Women put in the frame in NGA’s Know My Name

If you don’t think gender equity in the art world is a problem, then quickly — off the top of your head — name five Australian women artists. Right now.

Sally Smart knows. She’s been there. If you have only a passing familiarity with the art world you might not know her name but Smart is a contemporary artist of the first rank. Her Exquisite Pirate collage, where canvas and fabric pirate ships with jewelled female pirates sailed along white-walled galleries, exhibited from New York to Shanghai. She is a vice-chancellor’s professorial fellow at the University of Melbourne and is the only female artist, actually the only artist, to have been a trustee of the National Gallery of Victoria and a board member of the National Gallery of Australia.

For those who don’t know her name, that’s precisely the point. A great historical imbalance in the art world, the invisibility of female artists, is about to change massively and the change will be impossible for anyone to ignore.

If you don’t think this is a problem, then quickly, off the top of your head, name five Australian women artists. Right now.

Time’s up.

It’s 8am on a Thursday in Melbourne when Smart opens the door of her converted brick garage seemingly forgotten by developers on a street in the inner north and leads me into a light-filled, fabric-draped studio. Soon to turn 60, Smart is an engaging figure who looks like a contemporary artist from central casting. She wants to overturn what she calls the “whole culture approach to creating inequality around visibility”.

“It’ll be the slim volume that women get, not the large volume. And it’s not that they didn’t do the work,” Smart says. “This is what we’re asking for, and we’re asking for it worldwide. We’ve asked for it in the 70s; we’ve asked for it before; the suffragettes asked for it.”

Smart is championing the Know My Name campaign, a push for artistic gender parity in a country where only 25 per cent of the works in the Australian Art collection of the National Gallery of Australia are by women. This month things are to change in a major way. Smart is one of 45 female artists who will swap galleries for the great outdoors on Monday as part of a nationwide billboard campaign to reset the reputation of Australia’s female artists and our relationship with them.

Works by the women will be displayed on 1500 billboard sites nationwide, showcasing female artists to an audience of 13 million, thanks to a deal with oOH!media outdoor advertising group.

Yes, there will be familiar names: Margaret Preston, Margaret Olley, Emily Kame Kngwarreye and Grace Cossington Smith. But also Cherine Fahd, Olive Cotton, Ethel Spowers and Nonggirrnga Marawili. The initiative also includes works by Rosemary Laing, Sue Ford, Margaret Worth, Petrina Hicks and Jean Baptiste Apuatimi.

“There are real social and political and cultural issues at play in Australia,” says Nick Mitzevich, director of the National Gallery of Australia, which launched the campaign. “And our job is to make sure that we connect historical art with the present.”

A major NGA exhibition of 150 women artists since 1900 will be complemented by a publication celebrating the work of Australian female artists written, edited and designed by women. There will also be a monumental video projection across the gallery’s facade on the shores of Canberra’s Lake Burley Griffin, and a giant, floating whale hot-air balloon created by Patricia Piccinini.

Oh, and ultimately, nothing less than a structural rebalancing of women artists throughout public collections seeking a fundamental reappraisal of female artists and our relationship with them. The news is not good, according to the Countess Report, an initiative that benchmarks gender equity. Across the board, representation of women artists increased by up to 20 per cent from 2016 to last year. But state galleries’ and museums’ representation of women fell slightly to 33.9 per cent. Know My Name will build on the #5WomenArtists idea, which was born in 2016 at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC.

“Gender is definitely an issue — always has been,” Smart says, adding that conscious bias and unconscious bias are parts of the problem. “And this is not just the men doing it — women do it to each other as well.”

Let’s rewind to last year. It was pitch day at the NGA.

Mitzevich, installed from the Art Gallery of South Australia to take the national gallery to its next phase, had tasked staff to present project proposals to him.

One slide, composed by Deborah Hart, head of Australian Art, and Elspeth Pitt, curator of Australian painting and sculpture, set the director thinking on a policy to change the course of Australian art. The slide was a composite of mainly self-portraits by about 15 Australian female artists.

“It was so compelling, the gaze of these artists who are not household names,” Mitzevich says. The gallery discovered that only 25 per cent of works in its Australian collection were by female artists.

“So that image that Elspeth and Deborah put up just unfolded all of the questions that we wanted answers from. It also sat very comfortably within the agenda that we want to have, which is to lead a progressive approach to art.”

For progressive, Mitzevich means to review, revise and present different counterpoints about art and Australia.

The NGA council has agreed to gender equity when it comes to both the artistic program and the collection. It will take years to achieve. “But I contend in the 21st century there’s enough good art without compromising connoisseurship and compromising excellence,” Mitzevich says.

Not everyone agrees. Sydney Morning Herald art critic John McDonald has attacked the initiative as an “ideological imperative” and that “it’s the role of the institution to make informed choices, not to tot up two columns”.

Mitzevich thinks the either/or argument is “old-fashioned”.

“It’s actually very easy to follow the canon of art. It’s very easy to do textbook art, what you know. What becomes more difficult is when you want to present a mirror of the world and show the audience the dimensions of art-making in our times. That’s much more difficult because you have to be led by primary research.” Tone is important. The project will not downplay male artists, make value judgments or demand political correctness. “All we are doing is elevating the profile and celebrating the contributions,” Mitzevich says. Show without the tell. Life stories will be showcased but not diktat. “All we are going to do is present a broad cross-section of artists you might not have heard about before. You might like some of them.”

Such as Julie Rrap, 70, whose journey from her early self-organised exhibitions in Sydney in the early 1980s to her inclusion in Know My Name encapsulates the changing times.

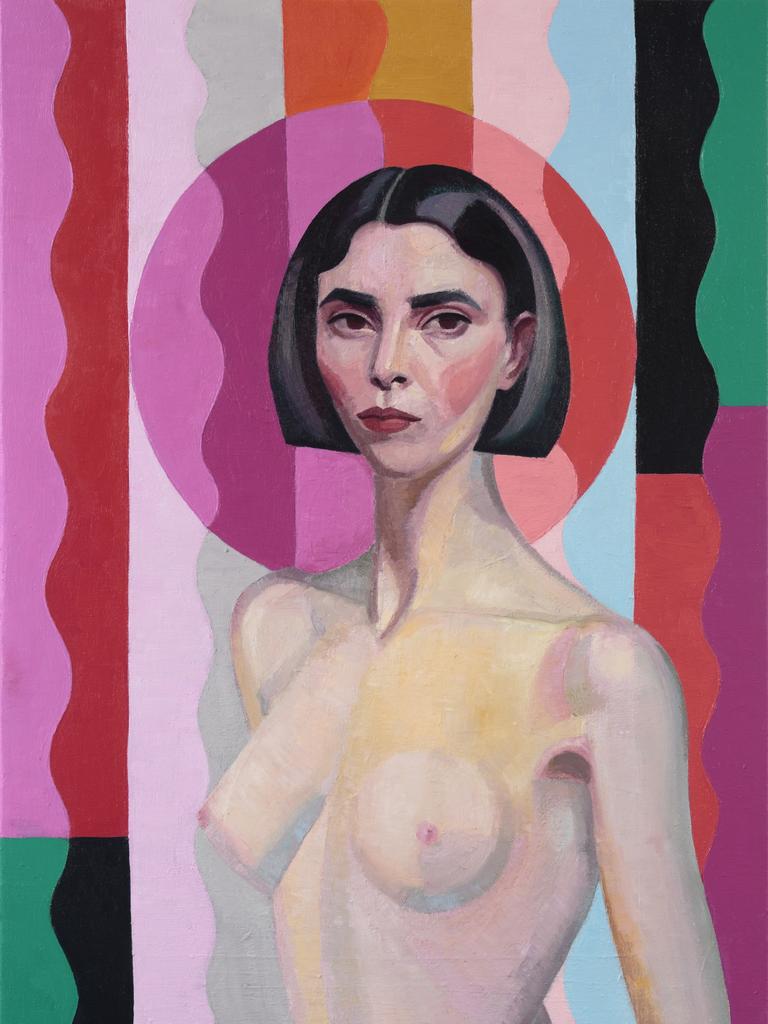

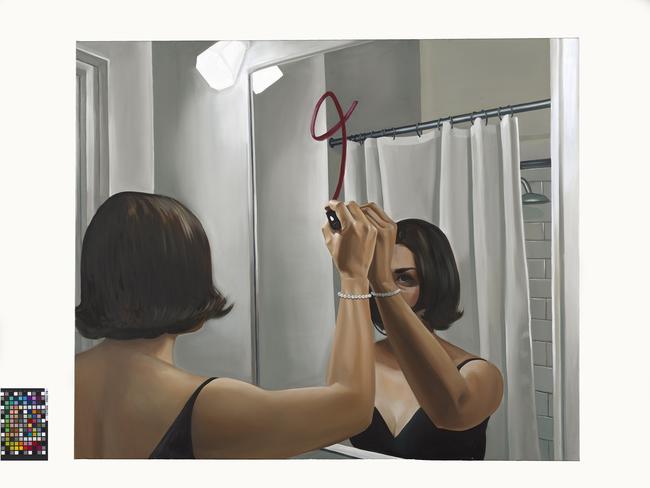

Rrap caused a stir in 1984 with her breakthrough work, Persona & Shadow, bold photos of her naked self, layered atop colourful artworks by Norwegian artist Edvard Munch and printed on life-size shiny luminous cibachrome photographic paper.

The NGA bought two of the pieces, which examine body image and the male gaze, but not the entire nine-part collection. But last year the NGA came a-knocking and, realising the gap in its collection, is purchasing the entire set.

Rrap, an associate professor at the Sydney College of the Arts, says she knows the gallery is buying more historical work from similar artists. “You can play with history but you can’t change it, really,” she says. “The only thing you can do is interact with it.

“The argument is there is still a glass ceiling. There’s a lot of women artists — and I think this is what maybe Nick’s attempting to shine a light on — but how many collections, in a deep sense, are they in? How many survey shows do they have? How many books? It’s a lot better than it was. But if you look more deeply, it’s still not enough.”

Smart recalls the career of another underappreciated female artist from another era. Bessie Davidson was a student of Margaret Preston and made a life and career for herself in Paris, dying in Montparnasse in 1965.

“We don’t have proof but it is said that she did work for the Resistance in the Second World War. The Nazis came to get her and she got out of Paris overnight. She has an incredible story. She’s an incredibly courageous, amazing woman. She had the first Chevalier Legion d’honneur for an Australian woman artist. And she got that before she was 50. And she was a feminist before the word was there.”

Davidson was Smart’s great-aunt. She might, Smart says, have also been Preston’s lover. Certainly Davidson pushed the cause of women artists. “And these are historical and we have plenty of contemporary people who are also unknown, right before you.”

Measured, deliberate, unfailingly polite, Mitzevich is sitting in his modest NGA office, which just happens to be decorated with works by female artists. He clearly wants to galvanise the gallery and the country, and already Know My Name is having a flow-on effect of other galleries taking their cues from the NGA.

“Galleries aren’t as radical as people think they are. We’re as conservative as, you know, the institution up on the hill,” Mitzevich waves in the direction of Parliament House, with its own gender parity problems.

Mitzevich, who tends to refute assertions that run against his grain with studied silence followed by a gentle reframing, says he is not trailblazing, just reflecting what is happening in contemporary society. I put it to him that he’s a change agent. A short pause. “I think that’s a bit grandiose.”

Know My Name is privately funded, in keeping with the view that money follows good ideas. The goal was $2m, and more than half has been raised, despite the abrupt departure late last year of Alison Wright, NGA assistant director, engagement and development, who had started to negotiate partnership deals with oOh!media, Wikimedia and the ABC. “I’m very happy to lose a bit of skin,” Mitzevich said. “It’s actually my job to put ideas out there. And if they fly, they fly. If they don’t, I lose a bit of skin and I just dust myself off.

“But when you want to contribute to the cultural life of a country and community, you have to put ideas out there that people will consider. Some people will think they’re interesting and curious, and want to learn more about them. Some people will think they were just being cynical and politically correct. Other people won’t care.”

After the interview I wander around, and make a pilgrimage upstairs to view Jackson Pollack’s outrageous Blue Poles, a signature modern artwork that Mitzevich’s predecessor, James Mollison, bought for more than $1m, shocking Australia and placing the gallery on the newspaper front pages, including the memorable “Drunks did it!” headline in Sydney’s Daily Mirror.

“What I love about that era was people had an opinion about art and it was talked about,” Mitzevich says. “That era is gone. And I suppose anything we can do to contribute to people having an opinion about art is valuable. We are not just a storehouse.”

Building a cultural asset only has resonance if there is a dialogue with wider Australia, he believes, and already the campaign is flowing to regional galleries, which are putting more women artists on their walls.

And so too, very shortly, will the NGA. The exhibition, which will feature Rrap, opens on May 30, while a two-day conference at the NGA is scheduled for July.

Opposite the NGA gift shop, a little alcove near the toilets sings with a small collection of very bright paintings by female artists, a precursor to the main exhibition. Deborah Hart, head of Australian Art, reads a quote from Margaret Preston: “Colour is an extravagance of the mind. Colour is the emblem of change.”

“If you want to be successful in art, you have to be as dedicated as sport,” says Hart, who created the original slide with Elspeth Pitt. “Twenty years ago we wouldn’t see women’s sport on TV. And now we see it all the time and that’s what we want.”

Hart looks at the swirl of colour before her. “They shouldn’t be recognised just because they are women — that would be silly — but because of their achievements.”

-

25 AUSTRALIAN FEMALE ARTISTS YOU SHOULD KNOW

JOY HESTER

Born: 1920

Birthplace: Elsternwick, Victoria

Died: 1960

Joy Hester was best known for her expressive ink drawings. She played an important role in the development of Australian Modernism.

PATRICIA PICCININI

Born: 1965

Birthplace: Freetown, Sierra Leone

Patricia Piccinini works across a variety of mediums and captures concerns surrounding bioethics. She was awarded a lifetime achievement award by the Melbourne Art Foundation in 2014.

GRACE COSSINGTON SMITH

Born: 1892

Birthplace: Neutral Bay, Sydney

Died: 1984

Grace Cossington Smith was an Australian artist and pioneer of Modernist painting, most famously capturing iconic Sydney landscapes and glimpses into suburbia. She received the OBE in 1973 and the AO in 1983.

INGE KING

Born: 1915

Birthplace: Berlin

Died: 2016

Inge King was an Australian sculptor who was renowned for producing striking public sculptures made out of steel. She became a Member of the Order of Australia in 1984.

YVONNE KOOLMATRIE

Born: 1944

Birthplace: Wudinna, South Australia

Yvonne Koolmatrie is a renowned indigenous weaver who is committed to reviving the traditional fibre weaving techniques in Ngarrindjeri culture. She received the Red Ochre Award in 2016.

EMILY KAME KNGWARREYE

Born: 1910

Birthplace: Utopia, Northern Territory

Died: 1996

Emily Kame Kngwarreye was an indigenous Australian painter. She is widely regarded as one of the most prominent artists of contemporary indigenous art and was inducted into the Victorian Honour Roll of Women in 2001.

TRACEY MOFFATT

Born: 1960

Birthplace: Brisbane

Tracey Moffatt is an indigenous Australian artist who works mainly in photography and film. She was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2016 and represented Australia at the 57th Venice Biennale.

FIONA FOLEY

Born: 1964

Birthplace: Maryborough, Queensland

Fiona Foley is an indigenous artist who works across a diverse range of mediums. Her artworks spotlight issues that affect indigenous Australians. She received a fellowship from the National Art School in 2017.

ROSALIE GASCOIGNE

Born: 1917

Birthplace: Auckland

Died: 1999

Rosalie Gascoigne was an Australian sculptor and assemblage artist. She found beauty in overlooked, discarded objects. She represented Australia at the Venice Biennale in 1982 and was made a Member of the Order of Australia for her services to the arts.

DORRIT BLACK

Born: 1891

Birthplace: Burnside, South Australia

Died: 1951

Dorrit Black was an influential Australian painter and printmaker. She was one of the pioneers of Modernism in Australia and was committed to both practising, promoting and teaching modern art.

BANDUK MARIKA

Born: 1954

Birthplace: Yirrkala, Northern Territory

Banduk Marika is a printmaking artist who was awarded the Red Ochre Award in 2001 for her work in the visual arts. She was also made an Officer of the Order of Australia in 2019.

MARGARET PRESTON

Born: 1875

Birthplace: Port Adelaide

Died: 1963

Margaret Preston was a key figure in the development of modern art in Sydney from the 1920s to the 1950s. She was one of the first non-indigenous artists to use indigenous motifs in her paintings.

DESTINY DEACON

Born: 1957

Birthplace: Maryborough, Queensland

Destiny Deacon is a photographer and filmmaker who has a particular interest in politics and exposing inequities concerning indigenous Australians. Her works have been featured in numerous exhibitions.

JULIE RRAP

Born: 1950

Birthplace: Lismore

Julie Rrap has worked with a diverse range of mediums and is interested in representations of the body. She has won numerous awards and is a senior lecturer at the Sydney College of the Arts.

BONITA ELY

Born: 1946

Birthplace: Mildura, NSW

Bonita Ely came to fame with her work as an environmental artist in the 1970s. Dr Ely is the head of the Sculpture, Performance and Installation Department at the University of New South Wales Art & Design School.

LISA ROET

Born: 1967

Birthplace: Melbourne

Lisa Roet explores the relationship between humans and primates in her bronze sculptures, among other mediums. She won the Australian National Gallery National Sculpture Prize in 2003.

GEMMA SMITH

Born: 1978

Birthplace: Sydney

Gemma Smith experiments with abstraction. Her paintings and sculptures are held in collections including the Art Gallery of New South Wales and the Monash University Museum of Art.

FIONA HALL

Born: 1953

Birthplace: Oatley, NSW

Fiona Hall is one of the country’s most innovative contemporary artists. She experiments across a range of mediums and represented Australia at the 2015 Venice Biennale.

MARGARET OLLEY

Born: 1923

Birthplace: Lismore, NSW

Died: 2011

Margaret Olley was Australia’s most famous painter of still life and interiors. She was awarded the Order of Australia in 1991 and made a Companion of the Order of Australia in 1996.

SIMRYN GILL

Born: 1959

Birthplace: Singapore

Simryn Gill uses everyday materials to make large-scale works. She shines light on controversial social issues and represented Australia at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013.

JUDY DREW

Born: 1951

Birthplace: Victoria

Judy Drew experiments with pastel to create contemporary works. She was inspired by post-Impressionist and Japanese works of art from the late 19th century.

NORA HEYSEN

Born: 1911

Birthplace: Hahndorf, South Australia

Died: December 30, 2003

One of Australia’s most distinguished portrait and still-life painters, Nora Heysen was awarded the Archibald Prize for portraiture in 1938 and was the first Australian woman appointed as an official war artist.

GRACE CROWLEY

Born: 1890

Birthplace: Barraba, NSW

Died: 1979

Grace Crowley played a key role in the development of Modernism and abstract art in Australia. In 1976, she was made a Member of the Order of Australia, for her services to art.

JENNY SAGES

Born: 1933

Birthplace: Shanghai

Jenny Sages worked in commercial art as a freelance writer and illustrator. She is now dedicated to painting portraits. She has been a finalist for the Archibald Prize at least 20 times.

AGNES NOYES GOODSIR

Born: 1864

Birthplace: Portland, Victoria

Died: 1939

Agnes Noyes Goodsir produced a number of still lifes and interiors, but her most famous works were portraits. Her portraits were acclaimed and widely exhibited in Europe, especially in Paris.

OSCAR ALCOCK

Stephen Brook’s travel was assisted by the National Gallery of Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout