Naked progression laid bare on canvas: art review

The history of figure painting shows a fascinating transformation of how painters have inculcated nudity through their art.

Last week we discussed the rise of the genre of figure painting based on everyday life, which is confusingly also known as “genre painting”. This category began as minor, informal and even trivial scenes, picturesque and anecdotal rather than strictly narrative. But from the 18th century, and especially during the 19th, there was an attempt to raise it to a new level of moral seriousness.

Scenes of everyday life were now meant to illustrate important social themes, and often to deplore or condemn the personal or social vices of their time. Scenes were replaced with stories, and because painting is not very good at conveying stories that the audience doesn’t already know, compositions had to be filled with hints and clues.

This development was part of a much broader cultural shift that had its roots in the Scientific Revolution of the 17th century, but became increasingly conspicuous with the progress of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. And its causes lay both in a changing religious sensibility and in new audiences for art.

The Reformation had dealt a serious blow to art, and especially to the highest genre of history painting. In England, painting was almost wiped out for a time. In Holland, in spite of an irrepressible love of picture-making, opportunities for ambitious narrative painting were limited, which is one of the reasons that Rembrandt extended the genre of the group portrait so powerfully.

Once again, the concept of genre is central to understanding art: countless pages have been written about The Night Watch (1642), but the fundamental point is that Rembrandt turned a group portrait into a pseudo-history painting. Generic ambivalence is at the heart of every artistic choice in the composition of this picture, as well its dramatic use of colour, light and shade.

The Counter-Reformation gave a powerful impulse to the renewal of history painting, especially for scriptural subjects and the lives of saints: martyrs who had hardly ever been painted before were now enlisted in the Church’s campaign to remind congregations of all who had suffered and died for the true faith. Thus when Nicolas Poussin got his first big break with a commission for an altar piece at Saint Peter’s, the subject was Saint Erasmus being martyred by having his intestines wound out on a winch (1628).

Poussin, who was more interested in using mythological subjects as matter for philosophical speculation, chose not to pursue this line of work. But more generally, the Counter-Reformation support of religious painting was in effect a propaganda campaign, in that respect very different from earlier religious art, from the Middle Ages to the 16th century, almost all of which reflected beliefs shared by artists, their patrons and their audience.

Propaganda begins where shared belief ends: it is essentially the deliberate promotion of beliefs that those promoting them either do not share, or do not share in anything like the same form. And the 17th century is the first period in which dramatic religious images were commissioned for a popular audience by patrons who, in some cases, do not hold anything resembling their religious beliefs.

RELATED: Understanding expressionism | Great art reads you must know

As soon as that split appears between what we believe and what we consider is desirable for the common people to believe, we enter on a path of manipulation. This does not mean that all the religious art now produced is insincere: the best of it is still inspired by spiritual fervour. But the element of manipulation is ultimately corrosive of authenticity and, in the hands of lesser artists, leaves us with little beyond rhetoric and sentimentality.

Religious subjects, then, were undermined by several factors: the hostility of the Reformation, the manipulation of the Counter-Reformation, and ultimately by the waning of faith itself. Meanwhile, the secular subjects drawn from Greek and Roman history, from mythology, from literature, including the enormously popular modern epics of Ariosto and Tasso, all of which reached a brilliant zenith in the first half of the 17th century, began subsequently to run into headwinds of another order.

All of these subjects belonged to a refined literary culture. It was an essentially aristocratic tradition of leisure and learning for its own sake, although it was not confined to the nobility: its practitioners were sometimes penniless men of letters, while even those who had made their money in industry, trade or war knew that real prestige came from the acquisition of this higher culture.

Something begins to change from the later 17th century and, as already noted, this change accelerates through the 18th and into the 19th centuries. A new middle class arises and asserts its utilitarian values; the wealthy still send their sons to fine schools — as they have done ever since — where they are in fact imbued with elements of a classical literary education, but a burgeoning lower-middle-class audience with virtually no higher culture ends up forming the majority of the public that visits such exhibitions as the 19th century Paris Salon.

At the same time, the mythological subjects that were so poetic and mysterious in Poussin’s hands were also put to work by others as instruments of propaganda: Poussin’s contemporary, Pietro da Cortona, was a pioneer in his work at Palazzo Barberini and Palazzo Pamphili in Piazza Navona in Rome.

In the art of Versailles, in the last decades of the century, the gods have been reduced to a kind of bland semi-allegorical retinue for the Sun King.

In the 18th century there were attempts to renew history painting, sometimes with episodes from modern history, as in the examples by Benjamin West mentioned a fortnight ago. Perhaps more importantly, history painting derives renewed vitality from the dynamic political mood of the later 18th century: David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784) is the best-known example, but many other episodes of the early history of Rome are enlisted as exemplars of the new republican spirit.

This political energy carries on, in the aftermath of the Napoleonic period, in the work of certain romantic painters, although they mostly draw on contemporary history, such as Gericault with The Raft of the Medusa (1819), or Delacroix with The Massacre at Chios (1824), or Liberty Leading the People (1830). They also seek inspiration both in contemporary authors such as Byron and the rediscovered author who would be so important for the next two centuries, Dante Alighieri.

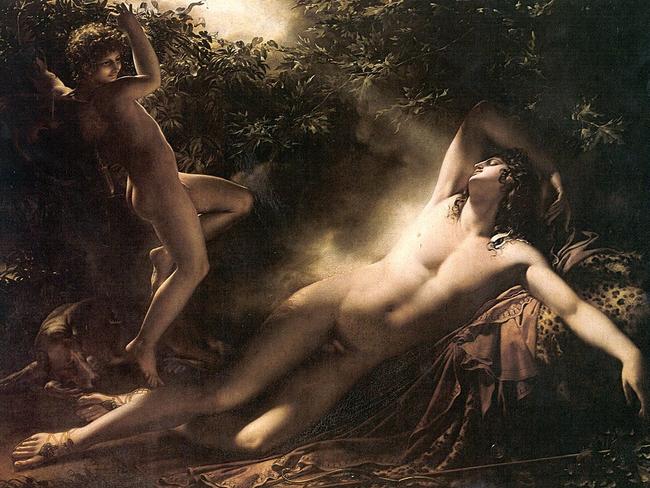

The neoclassical painters who try to carry on the tradition of David and his school, however, and who seek to rediscover the themes of mythology and ancient history often fall into a kind of academic mannerism that verges on camp. There had already been something oddly effeminate in David’s Leonidas at Thermopylae (1814), which Napoleon disliked because of its theme of doom and impending death, and this quality is even more pronounced in Girodet’s The Sleep of Endymion (1791) or Gerard’s Cupid and Psyche (1798).

One could say the same for Ingres’s early Ambassadors of Agamemnon (1801), illustrating the episode in Iliad 9 when Odysseus and other Greek leaders visit Achilles to implore him to rejoin the war. Ingres tried his hand at the modern or mediaeval subjects popular with his romantic contemporaries, but in the end expressed his genius in portraits and in a series of remarkable nudes, of which the greatest is the Baigneuse de Valpincon (1808).

Ingres was not the first to paint the nude for its own sake. Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus (c. 1510) and Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1534) are forerunners, essentially beautiful nudes to which the identity of Venus is ascribed as a courtesy. But these pictures are relatively exceptional and remind us no matter how much the nude was appreciated in earlier centuries for its beauty, it had usually been employed as a figure in a narrative painting.

In such pictures, there is often an exquisite tension between the narrative and expressive role played by the figure and its intrinsic elegance or even erotic appeal. In the 19th century, when history subjects are in decline and the new mass audience for the ever-expanding Salon exhibitions is culturally impoverished, classical titles are too often little more than a pretext or a figleaf for nudes that are at once intrusively naturalistic and cloyingly airbrushed.

Cabanel’s The Birth of Venus (1863) is a perfect example of this kind of thing, and would be familiar to most readers from its reproduction on the label of a mineral water bottle. This painting was exhibited at the Salon in 1863; it pleased the Emperor Napoleon III who bought it for his own collection. Manet’s Olympia, painted in the same year but shown in the Salon of 1865, shocked audiences and critics, not because it was a nude but because it was clearly a prostitute in contemporary Paris.

In this painting, Manet brilliantly took what had become a debased and overused motif, and re-energised it with narrative significance, as a kind of story of everyday life in modern Paris, in which the viewer was awkwardly positioned as the client of a hard-nosed working girl. Here, and in Le Dejeuner sur l’herbe (1853), Manet was interested in uncomfortable truth, but he was not, in today’s fashion, expressing moral outrage or signalling his uprightness: the model in each case was his own working-class mistress.

The modernists who follow in the wake of Ingres, Manet and others are heirs to this question of what to do with the body when there are no stories for it to tell. Degas, one of the greatest, first tries neoclassical solutions, then paints figures of contemporary life, but in his most remarkable figure paintings seeks the body where it is actually at home and even at work in its nudity: in brothels. Toulouse-Lautrec follows him in this direction.

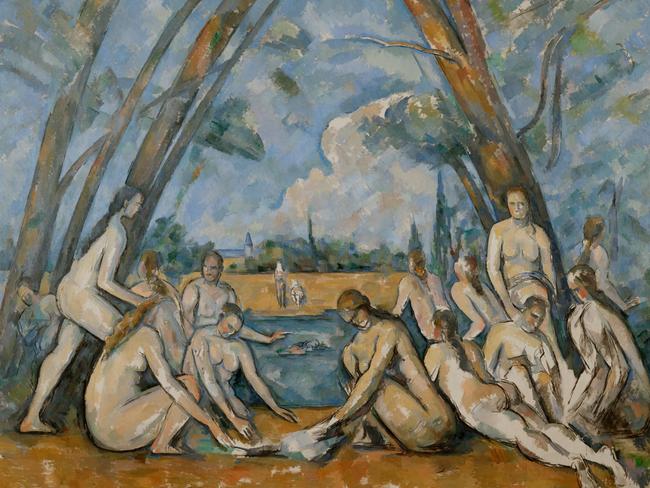

Cezanne’s nudes are especially poignant, partly because he had so little facility with the figure that they are always painfully clumsy, but also because he is so determined to marshal the inherently unemployed and gratuitous category of figures known as “bathers” into monumental compositions.

The figure, as discussed here recently, remains fundamental for both Picasso and Matisse, although Picasso is deeply imbued with the stories of mythology in particular, while Matisse seems happy for his figures to be no more than nudes, with no other purpose and barely any inner life.

The most remarkable painter of the body in the last half-century is Lucian Freud, who took the idleness of the figure to the point of usually painting his subjects lying down and sometimes asleep. Even more flatly than Degas or Cezanne, he reveals the crisis of the figure in the absence of its proper genre — history painting. But it is tempting to see each of them as finding a way out by approaching the body through the perspective of another genre: landscape for Cezanne, animal painting for Degas. While Freud, arguably, sees the body as still life.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout