David Stratton reviews the Anzac films that help us remember them

Breathtaking battle scenes, stirring stories and the tragic aftermath; David Stratton shares his top film picks to stream this Anzac Day.

On May 1, 1980, I was invited to attend a reception held at the Hilton Hotel in Sydney, at which two of Australia’s best-known businessmen made an important announcement to the invited guests. The men, Rupert Murdoch and Robert Stigwood, were Australians who were well known around the world: the “media magnate and [the] entertainment entrepreneur” (as The Sunday Telegraph reported a few days later) used the occasion to announce the formation of a new company, R&R (later known as Associated R&R Films), a joint venture between News Corporation and the Robert Stigwood Organisation; the latter company had been responsible for hit films such as Tommy, Saturday Night Fever and Grease. A total of $10m would be invested in local productions, the first — and, as it turned out, the last — of which would be Gallipoli, directed by Peter Weir, produced by Patricia Lovell and scripted by David Williamson. When it was released a year later, Gallipoli became an instant classic, and in the years since has been widely accepted as the Australian film about the Anzacs and World War I.

RELATED: The List: David Stratton’s top movies of 2019 | Anzac meaning renewed amid virus: Premier

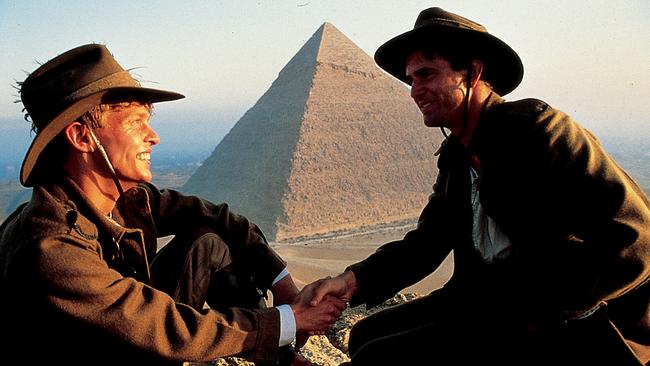

The film focuses on two lads from Western Australia, Frank (Mel Gibson) and Archy (Mark Lee), both runners, who, in 1915, volunteer to serve in the Australian Light Horse, meet and become friends at a base camp in Egypt and then, in the aftermath of the Gallipoli landings, find themselves serving at Lone Pine, pinned down by Turkish forces. These characters are Australian archetypes, played to perfection by the two actors.

The sweep of Weir’s vision, the humour and the tension, the painstaking re-creation of Gallipoli and the cliffs above the beach (scenes that were filmed at a location near Port Lincoln, South Australia) make for a film of astonishing power. The film won nine Australian Film Institute Awards in 1981, including acting awards for Gibson and Bill Hunter (playing Major Barton) and a very well deserved cinematography award for Russell Boyd. The film was a success around the world, and the London premiere was attended by Prince Charles and Princess Diana. It is, despite the tendency to exaggerate the behaviour of “foreigners” (the English as well as the Egyptians) the finest Australian war film.

When the Great War, as it was originally known, was in progress the cinema was silent and Australian films were in their infancy. Between 1915 and 1918 a handful of local films were made, about the war itself (The Hero of the Dardanelles, Deeds that Won Gallipoli, Murphy of Anzac) or about the fear that German spies were infiltrating Australian society (If the Huns Came to Melbourne, Australia’s Peril, The Enemy Within). Copies of these films are no longer available, sadly, so it’s not possible to assess them. The earliest Australian film about World War I that is readily available is Charles Chauvel’s Forty Thousand Horsemen, which was filmed in Sydney in 1940.

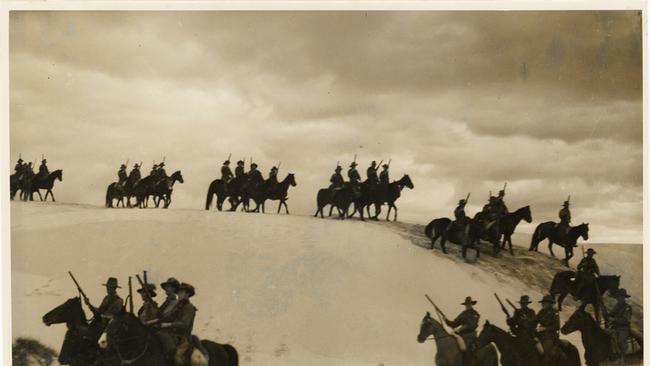

Chauvel was a pioneering filmmaker in this country long before any government support was made available to a film industry struggling in the face of the Hollywood juggernaut. Chauvel and his wife, Elsa, were nothing if not battlers and they succeeded in making five features, two silent, three with sound, before they embarked on their most ambitious production. Chauvel’s uncle, Sir Harry Chauvel, had been in command of the Australian Light Horse during the desert campaign, so there was a personal imperative to bring the stirring story of the cavalry charge at Beersheba to the screen.

The charge itself, a sequence lasting about 4½ minutes, is the film’s climax. It was filmed on the dunes at Cronulla in Sydney’s south, with the co-operation of the Department of Defence, and employed the officers and men of the 1st and 2nd Australian Cavalry divisions. It really is a superb spectacle, beautifully shot by a team of cameramen led by George Heath, and cleverly edited by William Shepherd. The sequence was actually shot two years before the rest of the film and was used to raise money to complete the picture.

All of the battle scenes in Forty Thousand Horsemen are really well staged and filmed, which makes the film’s numerous shortcomings all the more regrettable. These include the casual racism and sexism endemic at the time, the caricatured Germans, the unlikely heroine (Betty Bryant) who poses as an Arab boy and the broad comedy from Jo Valli, who plays a Glaswegian. Grant Taylor and “Chips” Rafferty, on the other hand, are impressive in their roles, though Rafferty’s Jim is made to look a little too insular (he thinks Glasgow is a village in Ireland). He does, however, have this response in answer to the inevitable question “What are we fighting for?” He says, “I suppose it’s about the right to stand up on a soapbox in the Domain; the right to tell the boss what he can do with his job if we don’t like it; and the right to start off as a rouseabout and finish up as prime minister.”

Forty-seven years later the charge of the Light Horse at Beersheba was filmed again for Simon Wincer’s The Lighthorsemen (1987). This time the sequence lasted 14 minutes and is even more breathtaking. Every element of this sequence — the horsemanship, the photography by Dean Semler, the editing by Adrian Carr — is praiseworthy. The scenes that precede it are rather less enthralling; the film, scripted by Ian Jones, begins in rural Australia with the rounding up of horses that will eventually be shipped to the Middle East. Four mates (Jon Blake, John Walton, Tim McKenzie, Gary Sweet) are the comrades at the centre of the drama.

They’re all good but, as was the case with Chauvel’s film, the Australian actors cast as Germans and Turks are far less convincing. In a tragic footnote, Blake, a promising young New Zealand-born actor who had made an impact in the television miniseries Anzacs, was severely injured in a car accident as he drove away from the last day of shooting the film; he suffered permanent brain damage and died in 2011. He might well have had a successful international career on the strength of his performance as Scotty in The Lighthorsemen.

A couple of other films should be added to the short list of local productions that deal, directly or indirectly, with World War I. Break of Day (1976), a delicate drama directed by Ken Hannam, is about a Gallipoli veteran (Andrew McFarlane) recovering from the war in an artists’ community in rural Victoria. And Jeremy Sims’s Beneath Hill 60 (2010) is the story of a Queensland coalminer, Oliver Woodward (Brendan Cowell), who leads a squad of Australians who are digging a tunnel under the German lines on the Belgian front in 1916-17 with the aim of planting explosives beneath the enemy.

The film, scripted by David Roach, is based on real events and characters and the production design by Clayton Jauncey is particularly impressive with the dank, dripping trenches seeming to echo the futility of it all. There’s also a very strong cast including Steve Le Marquand, Gyton Grantley, Anthony Hayes and Chris Haywood. It’s another film that falls into the trap of caricaturing foreigners, but it’s still worth a look this Anzac Day.

Gallipoli streams on Kanopy; Forty Thousand Horsemen and The Lighthorsemen are available on Amazon Prime; Beneath Hill 60 can be found on Google Play, iTunes, YouTube and Microsoft.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout