No bounds: Turnbull unloads on anyone in his controversial and compelling memoir

Malcolm Turnbull’s book is the most provocative and most revealing prime ministerial memoir in Australian history.

In a life spanning journalism, the law, business and politics, Malcolm Turnbull has never been known for half measures or to pull his punches. He says what he thinks and does what he wants, and always has.

He can impress with supreme intellect and cultivate friends and allies with unique charm. But he can also be frightfully determined, utterly egotistical and terrifyingly vengeful.

Turnbull has always struck me as like a 19th century riverboat gambler. There is the brilliant mind and the charismatic personality with style and class in spades. But he can turn.

Before you know it, he has lured you in with his magnetism while robbing you blind. He bets big and usually wins. When you realise it was a mistake to trust him, it is too late. He has a smile from ear to ear.

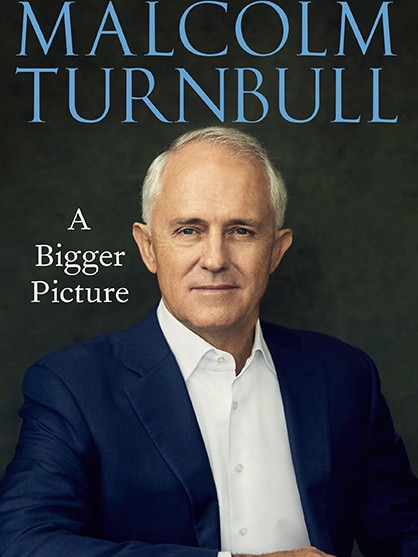

The cover of his full-life memoir, A Bigger Picture, has the author seated at a table in a seemingly relaxed poise. There is no tie ornamenting a crisp white shirt and navy blue suit. But when you look closer, you see a cool, steely determination in his eyes and a wry smile. He could be sitting at a poker table having just cashed in his haul of chips.

There is much to admire in a life that is self-made. Turnbull’s vast fortune was not inherited. He did not advance through various careers by patronage or preferment. It was fired by ambition, hard work and occasional luck.

The central theme of this book is not the bigger picture but rather an untamed and unbound life. He owes little to anyone. He has always been his own man. It should come as no surprise that A Bigger Picture is the most extraordinary, revealing and provocative Australian prime ministerial memoir yet published. There is nothing that compares. Among politicians-turned-authors, only Mark Latham’s wicked diaries (2005), prompt the same gossipy eye-rolling revelation, page after page.

Turnbull frequently jotted down conversations with colleagues. He diarised cabinet discussions. He quotes these along with letters that should be cabinet-in-confidence for at least 20 years. WhatsApp and text messages are harnessed to devastating effect. These give credibility to many of his claims and make for terrific reading. But is it fair, let alone legal, to publish them so soon?

A WhatsApp discussion from 2016 about Tony Abbott wanting to return to cabinet is relayed in the book:

Scott Morrison: It’s more blunt — put me in cabinet or I’ll tear down the govt. There is only one way to respond to that type of approach.

Christopher Pyne: He’s now down to Cate McGregor, Andrew Bolt, Ross Fitzgerald. And he basically writes all three columns by dictation. It’s pathetic, most of his mates have stopped flogging a dead horse.

Mathias Cormann: A reshuffle which leaves him on the backbench would surely remove any hope by formally reaffirming that the party and the government have moved on and that he is not coming back. Backbench or retirement.

Or the private ruminations of Julie Bishop, his strongest supporter, about whether she should challenge Abbott in 2015.

She loathed Abbott and wanted him gone. But she felt she should stand. ‘‘Okay,’’ I’d say. ‘‘I will support you.’’

But then Julie would say, ‘‘If you don’t stand, Morrison could come through the middle and win. And he is almost as bad as Abbott’’.

‘‘Okay,’’ I’d respond, ‘‘you don’t stand and I will.’’

‘‘But then if I don’t stand, I’ll be like Peter Costello and never have a go. But if I do stand, I look like Julia Gillard.’’ And around and around it went.

This is Turnbull at his devilish best; he supports Bishop but parodies her while also revealing her to be a disloyal deputy leader, contemptuous of Morrison, and disparaging of Costello and Gillard. (By the way, Turnbull thinks John Howard stayed too long as prime minister and should have handed over to Costello, even though he thinks Costello was unworthy of the top job.)

Morrison is damaged by this book. He is accused of scheming to see Abbott deposed, wanting Turnbull to replace Joe Hockey as Treasurer, leaking to the media, being a less-than-reliable Treasurer and, in the end, playing a “double game” to seize the prime ministership for himself. Turnbull argues that he too would have won the 2019 election and that Morrison didn’t deserve to win it because of the “coup”.

There are many loaded references to one-time colleagues. If Abbott and Peta Credlin were “lovers” it would be “the most unremarkable” aspect of their friendship, Turnbull writes. A blowout in the cost of renovating The Lodge becomes “the Credlin renovation”.

The book reeks of contempt for Abbott, who is described as bizarre, delusional, dangerous, crazy and toxic to voters. Abbott left the leadership of the Liberal Party starved of funds, unable to pay staff, and without a re-election plan.

In trying to make sense of how he lost the prime ministership, Turnbull takes aim at Peter Dutton and Cormann. He did not realise Dutton’s deceitfulness until it was upon him.

Cormann, the challenger’s numbers man, will never be forgiven. It was a betrayal of the highest order. To succeed as leader second time around, Turnbull thought he had to trust Dutton and Cormann. But it was a Faustian bargain: he traded his soul for power, and they destroyed him anyway.

Even minor players are cleverly skewered in the passing parade of revenge-laden prose. Barnaby Joyce is pilloried, rightly, for lying about his affair with staffer Vikki Campion and their impending baby. In recalling George Christensen’s frequent visits to “seedy” nightclubs in Manila, he mentions that assuming he “wasn’t involved in sex with minors” he just needed to be counselled for “imprudent behaviour”. Ouch.

Conversations in the vice-regal realm are not inviolable either. Turnbull writes that during the chaotic final week of his prime ministership, having survived a leadership challenge from Dutton but as another one loomed, the then governor-general, Peter Cosgrove, “would have welcomed my calling an election” as a last-ditch attempt to cling to power.

Moreover, Turnbull had “no doubt” that if Cosgrove thought Dutton was ineligible to be an MP under section 44 (v) of the Constitution due to an interest in a childcare centre that received government funding, then he would not have commissioned him to be prime minister. That is, even if the Liberal Party elected Dutton its leader and the House of Representatives voted confidence in him, Cosgrove would not have sworn him in. “Any suggestion to the contrary,” Turnbull argues, “is nonsense.”

It is worrying that Cosgrove purportedly held this view. It is irresponsible that Turnbull considered scurrying to an election under vice-regal protection. It would be the governor-general’s duty to swear-in Dutton if he had the support of his party and the parliament. His eligibility to be an MP can only be decided by the High Court.

Indeed, Turnbull writes that he had earlier told Cosgrove: “There was only one institution that could determine an MP’s eligibility to sit, and that was the High Court.” Not the governor-general. But months later, Turnbull, the great republican, was threatening to embroil the governor-general in politics. It would have plunged Australia into its greatest political crisis since November 1975.

Turnbull has no hesitation in being scandalously indiscreet about private discussions if it suits his narrative of being reluctantly conscripted to the prime ministership, soon under siege from “terrorists” within his own party in concert with the sections of the media (including The Australian) but who nevertheless led a towering reformist government until he was brought down by lesser men. Overthrowing Abbott and Brendan Nelson are justified but his overthrow was not.

Blaming the media has become a tedious rationalisation for politicians failing to maintain the support of their party, win elections or deliver reform. It diminishes the intelligence of voters by suggesting a newspaper, radio station or cable news channel determined their vote. Every News Corp newspaper endorsed Turnbull at the 2016 election. And does Bill Shorten think he was given a free ride while Turnbull was prime minister?

In any event, this book challenges much of the accepted history about key players and events in Australian politics over the past 10 to 15 years. It is the first inside account of the Abbott and Turnbull governments. There is just so much to absorb — often presented like a barrister hammering his brief in a captive courtroom — that it is exhausting to read.

Unusually, there is no preface to explain why the book was written or its theme. There is no foreword with a dramatic life-defining moment. It just begins at a galloping pace.

By page 47, Turnbull is already in his late 20s and working for Kerry Packer as general counsel. His swashbuckling adventures as a journalist, lawyer, banker and republican make for fascinating reading as he takes on politicians, the establishment, the monarchy, media moguls and tycoons.

But there is little introspection before being elected to parliament in 2004, at age 50. Turnbull writes about his mother, Coral Lansbury, leaving him and his father, Bruce Turnbull, at age nine. He writes about being bullied in school. But they had no lingering impact.

The book, however, takes a surprising turn when he reveals sinking into depression and contemplating suicide after losing the Liberal leadership in 2009. It is powerful and courageous writing.

READ MORE: Films that help us remember them | Turnbull memoir: A bigger picture: taking shots in black and white

Policy wonks will be satisfied with deep dives into water management, climate change, the NBN, innovation and urban planning. He presents a long list of prime ministerial achievements, and many of these are warranted. His interactions with foreign leaders, especially Donald Trump, are gripping. And there are interesting tales. Malcolm Fraser offered him a job as a media adviser. Bishop asked if he wanted to be ambassador to Washington. The $500,000 Turnbull & Partners invested in OzEmail in 1994 returned nearly $60m in 1998.

Turnbull’s relationship with wife Lucy, which he characterises as a great “love story”, is touching. But if you are looking for an insight into earlier relationships and the urban legend that he strangled an ex-girlfriend’s cat, there’s nothing here. No mention is made of saying Howard “broke the nation’s heart” over the republic. Or what he thought of Warren Entsch signing the spill petition “for Brendan Nelson” which triggered his downfall in 2018.

While the writing is better in some chapters than others it is, overall, an absorbing and compelling read. As a former journalist and author of previous books — The Spycatcher Trial (1988), The Reluctant Republic (1993) and Fighting for the Republic (1999) — he can certainly write. Not all prime ministers have the capacity to speak in fully formed sentences let alone write in polished prose.

Political memoirs are, by definition, an egoists’ genre. They are often dreadful books. Most are written by committee or the subject who has no flair for writing. Not all sell well. Kevin Rudd’s 1326-page two-volume memoir — Not for the Faint-Hearted (2017) and The PM Years (2018) – sold 8200 and 5700 copies, respectively, according to Nielsen BookScan. Gillard found a large audience for My Story (2014) which sold 75,300 copies. Howard’s Lazarus Rising (2010) has been hugely successful, selling 105,000 copies. Bob Hawke’s The Hawke Memoirs (1994) sold about 80,000. Gough Whitlam’s The Truth of the Matter (1979), which focused on the dismissal, sold more than 150,000.

Turnbull has always been polarising. While this memoir is good for history — his elevated ambition for the book — and all prime ministers should be encouraged to write memoirs that provide a window into their lives and their governments, it will win him few plaudits from those who supported him and worked with him.

The risk is that this book cements Turnbull’s reputation as a self-absorbed person who is largely blind to his own failures and motivated by revenge rather than the dazzling, dynamic, can-do man of history wronged by others who looked in the mirror and saw only his brilliant reflection.

Troy Bramston is a senior writer on The Australian and author of the books Robert Menzies: The Art of Politics and Paul Keating: The Big-Picture Leader. He is now writing a biography of Bob Hawke.

A Bigger Picture

By Malcolm Turnbull. Hardie Grant, 704pp, $55 (HB)

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout