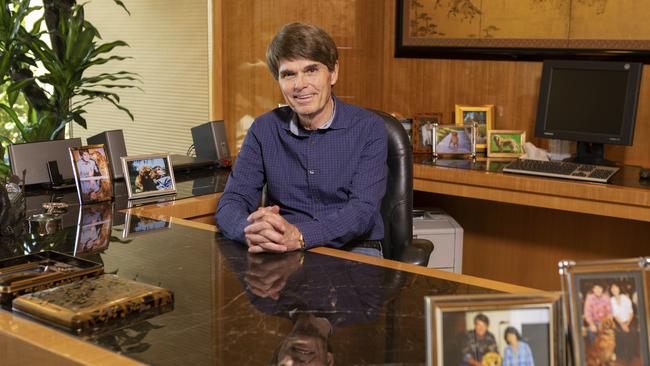

Dean Koontz, American novelist credited with predicting coronavirus

In 1981, Dean Koontz wrote about a deadly virus originating in a place called Wuhan. If his latest book is any guide to the future, we should all be worried.

Plague? That’s so yesterday. Artificial intelligence taking over the world? Ditto. Dean Koontz, the American novelist credited with predicting coronavirus, did the first in his 1981 thriller, The Eyes of Darkness, and the second in his 1973 bestseller, Demon Seed, which was filmed four years later with Julie Christie as Susan, a woman unwillingly impregnated by a computer.

As for being the Nostradamus of COVID-19, Koontz is sceptical. Yes, a brain-attacking biological weapon kills a lot of people in The Eyes of Darkness and yes, it is developed in the Chinese city of Wuhan in later editions of the novel (in the first edition, it starts in Gorky, in the old Soviet Union). But that, according to the writer, is just the sort of “happenstance” that happens when writers read a lot and write a lot.

“That’s what I always say to young writers,’’ he says in a telephone interview from the home in southern California he shares with his wife, Gerda, and their golden retriever, Elsa, who I mention for reasons that will be apparent.

“Don’t read just what you want to write. Read everything, because the more you pump into your head, the stranger the combinations that come out, and that’s only for the good.”

As for coronavirus, “my powers as a prognosticator have been greatly exaggerated, considering I can’t even accurately predict what I’ll have for dinner this evening’’.

We are speaking in late March, as Australia is going into pandemic lockdown. Koontz, 74, jokes that as a workaholic writer he has spent most of his life in self-isolation. He also has a “gut feeling” that the “through-the-roof panic’’ is “scarier than the virus itself”. He laughs and adds, “but we will see”.

There’s a bit of that gut feeling in his new novel, Devoted. When the baddie, Lee Shacket — and he’s one of the baddest baddies I’ve seen in a work of fiction — is asked whether what he has is communicable, he upbraids the government medical officer asking the question.

“So this is why you’re here,’’ he tells the doctor. “Ready to inflame the population with fear of a plague. You’re getting tiresome.”

What Shacket does have takes the end-of-civilisation stakes to a new level. He’s the former boss of a secretive biotech firm that told the world it was working on a cure for cancer. Behind closed doors, however, it was developing trans-species horizontal gene transfers. The plant burns down, incinerating a group of scientists, and Shacket is on the run.

It soon becomes clear that he is a “transhuman”, a man replete with the genetic material of other animals. “Human beings are just one of the many in the zoo. I am becoming king of the beasts,” he declares.

RELATED: The comfort of art in the age of coronavirus | Wringing advantage from virus adversity

Which beasts are encoded in him is not spelled out. Reading the book, I thought he was a bit zombie (the intelligent kind), a bit werewolf and a bit vampire. He kills people by eating them. Even autopsy room veterans struggle on seeing “the bite marks … had the curvature and tooth pattern of the human mouth”.

When I ask Koontz how on earth he imagined a man like Shacket, he is candid. His own father was a bit of a Shacket.

“I think sociopaths fascinate me because my father was a violent sociopath alcoholic. When things got bad in his life he would threaten to kill us all. It was best, he said, if we all just died. As a child, you hear that and it’s so awful and you wonder if your father means it.

“When he was later committed to a psychiatric ward, for making threats to people, he was diagnosed and I realised, ‘yeah, he did mean it’. That diagnosis opened my eyes to my whole childhood.”

It’s largely for this reason that the sociopaths and psychopaths in Koontz’s novels are bad to the bone. “I never want to write a novel in which somebody who is very dark and very evil somehow comes off as glamorous. I don’t want to glamourise evil.

“Wood, in my novel, is smart enough to know there aren’t monsters under the bed but there are monsters in the world. They just look like other people.”

Eleven-year-old Woody Bookman, a high-functioning autistic who has never spoken, is one of the people who might be killed by Shacket, or who might stop him. His mother, Megan, dated Shacket years ago. She married another man who worked for the company, who died in a helicopter crash, an “accident” that Woody is convinced was murder. Shacket, on the rampage, wants to conquer Megan and will kill and eat the “retard” to do so.

On their side is a golden retriever named Kipp, “70 pounds of muscle and bone”, and a former Navy SEAL who adopts him. Whether Kipp is 100 per cent canine is for readers to find out. All I will say is that he is a dog who thinks a lot.

When I say to the author that Stephen King has Cujo and he has Kipp, he laughs. He has had three golden retrievers, Trixie, Anna, both now dead, and Elsa. He thinks the spirits of all three are with him every day.

It’s less of a surprise, on talking to him, that the four epigraphs at the front of his new novel, from Franz Kafka, Maurice Maeterlinck, Mark Twain and Josh Billings, are each about dogs.

“I’ve thought so much about the human-canine bond,’’ he says, “and I’ve come to think that intelligence is spread throughout nature to a greater degree than we want to admit, or that we have not perceived yet.’’

Yet Koontz came to have a canine companion late in life. He and his wife have worked for almost 40 years with organisations that train assistance dogs for people with disabilities.

“They kept asking us to take a release dog — an assistance dog that can no longer do its work due to an injury — and we kept saying we were just too busy to have a dog,’’ he says.

“Then one day I said to my wife, ‘you know, we’re going to be saying we’re too busy until we’re 90’. So we decided to do it and it was the greatest thing we ever did. The first dog changed our lives in profound ways.”

For starters, it turned the author into slightly less of a workaholic. “I’ll never forget her coming into my office,’’ he says of the first dog, “and putting her nose under my wrist as I was working away on the keyboard. I thought it was funny, but she kept on doing it and suddenly I realised it was intentional. I had to stop work for a while and take her out.’’

Kipp’s thoughtful behaviour is one of the humorous sides of the book. It’s also funny that the members of an assassination-for-hire group take on working names such as Keith Richard and Roger Daltrey. This novel is a dark read, but it has moments of light.

“Part of this does also go back to my father, who was a very dark individual, mentally and emotionally, but who was also unintentionally funny. I saw that as a kid and I think it became a lesson to me as a writer. Horror and humour can go together.

“I remember in the early days, when I started introducing humour in my books, my publisher told me it would destroy my career, that nobody wants to read a book like this, that people can’t be scared and tense if you make them laugh.

“I thought that was wrong and I never stopped doing it … and finally they let me get away with it.’’

The readers agreed with the author. Koontz has written more than 100 novels since his 1968 debut, Star Quest, under his own name and a series of pen names. He has had 16 paperback and 14 hardback No 1s on The New York Times bestseller list. In total, his books have sold more than 500 million copies.

A former English teacher at a school in Pennsylvania, where he was born, he recalls another bit of advice he received early on in his writing career. “My first publisher, just when I was becoming a bestseller, told me my vocabulary was too large in my novels and I needed to reduce it to continue to be a bestseller.

“There’s a lot of common wisdom in publishing that isn’t very wise. I thought to myself, good heavens, I bet there are dogs with vocabularies of 500 words.”

Devoted, by Dean Koontz, is published on April 6 by HarperCollins (376pp, $32.99).