in which most elements will be familiar at least to those who are acquainted with early Italian painting. One of the most important motifs is the skull that appears at the foot of the cross; this is the skull of Adam, and reminds us both that Adam brought into the world the Original Sin that Christ has come to redeem, but also that the very timber of the Cross has grown from an acorn planted with Adam’s burial. The skull appears in many early Renaissance paintings, but the whole story is told in Piero della Francesca’s Legend of the True Cross in San Francesco in Arezzo.

Somewhat less familiar, although a regular motif in early Italian paintings of the Last Judgement, is the episode known as the Harrowing of Hell. According to tradition, after the Crucifixion on Good Friday, Christ descends to the Underworld where he releases the souls of the virtuous figures of the Old Testament, before the Resurrection on Easter Sunday. The iconography of this scene usually includes Christ trampling on the fallen gates of Hell, and helping Adam and Eve to climb out, while all around we recognise Abraham, Moses, David, Solomon and others.

On the other hand, there are stories that are well-known and widespread in the Eastern tradition – in medieval frescos in Cyprus, for example – but which are almost completely foreign to the Western Church’s canon. One of these is the story of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste; according to legend, 40 Roman soldiers who had converted to Christianity were condemned in 320AD to be left to die of exposure, naked on a frozen lake in the middle of winter. A warm bathhouse stood nearby to tempt them to abandon their faith; only one did so, but he was replaced by a guard who was so overwhelmed by the men’s courage that he stripped off his clothes and went to join the men.

Similarly, while there are some individual saints whose iconography we recognise at once – Saint George on horseback, for example – there are many saints of the Eastern Church who are virtually unknown in the west and hardly ever appear in Italian art. One thing that helps us to identify these unfamiliar figures, however, is the fact that icons are commonly inscribed with the names of the saints represented, even when they are as universally known as the Virgin Mary herself.

The inscription, in Greek or later in Church Slavonic, is generally abbreviated and thus not particularly easy for the layman to interpret. But they remind us of the way that these deliberately flat images are far more compatible with writing, since the image is on a surface, like a page, rather than implying real space. For the same reason, writing harmoniously accompanies Chinese and Persian painting, but always feels like a label stuck onto the surface of a modern Western picture.

The flatness is not absolute, however, especially as most of the icons in this exhibition belong to the period after the fall of Constantinople, when the Byzantine tradition of painting was increasingly subject to Italian influence. Many of the best works, in fact come from Crete from the 15th to the late 17th centuries. After the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453, Crete remained under Venetian rule until it too was finally conquered by the Ottomans in 1648-69, after a 21-year siege of the capital Candia, the modern city of Heraklion.

This meant that Crete was effectively only ruled by the Turks for two centuries, until they lost their grip on the island in the later 19th century. Especially during the 200 years between the fall of Constantinople and the siege of Candia, Crete thus became the bastion of authentic Byzantine Greek culture, including scribal practice; when, in the last quarter of the 15th century, Greek fonts for the newly-invented printing press were produced, they were modelled on the handwriting of Cretan scholars.

On the other hand, because of this very connection with Venice, a city that itself had long connections with Byzantine culture, Cretan artists were inevitably exposed to the new naturalism of the Renaissance. The most famous example of this cultural exchange is the 16th century El Greco, whose real name was Domenikos Theotokopoulos, who had been trained in Crete as an icon painter before joining Titian’s studio in Venice and later taking his unique and expressionistic style to Spain.

But even the more traditional painters who carried on an unbroken studio tradition in Crete were clearly drawn to model and animate their figures to varying degrees in the new Italian style. Often, and understandably, this occurs more with the smaller and peripheral figures than with the greatest and most holy, whose hieratic stillness was inseparable from their function as effectively portals into another and transcendent world; as W.B. Yeats wrote, evoking Orthodox icons in Sailing to Byzantium (1927):

Once out of nature I shall never take

My bodily form from any natural thing …

-

Heavenly beings: Icons of the Christian Orthodox World at MONA, Hobart, to April 1

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout