Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello talks 2025 Australian tour, politics, family life

Ahead of an Australian tour, the Rage Against the Machine guitarist speaks about knocking on Springsteen’s door bearing hellraising ideas, raising a 13-year-old guitar hero in-the-making, and the impossible task of separating his politics from his art.

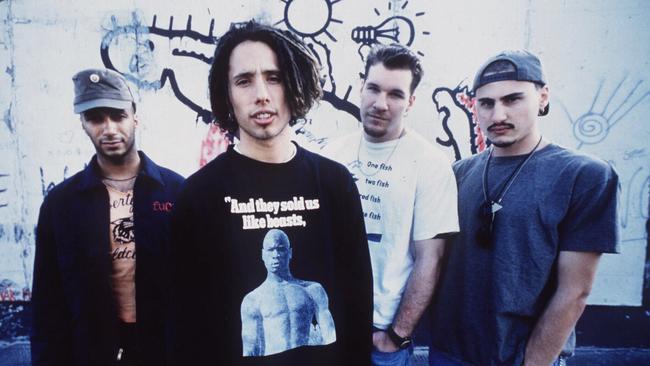

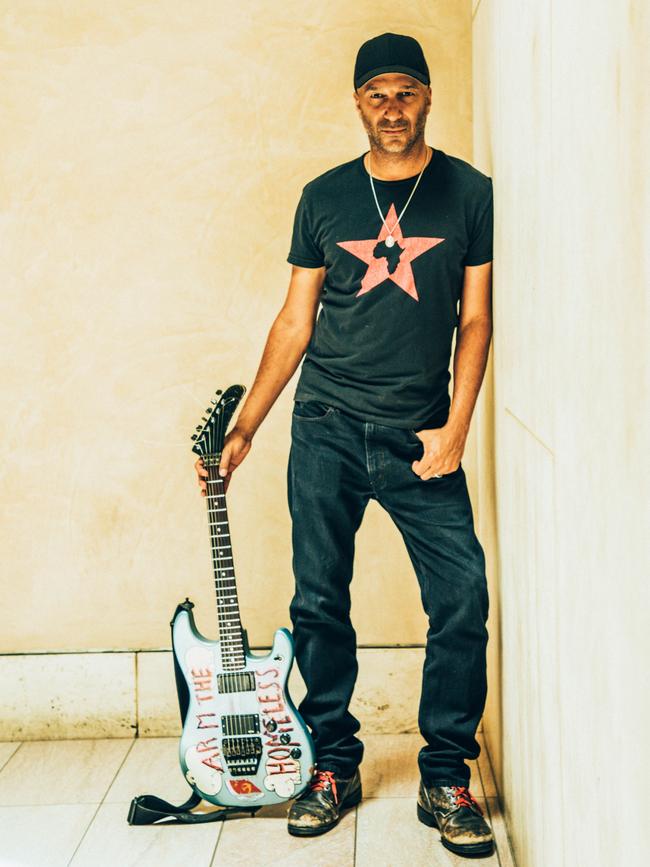

Tom Morello, 60, is an American guitarist and songwriter known for his innovative six-string work with rock bands Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave, as well as his acoustic project The Nightwatchman and a two-year stint touring with Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band.

Ahead of a solo tour, Morello speaks with Review about knocking on Springsteen’s door bearing hellraising ideas, entering the world of musical theatre, raising a 13-year-old guitar hero in-the-making, and the impossible task of separating his politics from his art.

Review: We’re talking ahead of your Australian tour next month, which includes festival shows at Byron Bay Bluesfest. When did you figure out what a Tom Morello concert should look, sound and feel like?

Tom: There have been a number of Tom Morello-oriented shows through the years, but a few years ago I decided to embrace the entirety of my career and my catalogue: Rage Against the Machine, Audioslave, Prophets of Rage, The Nightwatchman, my time with Bruce Springsteen, (2018 solo debut) The Atlas Underground; 21 records, 30-some years are all fodder for the Tom Morello solo tour. While Bruce has the E Street Band and Neil Young has Crazy Horse, my backup band is the Freedom Fighter Orchestra, who I think could go toe-to-toe with any of them. It’s a big-ass rock show that really delivers the goods, and it’s the most fun I’ve probably ever had on tour.

What do you think people expect when they buy a ticket to a Tom Morello show?

Some of my favourite shows ever have been in Australia, from the first Rage Big Day Out festival in 1996 to playing there with Bruce Springsteen (in 2013 and 2014), with Prophets of Rage (in 2018) – and then in (2008) when Rage was headlining the Big Day Out, I would play a Nightwatchman show on the same day, in a tent for 5000 people. This (tour) has been a real labour of love; really connecting generations of fans. On the one hand, (I’m) carrying the torch for Rage Against the Machine and Audioslave – bands that do not currently exist – with music that is very, very near and dear to my heart; music that I’m very proud of, and music that is still a part of the DNA of a lot of music lovers.

How has your relationship with playing live changed across the years?

First of all, for any aspiring musicians out there, there’s no better way to get better than to play in front of an audience, with (proverbial) live bullets flying. I’ve always really felt it’s most alive when connected to an audience – and the good news is that the music that I’ve made has been both so personal and uncompromising through the years, that when it does connect with an audience it’s really a … not to be too overly dramatic, but a spiritual experience, and a celebration of resistance of rock ’n’ roll; of the truth as I see it; of a shared history, which is more important now than ever. I mean, in this day and age, every creative act is an act of resistance. Every truth sung, or true note played, is a beacon of light in the gathering gloom.

The last time I spoke with you was seven years ago, when you visited with Prophets of Rage in 2018. I asked then what your kids thought of your music, and your response was: “I don’t inflict my career on them in any way.” But that’s changed a little in recent years, right?

Sure. My son, Roman, who’s 13 years old, is very talented; while the rest of us were trying to learn how to bake bread and learn French during the pandemic, he was shredding away in his bedroom, becoming quite an accomplished guitar player.

We’ve written some songs together – Soldier in the Army of Love, and the theme song for the latest Venom movie, One Last Dance. I took him on tour; sadly, he will not be in Australia because he’s a student, and he will be in school at that time. I would love to tear him away, but I emphasise education and academics, as well as creating mosh pits: first you’ve got to create the mosh pits in your mind, and then you can later create them on the festival field (smiles).

But my kids never heard Rage Against the Machine; I never played that for them. In 2022, when Rage went on tour (in the US and Canada; later cancelled due to an Achilles tendon rupture suffered by vocalist Zack de la Rocha), that was really the first time where they knew what dad did for a living. They’re like, “He’s not just that guy that sleeps late”, you know? (laughs) It was nice to be able to share that experience with them. And my 15-year-old (Rhoads) is the assistant lighting director when we go out on tour, when he’s available to be there too. It’s a family affair, and really a lot of fun.

What does it mean to you for both of your sons to have joined the family business – part-time, as it were?

It’s really wonderful. For someone who’s been on tour for 30 years, I’ve always made the most of the places I’ve been: I’m up early, out at the museum, or surfing, or meeting wombats in the outback, or whatever. And to be able to do that now with them – and to see the world again, fresh through their eyes – has been really, really great. I let them know: we’re going to play a festival in Madrid in front of 60,000 people, but we have to go to three museums on the day off. That’s the trade-off. (laughs)

What do you see when you look across at Roman sharing the stage with you?

The crazy part about it is I’m now kind of used to it. At first, it was a thrill; he’s a little kid! He’s 13 years old, and he has a kind of moxie that I didn’t get ’til I was in my late 20s. But now he’s just another guy in the band who I can count on, and that’s the part that is pretty trippy (laughs). He joined me last summer in Europe for a solo festival run that I was doing; he was going to play a couple of songs in the set, and I called up to make sure he’d been practising to get them under his belt. He’s like, “Yeah, I got the songs down a long time ago – I’m practising my stage moves.” And sure enough, he unveiled them! (laughs)

Your own method of learning guitar was unique, obsessive and relatively late; you didn’t get serious about playing until you were 17. What was Roman’s approach to learning to play?

It was during pandemic times; there were a lot of guitars around the house, and the kids had no interest in (them) whatsoever. I knew that he was a fan of some classic rock, and he liked Led Zeppelin – so one day during lockdown, I said, “Can you take five minutes away from playing Fortnite, and I’ll teach you the first three notes of Stairway to Heaven?” He said, “I’ll give you four minutes.” So I taught him the first three notes, and the next day I said, “Hey, give me another four minutes, let’s learn the next thing.” So he was six notes in – and on the third day he asked me if he could learn the next notes.

That was really building those early successes; not biting off more than we could chew, not starting with something boring like scales, or even tuning the guitar. It was just like, “Here’s a song you like – let’s play that song.” It’s not the easiest song in the world, but we played it in its entirety – and then he wanted to learn the solo to that. I just thought, “Let’s run before we walk,” and long before he knew the names of any chords, I taught him improvisational soloing. So I’m now the rhythm guitar player in the household; I just play some chord progressions, and he shreds over it, and that’s how he got it started.

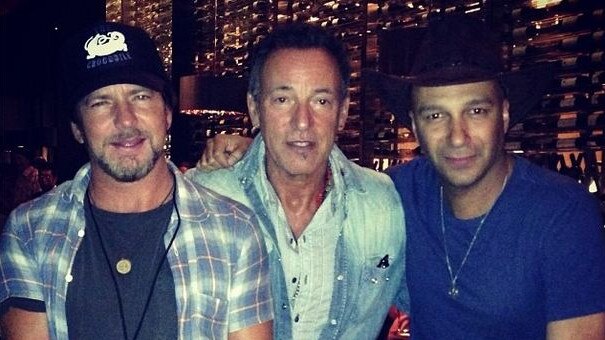

In terms of calling in favours from friends, where does your 2021 cover of AC/DC’s Highway to Hell – featuring both Bruce Springsteen and Eddie Vedder – rank?

(laughs) We first played that in Melbourne, at Bruce’s stadium show there (on February 15, 2014 at AAMI Park); Eddie just happened to be in town on a solo tour, and was at the show. We had been rehearsing Highway to Hell, and I was never scared to knock on Bruce’s door with an idea. Some of them he liked; some of them he didn’t like. This one he liked. I said, “What if we open the show with Highway to Hell, with Eddie Vedder singing – in Australian?” Bruce was like, “That sounds like a pretty good idea.”

I mean, it was really an apex moment of our rock ’n’ roll lives; people were just losing their minds. During pandemic times, again – when we were all separated by thousands of miles – I called those guys up and was like, “You remember that awesome time when people got together and really lost their minds playing rock ’n’ roll?” And they were like, “Yeah, man, let’s record that song!” (laughs) It wasn’t so much calling in favours as sending up the Bat-Signal.

You recently announced a stage musical at the Goodman theatre in Chicago called Revolution(s), which will debut later this year. Are there any comparisons to be made between the worlds of musicals and rock ’n’ roll?

Oh, there’s some enormous surprises. First of all, people do what you ask them to do! That has not happened once in rock ’n’ roll, in my career (laughs). I remember being at rehearsal, and you’d make the smallest suggestion, and people will try anything; they’re eager. Every time I see my collaborators on this, I always comment on that: “Wow, man, in rock ’n’ roll, you’re lucky if you can get four dudes to a stage at any point.” One of the things that it does have in common, though, is the immediacy of performance. When we did the workshop, when a song or a dramatic moment lands right, like in the concert setting, it’s something that you could feel really deep in your soul.

In announcing it on Instagram, you wrote, “Every act of art right now is an act of resistance. Every truth spoken is a beacon of light in the gathering darkness, and every song sung is a trumpet of hope to the future heroes who will undo this madness.” How much are those ideas on your mind at the moment?

(laughs) In some ways, that’s all that’s on my mind. We’re at a particularly challenging juncture in human history, where the palette of impending disasters is broad – but it’s not the first time where humanity has been faced with a seemingly insurmountable crisis, and it likely will not be the last. The way that I look at it is, to whatever capacity – as an artist, as a guitar player, as a songwriter, as someone who’s involved in both putting together international rock shows and musical theatre in Chicago, to writing a batch of songs for my next record, which will hopefully be out this year … at different times in my career, you have the torque, the power, the ability as that beacon; it’s like the force of a fleet of aircraft carriers. At other times, you have a Molotov thrown from behind a burnt-out car in a dark alley. But regardless of which of those sonic weapons is in my hands, I’m going to do it to the best of my ability. I’ve never been able to think any other way than: confronting injustice is what I need to do with my God-given gifts.

I spoke with Bob Geldof recently, and he lamented that “rock ’n’ roll as an instrument of change is over”. How does that comment strike you?

Well, he hasn’t been at one of my shows lately. That’s how that comment strikes me. On the one hand, the part of what he says that rings true is that there’s not a Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young singing Ohio that’s on every radio station (as it was in 1970). There’s not a Rage Against the Machine making five videos for an album (where) people are forced to think about the Zapatistas, or the writings of Noam Chomsky, or whatever. But there is a lot of music that may not be at the top of the charts that is written for these times.

You became musically active with Rage under Republican presidents – namely George HW Bush with the band’s self-titled 1992 debut album – and you’re living and working under another one right now. How much does the political climate affect the art you’re making and performing?

Let’s say that good political art is always created on enemy territory. It should be oppositional; it should be confrontational. It should – if done right – move the goalpost and make people consider not just other ideas, but other sounds than the ones that are being force-fed them by the mainstream. That’s what the best rock ’n’ roll – the best punk rock, the best hip-hop, the best folk music, the best EDM – has always done.

When I last saw you perform here in 2018 with Prophets of Rage, at one point you flipped over one of your guitars to reveal a blunt message written on the back: “F..k Trump”. Is that instrument still in your live arsenal?

(laughs) Well, that billboard space is for rent, depending on what ideas I currently have, or what city I’m in. But the ‘F..k Trump’ thing never really goes away, does it?

A common reaction to outspoken artists such as yourself is to stay quiet and stick to making art. What’s your response to that sort of attitude?

(laughs) Well, from the very beginnings of Rage Against the Machine, I think that we outflanked that; you can’t differentiate the point of view from the music. But people only say that when they disagree with your point of view; that’s the only time that (comment) ever comes up. Certainly in our country, the idea that somehow you’re required to relinquish your First Amendment freedom of speech rights when you pick up a guitar is so ridiculous. I would say that you’re doing a great disservice if, in whatever your vocation, you leave what you think and believe behind – whether you’re an interviewer, or a carpenter, or a student, or a plumber.

Art should reflect the human condition. And so there should be songs about love and about enjoying fast cars; those are parts of the human condition. So too is revolution. So too is standing up against injustice and oppression. Why should that particular segment be left out, because it offends people who disagree with that point of view? They can always turn the channel.

When Rage was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2023, you spoke directly to the band’s many fans: “If you’re bummed out you didn’t get to see Rage Against the Machine, then form your own band and let’s hear what you have to say.” That’s an electrifying, inspirational call to action.

Well, that’s the whole idea. People complain, “The world’s going crazy – where’s Rage Against the Machine?” I’m like, “Well, where’s your band? Where’s your painting? Where’s your play? Where’s the union that you formed at your work? Don’t just sit there on TikTok waiting for it to happen; you’re in it too, man!”

I don’t exempt myself from that: I’m as disappointed as anyone that there’s not a Rage Against the Machine ‘Let’s Destroy Fascism’ tour in the middle of the Trump presidency – but I’m not sitting around crying about it. I’m gonna do a global tour of my own, and continue to make music that has the same zeal and purpose that I’ve always had since I’ve been in bands.

You ended that 2023 induction speech with this quote from your mum, Mary Morello, who’d just turned 100: “History, like music, is not something that happens. It’s something you make,” she said. When you look back at the history you’ve made through your music, what do you feel?

Oh, that’s an interesting one, because I don’t do that; I’m in it right now. There’s a kinship that I have with Bruce Springsteen, when I was on tour with him. We have some commonality of purpose in a lot of different ways, but the one thing that we definitely have in common is: tonight’s show is going to be the best show. And tomorrow’s show? We’re gonna top it.

That’s the way I look at it. It’s not so much reflective. I’m proud of the music that I make. The north star of my making music is one that is carved in stone. I was in a band before Rage Against the Machine (named Lock Up) that made a lot of artistic compromises to try to be successful, and we were summarily dropped (by record label Geffen). I was 26 or 27 at the time, and I made a solemn vow: I’m never going to play another note of music that I didn’t believe in.

I’m just on that journey, you know what I mean? Some of those records have sold four million copies, and some of them have sold 40,000 copies. I’m just as proud of one as I am the other. It’s all part of the same fabric.

Tom Morello’s Australian tour includes shows in Melbourne (April 13), Sydney (April 16) and at Byron Bay Bluesfest (April 17-18).

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout