Recovered memories in the photographs of Bernhardt Holtermann

IMAGINE the discovery, in 1951, of an archive of 3500 glass plates from the 1870s that had lain undisturbed for 80 years or so in a Sydney garden shed.

A GREAT-AUNT dies and you find among her effects a leather hatbox, itself an artefact almost Edwardian in age.

It is filled with photographs, mostly of the small format commonly used for family snaps between the world wars or even earlier, a century ago. One after the other you pick up shots of gentlemen in suits and wing collars, ladies in long dresses, groups at weddings or funerals, men in shirt sleeves displaying a catch of fish, shots of somebody in Venice: but who are they? Presumably further aunts and uncles and cousins, more distantly related, but whom you will never be able to identify.

It is the pathos of photography always to be a record of the past, locked into a specific moment as a drawing or painting is not. Photographs, since the beginning, have been mainly used as an aid to memory - more dangerously as a substitute - but in themselves and alone, as in the great-aunt's hatbox, they are like the memories of someone who has sunk into dementia, and whose recollection of their life has degenerated into a random succession of unlabelled images.

Imagine then the discovery, in 1951, of an archive of 3500 glass plates from the 1870s that had lain undisturbed for 80 years or so in a garden shed in Chatswood, on Sydney's north shore, with nothing to identify the subjects or locations of the pictures. But fortunately there was one name that could serve as a starting point for the process of recovery and identification, which was then pursued by Keast Burke, editor of a publication called the Australasian Photo-Review, for the next 20 years.

The pictures had all belonged to Bernhardt Holtermann, a German who had come out to Australia in 1858 to avoid military service and had turned to prospecting for gold. After years of digging he was rewarded with an enormous find and became an instant millionaire; in the process, he also discovered the largest nugget of reef gold seen - 286kg - thus becoming not only rich but famous. Holtermann knew the sheer size of his nugget had an almost mystical potency as the symbol of every miner's longing and took care to have himself photographed with it repeatedly; it was named for him and became, as we may say today, the core of his brand.

The plates were in the possession of Holtermann's daughter-in-law and were donated to NSW's Mitchell Library in 1952 by his grandson and namesake, Bernhard Holtermann. As it was known that he had made his fortune in Hill End, 275km from Sydney, this narrowed down the search for locations, and many of the pictures are of that town in its brief gold-rush heyday; others eventually turned out to be of Gulgong and other smaller locations in the same area. Further pictures of Sydney, Melbourne, Ballarat and other cities naturally were much easier to identify.

It turns out Holtermann used some of his considerable fortune to sponsor a photographic campaign that ultimately was intended to result in an international exhibition that would encourage more people to migrate to the new land. The photographers he employed were the picturesquely named Beaufoy Merlin and his younger assistant Charles Bayliss, whose business was named the American & Australasian Photographic Company.

Merlin was a documentary photographer and entrepreneur who had a strikingly original business idea that has also created an invaluable resource for historians. He would travel from town to town, systematically taking photographs of all their buildings; as a company advertisement claimed in 1870, he had "already taken photographs of almost every building in Melbourne, as well as in every town of any importance in Victoria". The negatives were held in the Melbourne office, and reproductions could be ordered by mail.

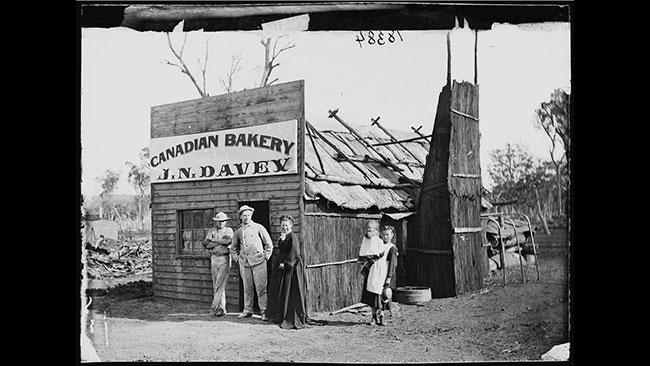

What made this unique project doubly interesting was that Merlin would have the people who lived or worked in each building come outside and pose for the camera in front of their house or workshop. The result is not simply an architectural but a sociological survey, complemented by the studio portraits of those who wanted a more formal picture of themselves - though perhaps not surprisingly the studio pictures are often stilted and uncomfortable, especially in contrast with the spontaneity of the street scenes.

The quality of the wet-plate or collodion process of photography allows the images to be enlarged almost indefinitely. Digital images, as we know, are converted into data and depending on the degree of resolution - basically how big we are willing to make the data file - we find the image eventually will decompose into pixels as we zoom in. An analog photograph, though, is not made up of a finite number of data but is a continuous fabric, an imprint of reflected light that can be opened up to reveal details invisible at first; this was the premise of Michelangelo Antonioni's film Blow-Up (1966).

The images in the exhibition (now also online on the State Library of NSW website) are displayed in enlarged form or, even more suggestively, on digital screens, demonstrating the process of enlargement before our eyes: the revelation of detail, as faces appear in the crowd, and expressions on faces, as signs and posters become legible and windows open up to reveal displays of bread or meat, household implements pinned neatly to a board, is deeply mysterious, and akin to the return of lost memories under hypnosis or in the sudden rush of involuntary recollection.

Thanks to a combination of this kind of information - the conjunction of people with buildings identified by signs and advertising of various sorts - and historical records such as archives and contemporary newspapers, it has been possible to name many of the people in these pictures.

Most, no doubt, would be completely forgotten had they not taken off their aprons that day, washed their hands and come out to stand for a few minutes in front of their shops. And there are still more who remain unidentified, hard and unkempt faces staring out from under worn hats for an instant before disappearing back into oblivion.

Much of the world Merlin and Bayliss recorded was doomed to disappear. Most of the buildings in what were once bustling main streets have gone without a trace, and in many cases the photographs reveal how flimsily they were built in the first place. Time and again we find a facade is built in neatly sawn timber, but the side walls and roof are made of bark; this is true, strangely enough, even of a baker's shop, not to mention an undertaker, whose sign announces "carpenter, joiner, builder, cabinet maker and undertaker". The logic of tools and equipment leads from one trade to another, as barbers once were surgeons.

The photographs of the goldmines and the miners at work - the activity that supported everything else in town - are fascinating, although the individuals are still likelier to be anonymous. The effort was enormous, but the attraction of wealth was irresistible - particularly the magical lure of gold, the dream of riches conjured from nothing, to be had for the taking, as it were, although in reality the labour was back-breaking. These people for the most part were not professional miners: they were urban proletarians, clerks, even officers or professionals who had thrown in their normal jobs in quest of treasure that would buy them freedom from their hum-drum lives.

This is what makes a picture such as the group of Gulgong miners who pose, standing and sitting, around a mine head so suggestive: one easily imagines this one a schoolmaster a year earlier, that one a shipping clerk and another an officer; and they could be from California or Russia as easily as from England or Wales. Some of them may become rich and end up living in a handsome house, but for the moment they are reduced to the common task, and all are in the same uniform of mud-caked trousers which, as Anthony Trollope wrote when he visited Gulgong in 1871, "have never made and never will make acquaintance with the wash-tub".

There is something fascinating about such images, and perhaps even moving, but not inspiring, for gold hunting is a selfish activity, motivated solely by the desire for gain, and some of these people would have abandoned families to come here. They are not pioneers or nation-builders, although they sometimes played that part unintentionally, as when the massive accumulation of wealth funded the growth of Melbourne and the regional Victorian towns. They were not true settlers, since their jerry-built township vanished so quickly, and they did not open the country for farming or grazing but wrought appalling destruction wherever they went, as we can see in the devastated landscape of ringbarked trees, pits, holes and bogs.

There is no social life in evidence either, and perhaps this is the strangest absence in the photographs, although it is no doubt in part the result of the choice to picture people in front of their houses and shops. We know Holtermann sponsored a brass band, but there is no picture of it playing. There are no shots of amateur dramatics or concerts or any cultural activities; not even of the interior of bars and pubs. There must have been brothels, but there seems no sign of them. Admittedly, this is probably the effect of Victorian prudery, but one can't help wondering whether the lust for gold really had consumed all other appetites.

The most remarkable demonstration of the power of gold over the mind is a poster advertising another of Holtermann's business enterprises: later in life he invested in patent medicines of the snake-oil variety. One of his products was a cough mixture, but the other and clearly the more famous was called simply Life Drops or "life-preserving drops". Whatever these pills contained, there is something so utterly ludicrous about the claim - even in age of bogus tonics - that one has to wonder what could possibly make it seem credible. The answer, it seems, is gold itself, the immortal metal, with its ancient and atavistic associations. The philosopher's stone sought by the alchemists was meant to turn base metals into gold but also to grant eternal life.

And here we find, in place of any argument about the efficacy of the Life Drops, we are offered the simple argument of the biggest gold nugget found. The inventor of Life Drops leans on his nugget, visibly in touch with the source of mystical vitality. But unfortunately neither the drops nor the nugget saved Holtermann, who died at 47.

The Greatest Wonder of the World: The Holtermann Archive, State Library of NSW, Sydney, until May 12.