Queensland art show from the Met a religious experience

There is so much to say about this remarkable exhibition of masterpieces from the Met at QAGOMA in Brisbane.

There is so much in this remarkable exhibition that it is impossible to do it justice in a short column so, as I have done for a few other shows of this scale, I will talk about a selection of paintings from the earlier centuries this week and the later ones in the next week or two. Even so, it will be impossible to include all the things that deserve attention. I should add that all of these works can viewed online at the Metropolitan Museum website, with high-quality images and insightful, accurate commentary.

We may start with an early Crucifixion (c. 1420-23) by Fra Angelico, several years before Masaccio’s work at the Brancacci Chapel. The figures do not yet have the solidity and firm stance that Masaccio introduces, but they are full of closely observed details and brimming with psychological life: there is a particularly interesting play of glances between the various characters. In the foreground, Christ’s mother Mary has fainted from grief; she is attended by two holy women and Mary Magdalene in scarlet, while John, in blue and pink, weeps at the foot of the cross; the skull is that of Adam, whose original sin is redeemed by the death on the cross.

Nearby is another small painting, Giovanni di Paolo’s Paradise (1445), inspired by part of Fra Angelico’s Last Judgement (c. 1631), but the Sienese painter ignores the Florentine innovation of perspective in favour of an imaginary, tapestry-like space in which figures stand above rather than behind those in front of them. The composition is full of Dominicans, including Saint Dominic and Saint Thomas Aquinas, since the painting was part of a commission for that order, as well as other recognisable figures, such as Saint Augustine with his mother Monica in the centre. But above all Paradise is imagined as a place where those who loved each other in life – whether as parents, friends or lovers – will be reunited in joy.

The world of Piero di Cosimo’s Hunting scene (c. 1495-1500) could not be more different. Piero, a complex and reclusive artist, is inspired by the Latin philosophical poem De Rerum natura, rediscovered in 1417 and first printed in 1473, in which its author Lucretius gives a comprehensive Epicurean and materialistic account of the world. One of the objects of the Epicureans was to banish the fear of the divine by demonstrating that the gods have no role in nature and take no interest in our conduct.

In this picture and its companion, The Return from the Hunt, also at the Met, Piero ponders the life of primitive man, as yet barely distinct from beast and still living in the company of fauns and centaurs. The forest fire raging in the background follows Lucretius’s suggestion that early humans used fire to drive animals out of the woods and kill them, but it also acts as a metaphorical image of the extreme violence of the hunting and killing in the foreground.

Even animals attack each other in the frenzy, and on the lower right a dead man reminds us that we are not always victorious in the contest.

Death and hunting are again associated, but only by implication, in Titian’s Venus and Adonis (1550s), a subject of which Titian and his workshop produced many variants.

The immediate source of the story, as often in the renaissance, is Ovid’s Metamorphoses, a poetic compendium of mythology linked by the theme of transformation, but its origins are much older. The goddess is shown trying to dissuade her young lover from going to the hunt, where he will be killed by a boar.

The strange but memorable attitude of Venus is borrowed from a minor antique relief of Cupid and Psyche (the figure of Cupid seems to have inspired Michelangelo’s figure of Christ in the Pietà and, through this work, David’s Death of Marat).

But the psychological tension of the composition is between the clinging female body and the active, departing male one, momentarily joined by an intense but ambiguous meeting of the eyes; while the pictorial magic arises from Titian’s miraculous union of colour and tone, and his execution of the whole picture, figures and background, from almost the same palette.

Love is Caravaggio’s theme too in one of the most important of his works to have been seen in Australia, albeit an early one, The Musicians (1597), which I last saw in the outstanding Caravaggio exhibition at the Scuderia del Quirinale in Rome in 2010 (reviewed here at the time). The picture was painted for Cardinal del Monte, one of the first to recognise the artist’s talent, and includes what is generally accepted to be a self-portrait – the swarthier figure in the background, shown playing a cornet.

Although it would be anachronistic to call Caravaggio homosexual (or even bisexual), since such a category did not yet exist and the artist had relations with women as well, many of his early works are undeniably homoerotic and he seems – interestingly in view of Freud’s ideas about narcissism – to have been attracted to boys who looked rather like himself. Here the connection is with the lutenist (possibly, as Keith Christiansen suggests, a castrato), and the cupid on the left binding together light and dark grapes is probably an allusion to the union of dark and fair; there is even a formal allusion in the way the two heads tilt towards each other. And the union of opposites was at the same time a familiar conception of musical harmony.

Two paintings by Rembrandt and Vermeer also have an allegorical character, and yet one is complex, explicit and programmatic, while the other is mysterious and hard to pin down. Rembrandt’s late Flora (c. 1654) catches our attention by its very awkwardness, the unusual profile view of the head at right angles to the torso. Titian’s Flora (c. 1515), which the artist could have seen in Amsterdam, has been cited as an inspiration, but her frontal torso is more harmoniously matched with a head seen in the normal three-quarters view. Rembrandt, however, is probably referring to a profile drawing of his wife Saskia, who had died in 1642; Orpheus-like, he conjures her back to life as the symbol of springtime and renewal, and yet she forever gazes away into the distance, and this is what imbues the painting, in spite of its ostensibly happy subject, with a mood of solemnity and sadness.

Vermeer’s Allegory of the Catholic Faith (c. 1670-72) uses a familiar device, the foreground curtain, to lead us into an interior space, here imagined as a private chapel, since public celebration of the mass was illegal at the time in Protestant Holland. The composition is filled with a repertory of religious symbols, from the chalice, reminding us of the doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the bread and wine of the Eucharist, to the apple on the ground recalling original sin. But Vermeer’s acute sense of literal reality is such that we feel as if we are looking at an elaborate mise-en-scène which never turns into a spiritual vision as in Italian baroque paintings.

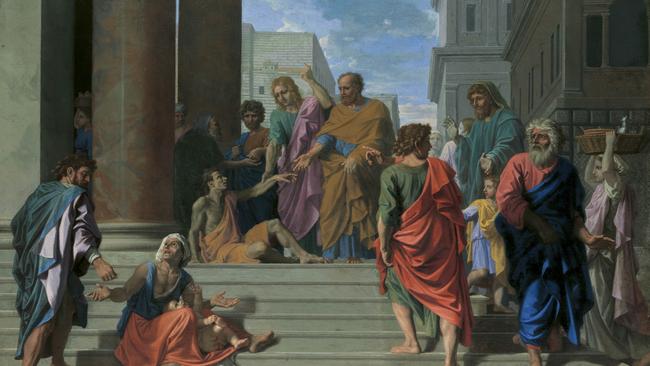

One of the most important paintings in this exhibition, and again one of the most significant works by this artist to have been shown in Australia, is Nicolas Poussin’s Saints Peter and John Healing the Lame Man (1655). As the museum notes, this is one of three great cityscape subjects painted at around the same time, the others being Christ and the woman taken in adultery (1653) and The Death of Sapphira (1654), both of which are in the Louvre. All of these works reflect a renewed meditation on Raphael, partly because two of them are drawn from the Acts of the Apostles, illustrated by Raphael in the Cartoons (Victoria and Albert Museum).

More deeply, however – and as I discussed at greater length in French Painting in the Golden Age (Thames & Hudson 2003) – Poussin is here concerned with the action of what Christians would consider the Holy Spirit (pneuma hagion) and what he, in his more syncretistic and philosophical perspective, identified with the Stoic Logos, the reason or spirit that governs the cosmos. This Greek philosophical term had already been used by St John in the opening of his Gospel: “In the beginning was the Word.”

The other two paintings mentioned demonstrate the power of the Word to redeem in the first case and quite literally to bring death in the second (Sapphira’s death is the consequence of her lie); and here, in the first miracle of the Apostles after Christ’s death, Peter discovers that he, too, can become the instrument of the Word or Logos and heal a cripple, while John points to the celestial original of their power.

But there is more. It may seem strange that this important subject is dwarfed, in the middle ground, by apparently secondary figures in the foreground; but that is because they are not secondary after all: there are no accidents or oversights in Poussin’s work. Look at the costumes: Peter is wearing the blue and yellow which are his standard colours in iconography; the young man on the right is wearing green and red, which are the colours of Saint Paul, and the point is made more emphatic by the overlapping of his figure with that of Peter.

This young man must be Saint Paul, who first appears as Saul a few chapters later in Acts, initially as an enemy of the Christians, before his famous conversion on the road to Damascus. But it is typical of Poussin’s originality – as we see in his mythologies too – to adopt a more philosophical interpretation of the story: the real action of the Logos in this picture is not merely in healing the cripple, but in taking possession of the mind of Saul, who points towards the miracle while the old man on the right, departing with an appalled expression on his face, represents the mind that is impervious to the Word and remains trapped in darkness.

Thus this picture could perhaps better be titled The Conversion of Saint Paul, something which seems to have escaped all other Poussin scholars until now, and which I had not realised until I studied the picture closely in Brisbane.

And there is yet more: we may see in the figure of Paul an allusion to justification by faith, while the balancing figure on the left, giving alms to a poor woman, stands for justification by deeds; but in a final example of Poussin’s extraordinary originality as a philosopher-painter, the focus is not on the giver of alms, who appears almost distracted, but on the recipient of the charity, who seems to experience a kind of epiphany as she receives not a material gift but the Word itself.

European Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gallery of Modern Art, until October 17.