Peru’s ancient golden empires inspire wonder

An engrossing exhibition at the Australian Museum transports visitors back to the mystical and majestic ancient empires of South America.

It has endured as one of history’s most compelling acts of honour and, ultimately, betrayal. While we can never definitively know the precise transpiration, what seems certain is that the last Incan emperor Atahualpa was lured to a meeting at Cajamarca in the northern Andean highlands on November 16, 1532, by the invading Spanish conquistadors under the pretence of diplomatic negotiations.

On throwing a breviary into the dirt – replete with its notorious Psalm 67, calling on all lands on Earth to submit to the Christian lord – Atahualpa would be taken prisoner by General Francisco Pizarro, his gold pilfered, his soldiers and subjects massacred. Over the course of the following four decades the Spanish would conquer the entire country now known as Peru and the surrounding lands known today as Ecuador, Bolivia, Argentina and Chile. Those not cajoled by musket fire were finished off by smallpox.

The living were now forced to abandon their god for another – a Christian god as evoked in the menacing requerimiento that demanded the Incas, like the Aztecs and Mayans before them, submit to the Spanish crown and its lord. “If you do not,” the proclamation read, “I certify to you that, with the help of God … we shall make war against you … take your wives and children, and shall make slaves of them.”

By some accounts, Atahualpa and Pizarro would become cordial during the Incan emperor’s months of incarnation. But Atahualpa’s attempts to sue for mercy in promising to fill a large room with gold, silver and precious gemstones would prove futile. His treasures now claimed as the spoils of empire, Atahualpa – the earthy incarnate of the sun god – would endure one final humiliation in being baptised Francisco Atahualpa, in honour of his captor, before his murder on July 26, 1533, by strangulation.

The reign of the once indomitable Incan empire continues to consume historians and adventurers today. And no destination has proved more alluring or mysterious than the ancient cloud citadel of Machu Picchu, which continues to attract about 1.5 million visitors a year with its temples dedicated to the sun and moon, its terraced plantations and its ritualistic Intihuatana stone.

But the Incans, of course, were the ultimate inheritors of thousands of years of culture and custom, constructed upon and informed by a sprawling mosaic of ancient Andean civilisations – amongst them the Chavin, Moche, Chimor, Nazca and Lambayeque. These civilisations collectively form the subject of the Australian Museum’s latest blockbuster exhibition, Machu Picchu and the Golden Empires of Peru, which opens today.

“Ancient Peruvian societies continue to intrigue new generations,” University of Sydney archaeologist and consultant to the exhibition Dr Jacob Bongers offers. His current research has him exploring the enigmatic site known as “the band of holes” in the Pisco Valley in Southern Peru. “Iconic sites such as Machu Picchu, Chan Chan and the Nasca Lines continue to inspire awe for their scale, precision and mysterious purposes,” he says.

“It is unfortunate that many believe these amazing sites were built by extraterrestrial forces,” Dr Bongers continues. “They were not – they were built by very skilled Indigenous communities. The specifics of how and why these sites were constructed may be elusive, but this is precisely what makes Andean archaeology so exciting. It is this mystery that drew me, and many others, into Andean archaeology.”

Mystery, indeed, remains at the very crucible of this enduring intrigue: from the otherworldly geometric polygons of Kuelap to the cryptic and haunting geoglyphs of the Nasca Lines and the polyphonic sunken chambers and Lanzon statue of the Chavin de Huantar. Of these, the Chavin – who reigned from around 900-250BCE – remain one of Peru’s least understood cultures, and one explored in this exhibition: a cult-like society lead by priests who married sacred ritual with science, pioneering alchemistic and metallurgic technologies that would go on to transform the Americas. Suddenly the transcendental became terrestrial. Humans could aspire to be gods.

Like the colonial experience of Australia, generations of traditional knowledge were wholly expunged across the Americas through brutal subjugation or, at best, strategically co-opted by Catholicism. Having left no discernible written language, ancient Peruvian history has been subject to as much speculation as scholarship: most often interpreted through the purview of the coloniser.

Equally analogous with Australia, Peru’s indigenous communities remain marginalised today, enduring perpetual poverty, discrimination and a shortened life expectancy. Indeed, this exhibition opens in the wake of heated political unrest across Peru as world leaders, including Prime Minister Anthony Albanese, descended on Lima for the APEC summit last week. This civil unrest followed violent clashes between protesters and the security forces throughout 2022-23, sparked by rising crime, economic stagnation and a coup attempt against the President.

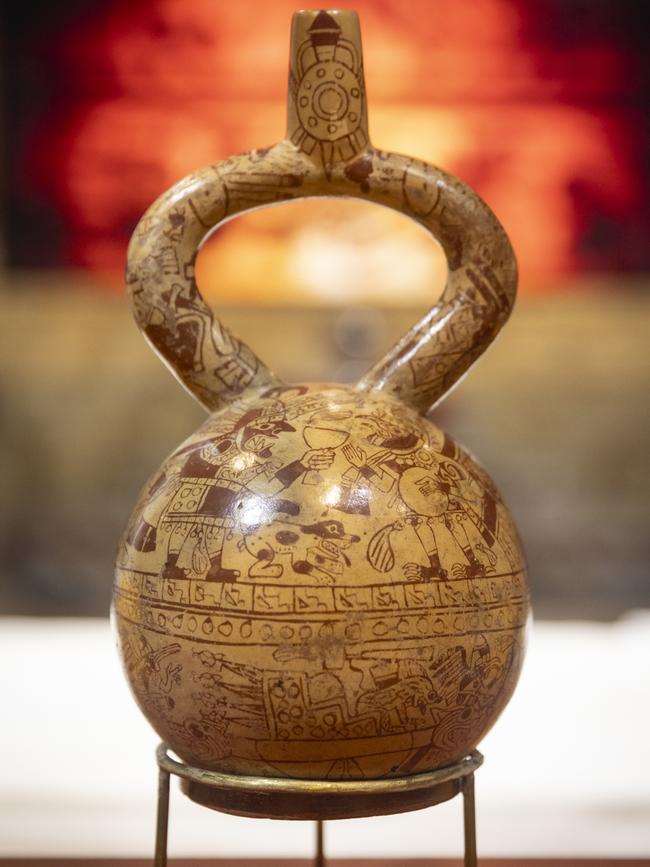

Despite Peru’s complex relationship with its colonial past, it would prove a son of empire – Rafael Larco Hoyle – who in 1926 would establish Lima’s first museum and one wholly dedicated to ancient Peruvian civilisations. The collection has since grown to feature tens of thousands of precious artefacts, including totemic jewellery, gold work, pottery and ceremonial ornaments. It is a curated selection of these that has now made its way to Australia after exhibiting across the US, Italy and France to a collective audience of over half a million.

For longtime environmentalist, entrepreneur and former National Geographic executive Kim McKay, the intoxicating story of these Andean civilisations arrived when she was an impressionable Sydney teenager via a production of Peter Shaffer’s 1964 play, The Royal Hunt of the Sun – a work not without its colonial errancies and bias.

By coincidence, your correspondent shares a similar story – cast as Pizarro’s confidante and second in command Hernando de Soto in a high school production of Shaffer’s play, albeit comprehensively outshone by a prodigious young thespian named Heath Ledger. The late actor’s performance as the play’s shellshocked narrator Martin, a Spanish soldier torn between insouciance and conflicted colonial guilt, has lost none of its prescience in my memory despite the intervening decades. “So fell Peru. We gave her greed, hunger and the Cross: three gifts for the civilised life.”

Taking over as director and CEO of the near two-century-old Australian Museum in 2014 as its first female chief, McKay has overseen a period of seismic transition for the institution throughout her tenure, eagerly embracing technology, virtual reality and courting audiences from outside the traditional museum demographic with blockbuster shows such as Ramses & the Gold of the Pharaohs, which exhibited throughout 2023-24. That exhibition would ultimately tempt well over half a million people through the doors across its six-month run, trouncing attendance records for any exhibition in recent NSW memory.

“Traditional museum practitioners and I might diverge in our approach here,” McKay responds to queries as to the gossamer balance between scholarship and spectacle. “To run a successful and sustainable museum today you can’t rely on the same practices as in the past. You can still be dedicated to storytelling and educating the public, but we operate in a competitive environment – we’re competitive with sporting events, what’s on at the cinema or on your favourite streaming service, and we’re competitive with what’s on the device in the palm of your hand.”

During her years at National Geographic, McKay noticed a discernible spike in magazine sales whenever the subject of ancient Egypt appeared on the cover. The intoxicating cocktail of gold and gods – an appetite the ancient Egyptians and Peruvians share – would prove a perennial boon time and again.

“Maybe there’s something deep in our amygdala where a memory of dinosaurs and ancient civilisations lives on,” McKay exclaims.

“Machu Picchu is right at the top of the public’s bucket-list alongside ancient Egypt, and this exhibition through the artefacts on display, the story that’s revealed and the virtual reality experience will all combine to provide a truly remarkable and memorable exhibition.”

Whilst the show explores these Andean societies’ relationship to agriculture, human sacrifice, mythical heroes, metal artistry, spirituality and even fashion, what may prove inexpungible for visitors is a collection of Moche pots depicting explicit sexual motifs. Many of these works are suspected to be ritualistic drinking vessels, with liquid designed to be imbibed through the figure’s genitalia: a collection otherwise referred to somewhat impishly as ‘50 shades of clay’. But the symbolic potential of these works transcends the purely carnal, and is more likely an exploration of human connection through the unliving, the living and the unlived, and the puissance of cosmic power. At a purely aesthetic and perfunctory level, the craftsmanship is as sublimely staggering as it is often spectral.

“These artefacts are fascinating,” Peru’s former Minister of Culture, now director of the Museo Larco, Ulla Holmquist explains of the pottery. “They represent much more than just human figures or sexual interactions – they reflect Andean cosmology and the connection between nature and humans.

“For example, a pottery piece may depict a male figure with exaggerated features sitting on a stepped throne – symbolic of mountains and leaders in Andean culture. Such representations are sociomorphic: they illustrate natural forces and societal concepts through human forms. Rather than literal depictions, these pieces reflect relationships within nature, such as the flow of water through rivers, seen as a parallel to the flow of life.”

The world’s infatuation with Peru’s ancient civilisations has come at a cost. The environmental impact on places such as Machu Picchu has many, such as Holmquist, concerned as to the physical and historical integrity of the UNESCO listed site. Indeed, whilst citizens of Peru’s former colonial viceroy Spain are – somewhat paradoxically – campaigning to keep unwanted visitors out, the Peruvian government recently raised its conservation caps on visitor numbers.

Holmquist hopes that the Machu Picchu and the Golden Empires of Peru experience will help awaken people’s curiosity as to the diverse range of archaeological sites spread throughout the country, traversing a multifarity of civilisations, as well as illuminate a deeper human connection through time.

“Ancient cultures remind us that humans are part of a larger natural world, not rulers over it,” Holmquist concludes. “This humility toward nature and respect for all life forms is essential today as we grapple with environmental challenges. Embracing this perspective can guide us toward a more balanced and respectful relationship with our environment and each other.”

Machu Picchu and the Golden Empires of Peru opens today and runs until February 23, 2025, at the Australian Museum in Sydney.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout