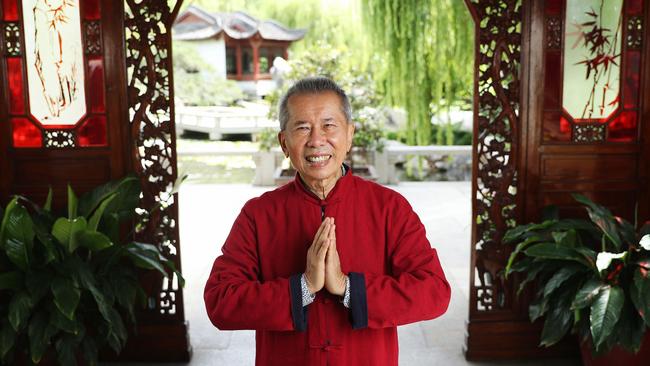

Photographer William Yang, lens of curiosity and compassion

Photographer William Yang takes us into the world of a man who grew up as a member of two minority groups in a place and at a time difficult for both.

People find it hard, if not impossible, to establish a sense of self or identity without comparing themselves to some other group that they hate or despise. The supposed difference, the hated otherness, is often imperceptible to third parties: the rest of the world was bemused by the level of ethnic hatred that broke out between the closely-related peoples of the former Yugoslavia, and we are regularly surprised by tribal butcheries in Africa. We cannot understand the bitter enmity of Sunni and Shia, and have almost forgotten the hostility, in our own world, that once divided Catholic and

Protestant.

But if there is something poisoned about such a sense of self, it is because it is a morbid phenomenon in the first place, which arises out of anxiety, insecurity and competition for resources. We see this even in the most banal of suburban environments: as soon as someone is upset with a neighbour, they will characterise them with some contemptuous reference to their ethnic origin, religious belief, social class, sex or even age.

When we are happy and confident, we don’t think about self or identity, we are simply content to be what we are, although that apparent serenity is partly fortuitous and can also be the result of good fortune, combined with an unexamined existence. Real wisdom, as philosophers and religious teachers have explained, lies in becoming aware of the ego, understanding its role and limitations, and as far as possible transcending its morbid manifestations.

Today, however, we are surrounded by morbid pathologies of the ego in the pervasive obsession with various forms of identity; group identity, in this sense, is simply a collective manifestation of ego, and like all forms of the morbid ego, it arises from insecurity and competition for survival, and inevitably entails the expression of violent hostility towards some other group, conceived as its counterpart and antagonist.

What is the origin of the insecurity that underlies this phenomenon? Many factors have contributed to unsettling the modern mind over the last century and a half, but in the past 40 or 50 years the most important of these factors has been the globalisation of the world economy, which has brought new prosperity to many, but has at the same time impoverished the old working classes in the industrialised world, leaving them vulnerable to populist

exploitation.

But a phenomenon that would once have been seen through a socio-economic lens is now seen through an identitarian one. America, for example, does indeed have inherited and entrenched racial problems, but the most conspicuous crisis is economic: there is an untenable and growing gap between rich and poor, the kind of gap that used to characterise South American banana republics rather than the US with its once affluent working class. Meanwhile our intoxication with innovative and disruptive technologies has only aggravated the state of affairs, because it is not only traditional capital but especially traditional labour that actually gets disrupted.

The idea that so-called “people of colour” are the ones to suffer in this situation is profoundly disingenuous. On the one hand it is not all “people of colour”, since Asian-Americans, because of their understanding of the importance of education, are winners in the new economy. Consequently they are not drawn to aggressive and self-pitying identity narratives. The losers are poor blacks and poor whites. And the result is not only black identity agitation, but also white identity agitation, as we saw last year with eruptions of tribalistic self-assertion on both sides.

This is perhaps the most interesting thing, to realise that white supremacists are essentially a disaffected minority group, exhibiting the same outlook of resentment and self-pity as other militant minorities. And the same is true of far-right and neo-Nazi groups throughout Europe; this is one reason their actual political allegiances and programs can be elusive, since they are more concerned with expressing their rage and alienation than anything else.

It is significant that white supremacists in Europe typically focus their rage on immigrants, whom they see as competing with them and somehow compromising their national identity, as well as on traditional enemies such as the Jews.

But it is also interesting how obsessed they are with homosexuality, as we saw in the recent events in Georgia (complicated by reports of widespread homosexual practices within the Georgian Orthodox Church, which is strenuously opposed to homosexuality).

Such anxieties about sexuality are another example of the displacement of social and economic realities by symbolic and identitarian illusions of the self. In fact white supremacists and neo-Nazis, with their violent assertion of a powerful, virile national self, expressed through hostility to those they imagine to be a threat to their nebulous essence, are among the most instructive examples of identity politics today.

William Yang’s work, surveyed at the Queensland Art Gallery, takes us into the world of a man who grew up as a member of two minority groups in a place and at a time difficult for both, and who has documented the experience with lucidity, sympathy for others, and without identitarian resentment.

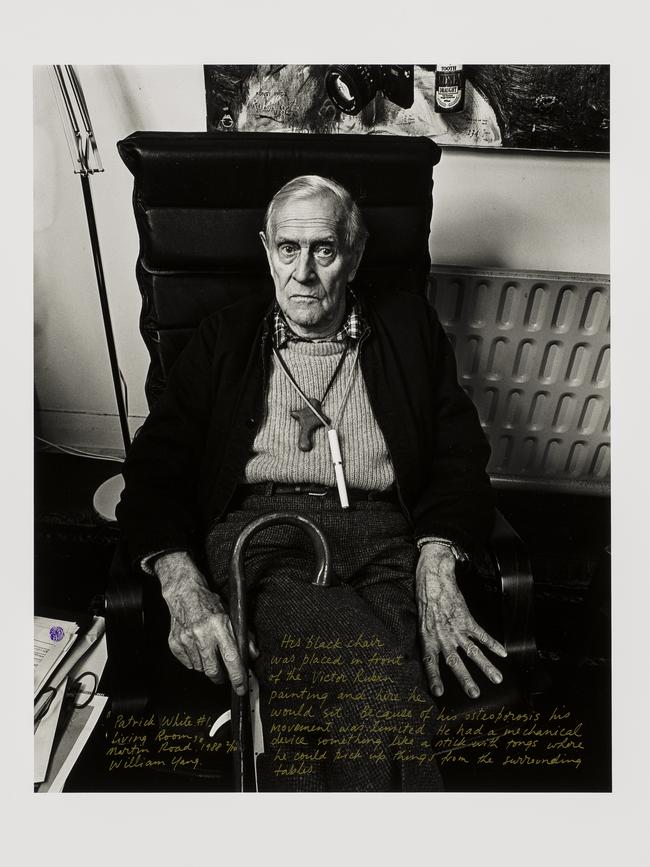

His primary medium is photography, but for many years he has performed on stage as a storyteller of his own life, and his photographs are typically inscribed with narratives related to the images.

Yang is from a Chinese family, but one already well-established in Queensland, so he had none of the experience of a migrant coming to a new land. On the contrary, one of the most telling, as well as touching stories recounted in a series concerned with his childhood is of being completely unaware of being “Chinese” – a testimony to the environment in which he grew up at home – until a little boy at school taunted him with a childish insult. Then he had to ask his mother if it was true that he was Chinese. He recalls her affirmative answer being quite uncompromising, as though this was something that had to be faced.

Another series evokes the ambiguous status of a well-to-do Chinese family, telling the story of his uncle, who owned sugarcane plantations but was murdered in obscure circumstances by a Russian foreman, probably in a quarrel over fraudulent accounts. The story implies that, established as the family was, the law in Queensland may not have been enforced with the same thoroughness and rigour for a Chinese murder victim as for a white man.

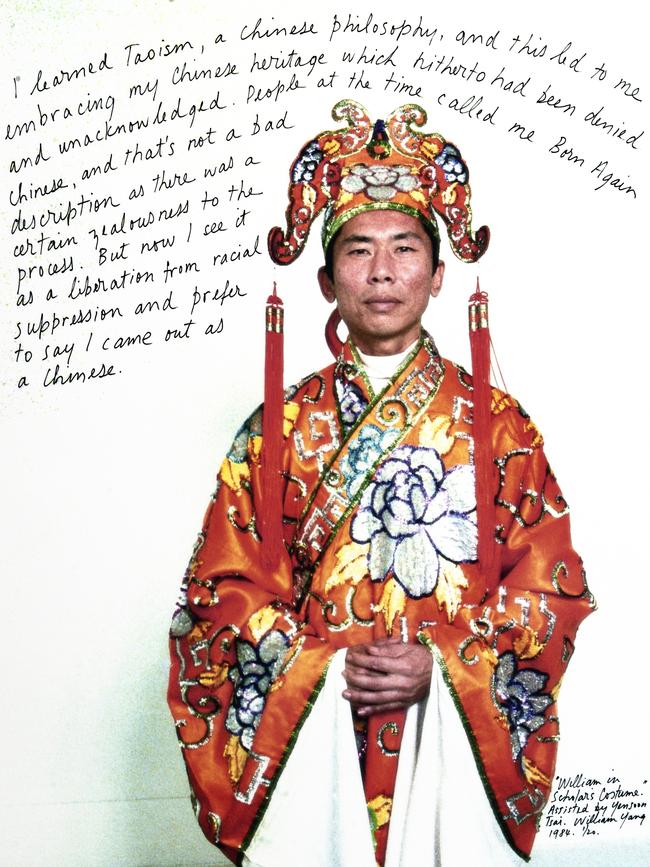

But like Lindy Lee, whose retrospective at the MCA was discussed here last November, William Yang grew up first of all as a young Australian rather than as a self-conscious member of an ethnic minority, and his discovery of his Chinese heritage has been a progressive journey. He reflects on an experience shared by many Australians whose forebears came from non English-speaking countries but who grew up here with English as their native tongue – of visiting the land of one’s ancestors but not knowing their language.

Just as Lee has gradually adopted Buddhism, Yang has been drawn to the even older and native Chinese belief of Taoism, and at some point describes himself as a born-again Chinese. In one striking photograph he portrays himself in the elaborate costume of a mandarin.

Yang’s other minority status, as a homosexual, was more prominent through most of his career as a photographer, particularly in the last quarter of last century. He documented the life of a group that began to demand civil rights and greater visibility during these years, with a series of demonstrations and in particular the Sydney Mardi Gras parade, first held in 1978. Yang was present both as spectator and as participant, and his photographs of these events and of the life of this newly assertive community are among the most vivid documents of the time.

Gay liberation was ultimately part of the broader movement of sexual liberation that had begun in the 1960s and that questioned or opposed most of the norms governing and restricting sexual behaviour that had been nominally at least in force in previous generations, even if in reality all sorts of things had always gone on more or less in secret and more or less tacitly tolerated. Unfortunately, such an arrangement exposed nonconformists of all kinds, from adulterers to homosexuals, to exploitation, blackmail and violence.

The sexual revolution was made possible by two medical advances. The first was the availability of penicillin from World War II onwards, the first really effective cure for venereal disease; and the second was the invention of the contraceptive pill, available from the early 1960s and widely used by the second half of the decade. The threat of syphilis, which had hung over sex for 450 years, the whole of the modern period, was finally lifted, and the risk of falling pregnant, which had always inhibited women, had now disappeared too. The momentum of free love swept up everything in its path.

But sexual activity with another person always carries risks, ranging from physical danger to more intangible and invisible moral costs, and this was not simply a period of unrestrained pleasure.

But compared to the experience of a more recent generation in which everything is available in the dreamworld of digital imagery, it was a time when individuals took genuine moral risks and exposed themselves intimately in engaging with other individuals. There was nothing virtual about their interactions.

So free sex was never really without cost, perhaps especially to women – the benefits were not as equally shared as they appeared to be – and it was never entirely safe. But now there was a still worse threat looming, for by the early 1980s, after two decades or less of liberated promiscuity, the new horror of AIDS appeared, a disease that could not be cured by antibiotics and which caused a wave of deaths as the decade unfolded.

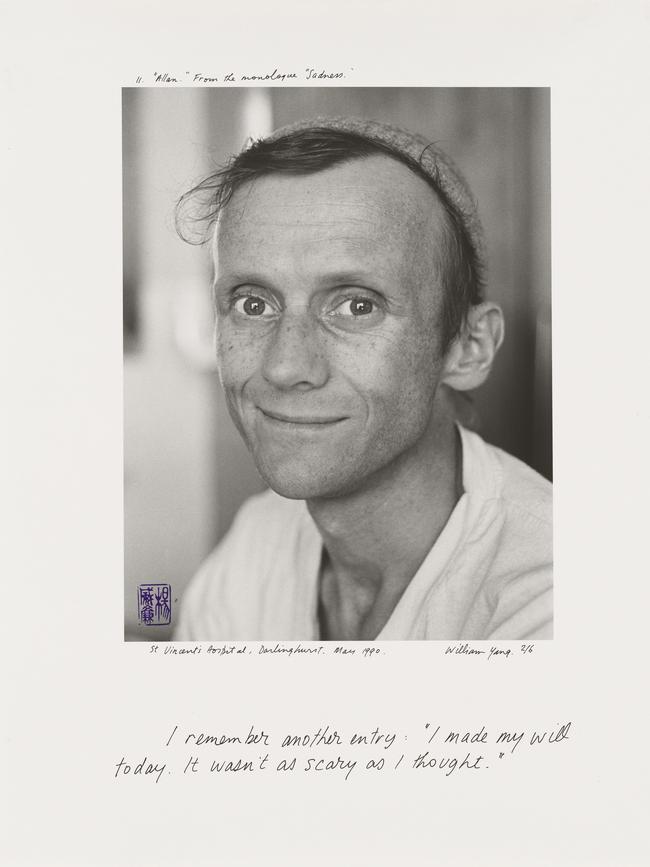

Once again William Yang was on the front line of this crisis and reveals, as no other photographer has, the tragic suffering behind the glamour and theatrical tinsel of the gay nightclubs and drag shows. His most moving series follows the decline of a friend who was dying of AIDS in the early years when the disease was not only incurable but unmanageable.

This series of photographs too is elaborately annotated, so that we follow the story not only in Yang’s pictures but also in his commentary.

The series follows the inevitable process from early days in which his friend is quite lucid and aware of what is happening until the end when he gradually becomes increasingly incapacitated and then slips into a final coma.

It must have been a difficult series to make, but it is an important work which required precisely the combination of qualities that Yang brings to his best photographs: close observation, curiosity and compassion.

William Yang: Seeing and Being Seen

Queensland Art Gallery, until August 22

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout