Peter Kingston, Sydney artist: a ferry for his thoughts

The most appealing aspect of Peter Kingston’s work is its openness, going beyond the ego to the living world around him.

It is not often that one attempts to review an exhibition that is not actually on, but this is a time for improvisation, innovation and unprecedented solutions: university and school courses are being taught remotely; even exercise classes are being conducted online, while bankers and stockbrokers working from their homes or beach houses must be wondering why exactly they pay a fortune for offices in CBD tower blocks.

As readers may be aware, the National Gallery of Victoria took the initiative in closing to the public from Monday, March 16, and most of the other public galleries in Melbourne and Victoria followed suit; a week later, the federal government effectively ordered the closing of almost all non-essential public spaces, and in the course of the week beginning Monday, March 23, the Art Gallery of NSW, the Museum of Contemporary Art, the National Gallery of Australia, the Art Gallery of South Australia and other institutions all shut their doors one after the other. Even in the last couple of weeks before the shutdown the crowds were thinning out. I was in Canberra on the weekend of March 7-8 and then in Adelaide on the weekend of March 14-15, when the federal government announced stringent new measures banning large public gatherings and imposing mandatory quarantine on anyone arriving in Australia. The quarantine announcement, which I heard in the airport in Adelaide, meant the end of inbound and outbound tourism in Australia.

When I visited the Adelaide Biennial on Sunday, March 15, I was almost alone apart from another man who was also looking carefully at the show and taking notes. There was something slightly comical about running into a fellow professional again and again in the empty galleries, so conspicuous among the few desultory members of the public, like two detectives, unknown to each other, at the same crime scene.

On the following weekend I managed to visit the Art Gallery of NSW and Cockatoo Island, the day before the Sydney Biennale was closed after being open for only a week. The art gallery was nearly deserted, although this was not entirely surprising considering the dreariness of the displays; there were a few people on the ferry to Cockatoo Island, partly because it was a beautiful day, but the island staff certainly outnumbered the visitors.

It is disappointing of course for all those involved in mounting these elaborate collective exhibitions that they should close almost as soon as opening, but there is less for audiences to regret. Already in Adelaide, before the closures, it was hard not to feel that the real world had overtaken this exhibition and left it behind, adrift in irrelevancy. All the neurotic introspection, the narcissistic self-loathing and the identitarian self-pity that have been the staples of B-grade contemporary art for years seemed more hollow than ever when the world outside the enclosed space of the gallery was gripped by fear of a deadly pandemic.

The Sydney Biennale was somewhat different and less predictable than the Adelaide show. Its focus was on indigenous cultures around the world, and so it lacked the usual large-scale, slick and expensive installations produced by wealthy and semi-corporate contemporary artists.

This should have been a refreshing change but unfortunately, if perhaps inevitably, the displays were often shrill and obvious in their complaints about the fate of indigenous people in the age of economic globalisation. The loud alternated with the inarticulate, and many inherently opaque or meaningless works were accompanied by labels making extravagant claims for imaginary significance.

Ultimately, however, the problem lay in the cultural self-referentiality of most of the work. It reminds us that we have gained a great deal from the scientific revolution, the Enlightenment and modern secular civilisation; we don’t really want to live in tribal cultures, ruled by superstition, rigid social and gender norms and a dread of occult forces. One of the few works on Cockatoo Island that was aesthetically cogent evoked the Voodoo cults of Haiti, dominated by violent phallic sexuality and the menace of brutal death.

The art of Peter Kingston takes us as far as possible from this lurid and incoherent world, yet there is an interesting connection. So much of the work displayed in both of the exhibitions I have mentioned is sterile because of its individual or cultural self-absorption. Both good art and sanity start with looking beyond the self, including the fallacious collective ego-forms of gender, race and culture.

The most appealing aspect of Kingston’s work is its openness, beyond the ego, to the living world around him, but achieving this has been his artistic journey, which is the subject of the book Peter Kingston: Paintings and Drawings by Barry Pearce, and the exhibition. Kingston was born in 1943 and he outlines the main stages of his own life in an engaging chapter titled My Portrait in Charcoal, Seawater and Moonlight. Among other things he recalls growing up in Sydney’s Watsons Bay, visiting Luna Park — opposite which he now lives — and school at Cranbrook, where his happiest memory was of long afternoon art classes with Justin O’Brien.

His fellow pupil at Cranbrook in the late 1950s was Martin Sharp, a year older and O’Brien’s most talented disciple. They later became friends, but Kingston felt overshadowed by Sharp, as he did later by Brett Whiteley, whom he met in 1970. In the meantime he became friends with Richard Neville, and thus contributed to the student newspaper Tharunka and later to Oz; when Neville came back from London and started the Yellow House at 59 Macleay Street in Sydney’s Potts Point, Kingston became involved with this project too, although he was never a resident.

Cartooning, pop, cinema and naive art all influenced Kingston in his early work, through the figures of Sharp and Neville, but the most important influence of all was Whiteley. He writes of watching Whiteley draw with an extraordinary combination of intensity and tenacity, and aptly describes him as “full of energy, quick, like mercury”. In contrast he quotes something that Neville wrote more recently, comparing him to contemporaries such as Sharp and Garry Shead: “… but Peter was strictly slow combustion … To me he seemed the least promising and the most plodding of the lot, proving yet again the truth of Aesop’s fable about the hare and the tortoise …”

For some years Kingston was interested in pop and comic-book figures, in the manner of Sharp, and then he moved increasingly towards drawing and painting. In these media he was initially inspired by Whiteley’s manner, but the real interest of this book is in showing how he progressively broke free of that influence to find his own authentic expression as an artist.

For although Whiteley undoubtedly had a prodigious talent and could sometimes draw with an extraordinary feeling for the character of the subject, he also suffered from an all-devouring artistic ego and a narcissistic infatuation that could lead to self-indulgence and mannerism even to the point of the grotesque.

RELATED: NGA’s Know My Name | Art galleries go online

Kingston has an entirely different artistic temperament and character. He is not as intense as Whiteley, but neither is he so self-absorbed. His work speaks of his patience in looking at his environment and of a kind of generosity and selflessness in the way he extends himself towards the world instead of dragging it back into his own domain.

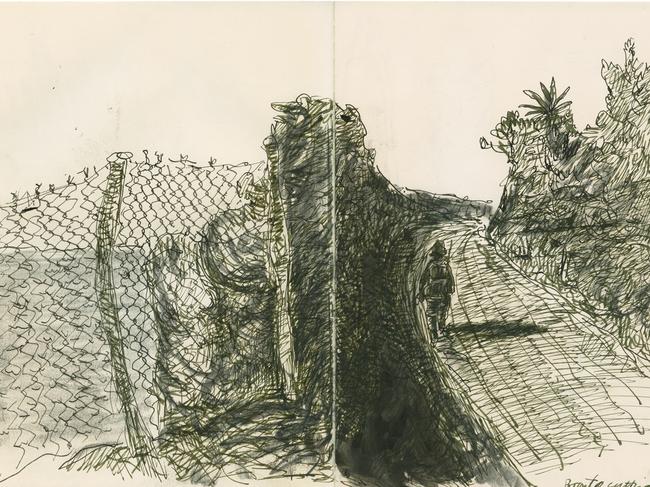

As a draughtsman his line is quick and energetic, full of curiosity, willing to take the trouble to articulate the complex weaving of a cyclone-wire fence, and even drawn towards motifs that are inherently dense and entangled, like a clump of trees, the paraphernalia of a garden or the architectural forms of old timber wharves, harbourside warehouses and domestic dwellings.

The affinity of his views out of windows and down to the harbour with those of Whiteley is clear, yet here too his line has more patience and more curiosity. There is something inherently narrative about Kingston’s drawing: the line tells a story, conveys the character of a place, invites us to follow it in a process of exploration and discovery.

And this is why the art of drawing has remained as interesting as ever, 1½ centuries after the invention of the camera, for the camera is inherently passive and mechanical, even if good photographers can of course make us see things through the many choices of viewpoint and timing available to them. But every element in a drawing is the product of attention, understanding and translation into a coherent graphic language.

Kingston has the natural artist’s talent for seeing the potential for a composition where others see nothing in particular, and also the compulsion to understand things pictorially, to give an account of what things are and how they are made. For visual experience is never exhausted by the pictures we make of it, any more than moral experience by the stories we tell and the poems we compose.

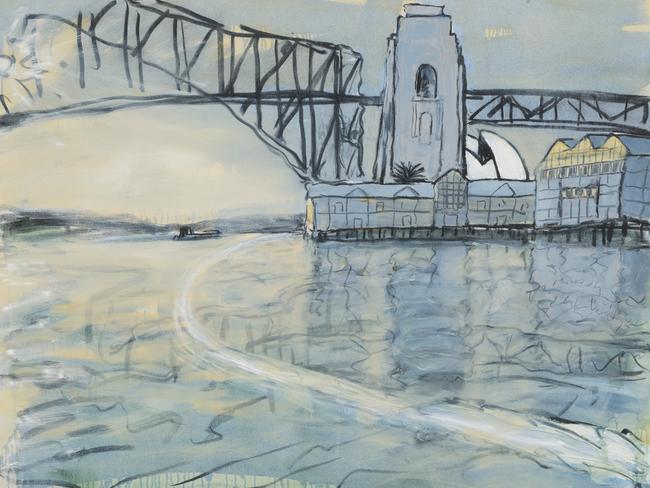

Certain motifs, however, have a special meaning in Kingston’s art. The harbour, with its wharves and boathouses and other shoreline constructions, is ubiquitous. But within the harbour one motif has a special importance: ferries, especially the smaller wooden ones, are transformed in his drawings and paintings into enchanted vessels carrying their passengers, presumably, from one imaginative world to another.

But the more we look at these pictures, the more we realise that it is neither the origin nor the destination of the journey that really matters to the artist. It is the fact that this journey happens over water. Time and again, water occupies most of the composition, and the charm and pathos of the ferries is evoked by their very smallness as they cross the harbour, leaving a long wake behind them.

In the paintings, these crossings are often at night, so that the water of the harbour is dark and the illuminated ferries leave white or coloured wakes behind them and light from their windows reflected on the swell. Sometimes these night ferries are uncannily empty, as in Passing Ferries (1999). Compared with Whiteley’s work, these pictures represent a wholly different level of interest in the harbour, in the sea and in seawater itself. For if Whiteley’s element was fire, with all its potential for self-destruction, Kingston’s is water: fluid, amorphous and mobile.

Sometimes his real subject is the disturbance in the water as a ferry arrives or prepares to leave. In drawing for Wet Day at the Zoo (2016), for example, most of the picture is taken up by the eddies from a ferry that has just docked at a wharf. Here and elsewhere, beyond the endless and sometimes anecdotal curiosity, we feel the suggestion of a deeper metaphysical insight about the nature of the world as an amorphous continuum of being across which we journey and in which our passage leaves mysterious but temporary traces.

First Light: the Art of Peter Kingston

SH Ervin Gallery (dates to be advised)

Peter Kingston: paintings and drawings

By Barry Pearce, Beagle Press

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout