Dante, Proust and Tolstoy: great literary works you should read

This is the year to have a crack at those literary masterpieces or art monographs we’ve promised ourselves we’d read one day.

One of the most oppressive aspects of crises such as the present pandemic is the way the world shrinks to a narrow range of concerns, constantly repeated and rehearsed thanks to the always-on media of our time. Fixated on their televisions and news feeds, people start to experience the same sort of obsessive and unrelenting patterns of worry and confirmation as those with clinical anxiety.

This mental claustrophobia is of course exacerbated by the physical enclosure that is for many the consequence of social-distancing measures adopted to stem the spread of contagion. It is bad enough at the best of times to be cooped up in a flat or a suburban house but much worse when you can’t have guests and can barely go out.

Humans need space and freedom and movement to feel happy. That’s why it is important to learn ways to move and exercise in a confined space: time to look up some yoga routines on YouTube. But it’s also crucial to make the most of the time that we can go out and walk in the park, unless we are fortunate enough to be able to escape to the country. Simply being able to stretch our eyes out to distant views is an antidote to claustrophobia.

We also need to find mental space, outside the obsessive vortex of coronadata. Meditation helps, but so do routines such as baking your own bread, which I see a lot of friends are taking up now they have time at home: activities that remind you of the most basic things in life and of tasks performed by our forebears for thousands of years help us see beyond our self-centred and temporary preoccupations.

This is also a time for reading.

I’m sure we’ve all set aside on our shelves some big literary masterpiece as something to read one day when we’re convalescing after a vaguely imagined and relatively benign accident or illness. Well, now is the time, and here are a few suggestions.

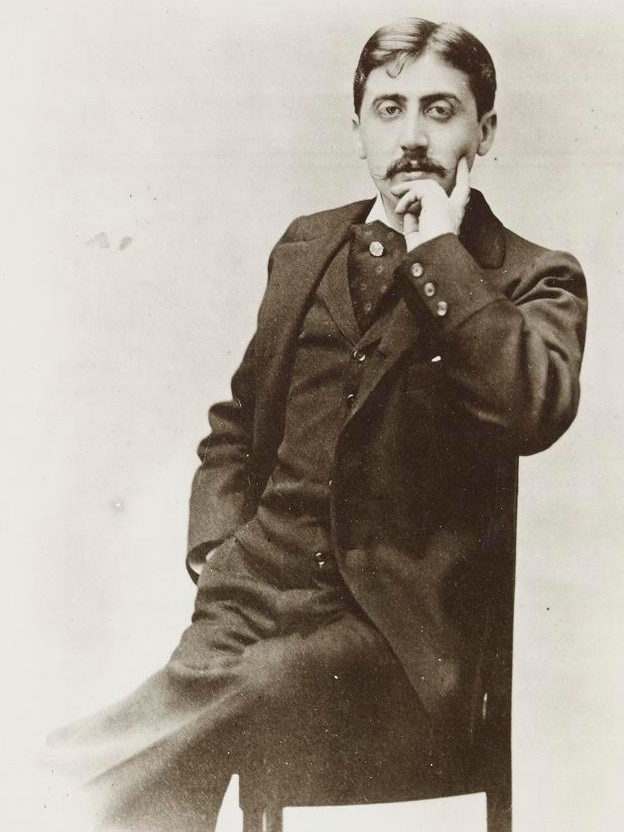

One particular favourite of mine is Marcel Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu (Remembrance of Things Past or In Search of Lost Time), whose first volume was published in 1914, while the seventh and last came out posthumously in 1927. The book begins in a notoriously elusive internal meditation on the verges of sleep and insomnia, evoked in interminably long sentences that have defeated many half-hearted readers. Those who persevere find the novel opens out into an extraordinary narrative with scores of unforgettable and sometimes disturbing characters, biting wit and profound moral insight. On the threshold of final disillusionment, transcendence is glimpsed.

Proust is an author who has inspired a small industry of commentary, biography, even culinary books based on the meals described and art-historical books following the paintings he talks about. Many people have read Alain de Botton’s How Proust Can Change Your Life (1997). But books about Proust always seem to me like excuses for procrastination, for putting off the challenge; this book can be one of the great reading experiences of a lifetime and it will probably take about three months even with long daily sessions.

There are so many others: this could be the year to read Dante’s Divine Comedy, another work many have started and few have finished but that is well worth the effort. Dante is not only one of the greatest authors of the Western canon but also a fundamental inspiration for modern artists and writers from Auguste Rodin to TS Eliot, and what better occasion to read about heaven, hell and purgatory?

RELATED: Of poetry and biochemistry | Novel Nostradamus? Man who predicted COVID-19

Now also could be the time to read Leo Tolstoy’s War and Peace or Anna Karenina, or the novels of Jane Austen, Charles Dickens, Fyodor Dostoevsky, or Honore de Balzac, George Eliot, Henry James or Joseph Conrad; or Stendhal’s masterpiece, Le Rouge et le noir (1830; Scarlet and Black). If you haven’t read James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916) introduces you to his world, before the semi-autobiographical Stephen Dedalus returns in Ulysses (1918-20) in the role of Telemachus. This is a dense book that will take a good month, or longer if you re-read Homer’s Odyssey first, which will make Joyce’s narrative much more intelligible, since he has re-imagined the great epic as the day in the life of a Jewish advertising salesman, Mr Leopold Bloom, in the city of Dublin.

If you are a lover of Joyce, Finnegans Wake (1939) is guaranteed to take you the rest of the lockdown period to read, no matter how long that turns out to be. In fact, with its complex weaving of themes, extraordinary and eclectic erudition and linguistic play drawing on dozens of languages, it is an ideal text to read with a group of friends on some social media platform where everyone can contribute to disentangling the author’s verbal puzzles.

The novel starts — in lower case, because the whole thing is a circle and the final sentence runs on into this first sentence: “riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodious vicus of recirculation back to Howth Castle and Environs”. Readers with an astute ear may be reminded of Samuel Beckett, who was Joyce’s acolyte: his own novels, such as the trilogy Molloy, Malone Dies and The Unnamable, all published in the 1950s and originally written in French, are also particularly suitable reading for a time of confinement.

But now could also be the time to open some of those lavishly illustrated art exhibition catalogues and art-historical monographs that we have all acquired in Australia and on visits to the great museums and galleries of the world, and that too often end up sitting unopened on the shelves of living rooms, reminding us and our guests of our wide travels and implying at least depth and breadth of culture.

At the same time, online access to the collection of great museums has improved enormously in recent years, and since the coronaclosures many institutions have made additional efforts to allow digital visitors to enjoy their permanent collections and their currently closed special exhibitions.

During the next couple of months, then, it could be useful to revisit some of the great artists of the modern and pre-modern centuries, as well as some of their recurrent themes. But we should perhaps start by discussing some broader and more fundamental categories we sometimes take for granted in discussing art. The first of these is the concept of genre, which really just means kind. Most people, even those who have never heard the word, understand genre in the case of films. Within moments of the curtain opening, from the combination of locations and motifs, camerawork, lighting, pacing, editing and of course music, we can tell whether what we are about to see is a thriller, a romantic comedy, a crime picture, science fiction or more serious drama.

Each genre inherently has what has been called a horizon of expectation: thus in a romantic comedy — as generally in all comedy — we expect a happy ending. In a thriller, we expect that the hero will survive and triumph against all odds; in a serious drama, things will not necessarily work out for the best. In a magical fantasy, the supernatural is possible in a way that is not acceptable in science fiction, while in science fiction forms of technology that defy our current understanding of the laws of physics are allowed.

The idea of genre, like so much else, originates with the Greeks. The earliest genre was epic poetry, grand narratives inspired by the muse, speaking through the poet as if he were a medium. The earliest examples of epic to have survived, and thus the oldest literary masterpieces in the Western tradition, are Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, composed around 2700 years ago; there were other epics as well, but Homer’s were so far superior that they were the ones transmitted orally from bard to bard and then committed to writing a couple of centuries after their composition.

The next genre to appear was very different: lyric poetry, which was, and as a genre has remained, highly personal. It seems almost counterintuitive that lyric should have appeared before drama, but that is how it evolved. Lyric poetry flourished in the Archaic and early Classical period, but drama was the supreme form of the Classic period in the 5th century BC.

Drama is said to have emerged from choral songs, and thus from the dithyramb, another genre that was of hymns to Dionysus: the choral leader or coryphaeus is said to have stepped out from the body of the choir to impersonate a character. What exactly happened is a matter of scholarly debate, but the important thing is that almost from the very beginning, drama polarised into two main genres that have dominated our thinking about theatre ever since: tragedy and comedy.

Other theatrical traditions mix heroism, pathos and buffoonery. The Greeks separated them from the start: tragedy deals with serious matters, good, evil, crime and suffering, and its language is always noble and serious; comedy deals with the absurdities of human life, the dysfunctions of social systems and the frailties of human character, and its language allows for unbounded invective, slander, obscenity and scatology.

Genre is a fundamental category for understanding the history of art as well and once again has its origins in antiquity, although in practice the various genres had to be rediscovered and in some cases to reassert themselves, in the period from the Renaissance onwards.

To understand how and when the various genres emerge, how they were conceptualised and how they evolve or even collide with each other, especially in the modernist period, helps us to see individual works with far greater clarity.

The most familiar genres in art are probably the smaller or lesser ones, precisely because their specificity and boundedness are so clear to understand. We follow the British tradition in having a special fondness for portraiture, for example.

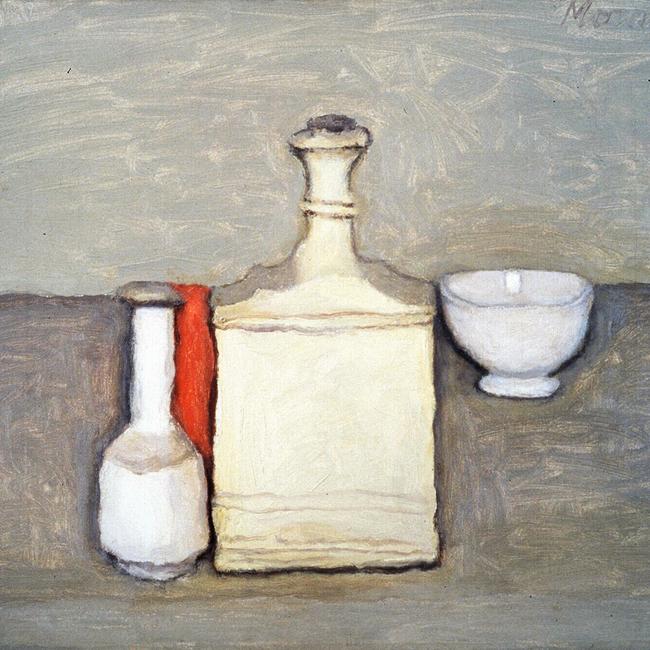

Still life is another that most people would naturally recognise: pictures of things, whether simple arrangements of bottles like Giorgio Morandi or elaborate compositions of flowers such as Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer’s Floral still life (1690s), which belongs to the Art Gallery of South Australia but is on loan to an exhibition at the David Roche Foundation (which is closed until further notice because of the current crisis).

But these genres, as well as the more important one, landscape, all ultimately represent forms that arose and then separated themselves from the central genre of Western painting, which was narrative or so-called history painting. This is the genre I will discuss in greater detail next week, and we will see that it not only mutates into many different varieties under different social and cultural circumstances but also explains the central place of figure drawing and the nude in Western art.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout