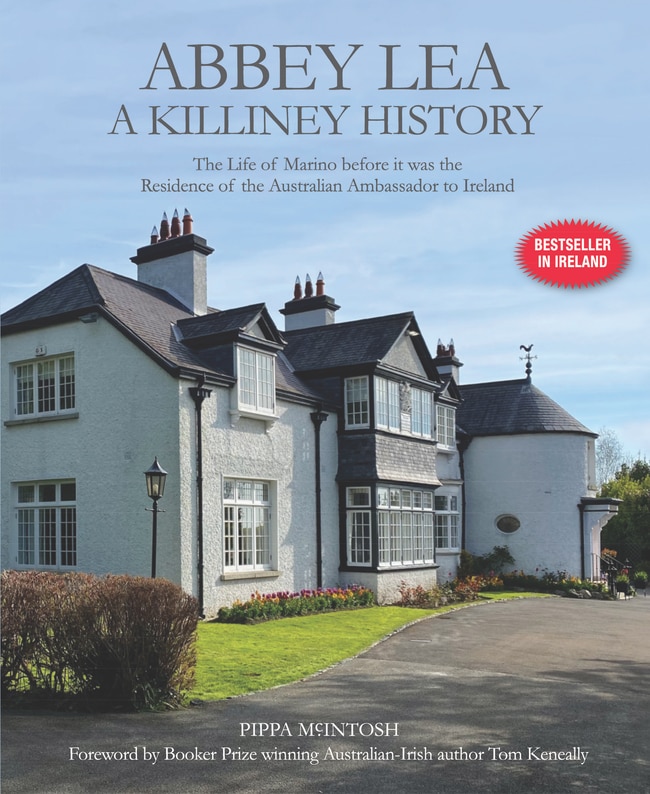

Inside Abbey Lea, Australia’s magnificent home in Ireland

Pippa McIntosh lived in Abbey Lea from 2020 to 2024, while her husband served as ambassador to Ireland. Fascinated by the building, she plunged into the archives and discovered its remarkable history.

That Pippa McIntosh’s history of Abbey Lea – the residence, located on the outskirts of Dublin, of the Australian ambassador to Ireland – has rocketed up Ireland’s bestseller lists is no accident.

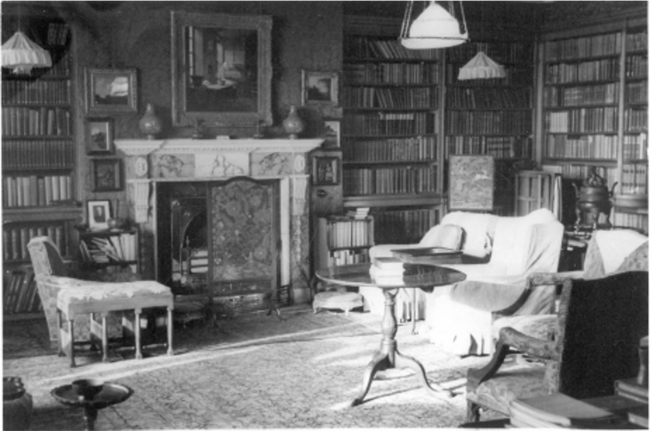

Deeply researched and lavishly illustrated, this book is truly a labour of love. McIntosh lived in Abbey Lea from 2020 to 2024, while her husband, Gary Gray, served as ambassador to Ireland. Fascinated by the building, she plunged into the archives, reconstructing its remarkable history. For Abbey Lea is not only a gem; it is also an outstanding embodiment of the movement that propelled Ireland to the forefront of Europe’s cultural scene in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Abbey Lea’s transformation was the work of Laurence (“Larky”) Waldron (1858-1923), a prominent Dublin stockbroker, civic leader and arts patron. Waldron’s remodelling of the building coincided with the height of the Irish cultural renaissance. By 1894, when William Patrick Ryan published The Irish Literary Revival, the revivalist movement ranged from architecture and literature to music, folklore, and translation. The founding of the Arts and Crafts Society of Ireland that year gave the movement further impetus.

The society shared aims with its English counterpart, which advocated a return to medieval craftsmanship. Hand-working methods, John Ruskin had argued, avoided the alienation inherent in factory labour and ensured creations “honestly” reflected their material qualities. Influenced by Ruskin’s vision, William Morris transformed it into a comprehensive theory that achieved widespread resonance.

There was, however, a key distinction between the Irish arts and craft movement and its English parent. Ruskin and Morris used spiritually charged medieval arts to contrast with Victorian Britain’s materialistic, commercially driven ethos. For the Irish, harking back to the past was not a reaction to modernity; it was primarily a means of reaffirming a pre-conquest era of national glory, countering British stereotypes of an uncivilised, brutishly primitive Ireland.

The revival was, in other words, integral to Irish cultural nationalism, which it sought to promote by forging an idealised portrayal of Ireland’s past. As the poet T.W. Rolleston put it, the work of all young Irish artists had to glow with “national individuality” drawn from “the past art-life of their country”.

Yet revival leaders staunchly opposed mere antiquarianism. While praising Ireland’s ancient epics, William Butler Yeats warned that they would speak to the Ireland of the day only if they were transformed “into dramas full of the living soul of the present”. To a far greater extent than elsewhere, the Irish revival understood tradition as a stimulus, rather than an impediment, to artistic innovation.

The result was a perpetual tension between tradition and modernity. Idealising the past made change difficult, especially when modernisation clashed with monastic Catholic ideals. Nor was that the only contradiction bedevilling the movement.

Thus, one of its key goals was making craftsmanship widely accessible, yet its handmade works were prohibitively expensive. As a result, its primary patrons were drawn from Ireland’s burgeoning bourgeoisie.

By the late 19th century, Ireland had one of Europe’s most commercially advanced agricultural sectors and boasted the world’s fifth-largest industrial city. As the consumer market boomed, the rapid deployment of an extraordinarily dense railway system underpinned a surging stockmarket – and the vast reductions it brought in travel times encouraged the newly wealthy to build or renovate stately homes, which came within easy reach of the main commercial centres.

It was against this backdrop that Waldron transformed Abbey Lea into an arts and crafts showcase. In documenting that transformation, McIntosh focuses on the stained glass of Harry Clarke (1889-1931), who has been rightly described as the “jewel in the crown” of Ireland’s arts and crafts revival.

Waldron was instrumental to Clarke’s career, commissioning major works, helping him secure other commissions and facilitating his access to funding for overseas travel. Without an Irish medieval precedent in stained glass, Clarke’s work was profoundly influenced by the opportunity to study the windows in France’s Gothic cathedrals and England’s country churches.

But while those examples had a lasting impact, Clarke was a great innovator, both in technique and visual imagery. That was apparent from the outset, when his The Consecration of Mel, Bishop of Longford, triumphed at the 1910 exhibition of the Arts and Crafts Society. It was on that basis that he was commissioned in 1915 to produce the stained glass windows adorning the Honan Chapel at University College Cork. Masterpieces of expression, those works propelled Clarke to the pinnacles of his craft.

Yet there is another side to Clarke’s work which is less evident in McIntosh’s book. As is apparent from Eugene Viollet-le-Duc’s reconstruction of Paris’s Notre Dame, the 19th century Gothic revival placed as much weight on the grotesque as on the saintly. In The Stones of Venice (1851-53), Ruskin had lauded the role in medieval art of the grotesque – a style that combines horror with pleasure, the terror of death with rapture and delight. Calling the grotesque “that magnificent condition of fantastic imagination”, Ruskin praised the Gothic’s “spirit of jesting” which found expression in images that are “perpetual, careless, and not infrequently obscene”.

That spirit permeated Clarke’s work; it was, however, accompanied by a modernistic sensitivity to the ambiguities of identity and of the self. Laden with echoes of Gustav Klimt and Egon Schiele, Clarke was unafraid of portraying sensuality; he was also haunted by an ever-present sense of corruption and decay. Including in his works self-portraits as a tormented soul, he, like James Joyce, resisted the constraints of conservative Irish nationalism and its religious piety.

Waldron, whose obituary was written by Joyce, was no traditionalist and he was unsympathetic to the moralising that later characterised the Irish Free State, as were most of the revival’s leading patrons. Largely Anglo-Irish, and fully conversant with contemporary cultural trends, they were far removed from the period’s sectarianism and prudish self-righteousness. They therefore readily accepted the edgy elements of Clarke’s work, just as they had little difficulty with JM Synge’s criticisms of Irish provincialism and Joyce’s dismissal of attempts to recreate a vanished past.

Yet by stoking the flames of nationalism, the cultural revival acted as its own grave-digger. The passions it helped inflame contributed to the island’s division, through the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and the subsequent civil war, into two entities that each reflected the deeply illiberal values of their majority community. Profoundly hostile to the revival’s modernist aspects, those new entities, and particularly the Irish Free State, stifled it as speedily as they could.

Joyce was a prominent and immediate victim. While Ulysses wasn’t officially banned, its distribution was severely restricted. Waldron secured a first edition, but the book couldn’t be commercially distributed in Ireland.

The impact on Clarke was even more dramatic. His later works were suppressed: the magnificent memorial for the Irishmen who died in World War I; the extraordinary stained glass windows the Free State commissioned as a gift to the International Labour Organisation; a stunning illustration of Faust. Judged offensive, they were withheld for decades from the Irish public.

It is therefore unsurprising that Joyce told his friend Arthur Power that “since the ‘Free’ State came in there is less freedom; I do not see much hope for us intellectually”. As for Yeats, by the time of The Tower (1928), all he could sense was “the Coming Emptiness”, with the revival’s legacy shrivelling to “white glimmering fragments”.

All that is, for sure, well beyond the scope of McIntosh’s book. And Abbey Lea, which was acquired by the Menzies government in December 1965, survived, a fitting monument to a movement whose influence on Western culture was immense.

Giving Australia a presence in Ireland that is as diplomatically effective as it is uniquely prestigious, it brilliantly suits its representational function. By meticulously recording that gem’s history, Pippa McIntosh has done her Irish hosts and the Australian people, whose development was so intimately bound up with Ireland, an outstanding service.

Abbey Lea is available exclusively in Australia through Beaufort Street Books in Perth. They are also selling online.