The comfort of art in the age of coronavirus

There are still means to keep in touch with art during this period of coronavirus-induced shutdown of galleries and museums.

After spending consecutive weeks with The Plague, The Road and Planet of the Apes, I decided last week that it was time to do something a little more cheerful. I saw an easy way and a less easy way to achieve this. The easy way was to read Tom Keneally’s new novel, The Dickens Boy (Vintage, 392pp, $32.99), which centres on the youngest of Charles Dickens’s 10 children and his time in colonial Australia, where he landed in 1868.

This is an ingenious, hilarious novel. It is Keneally at his most comic. The scene where near-17-year-old Edward Bulwer Lytton Dickens is introduced to the castration of lambs must immediately be inducted into the Australian literary hall of fame. I will write more about this book when it is released. For now, I just want to put it on your radar. Order a copy now.

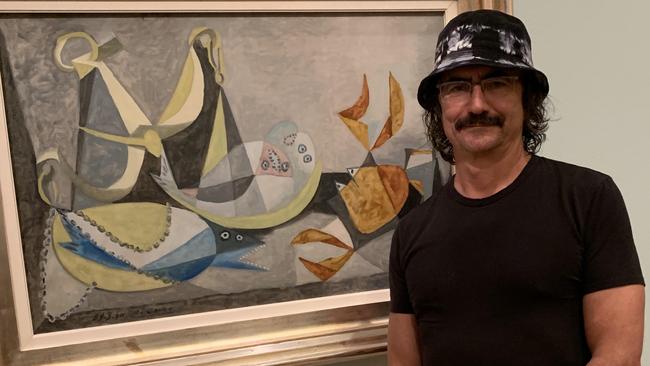

The less easy way was to drive to Canberra with my son and my mother to see the Picasso-Matisse exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia. We got in, and out, before the borders closed and the gallery shut its doors. My favourite painting in the show, one that nods to the name of this column, is Les Soles, in which Picasso’s two girlfriends of the time, Dora Maar and Marie-Therese Walter, are fish and he is a crab clacking its claws.

I realise recommending a closed art exhibition isn’t of much use, so I’d like to use it to draw attention to a 2016 book, The Art of Rivalry (Text), by US-based Australian art critic Sebastian Smee. And I want to go from the book to Smee’s thoughts on how we can still enjoy art in this era of self-isolation.

Smee used to be this newspaper’s national art critic, a job now occupied by the indomitable Christopher Allen. We are blessed to have had (Robert Hughes, for one) and to still have such world-class critics in this country. Smee, a Pulitzer prize winner for his criticism, is now art critic for The Boston Globe.

The Art of Rivalry is about artists who were friends (or perhaps acquaintances) and rivals. There are eight artists contrasted and compared side-by-side: Lucian Freud v Francis Bacon, Edouard Manet v Edgar Degas, Henri Matisse v Pablo Picasso and Jackson Pollock v Willem de Kooning. If Smee is the referee, he’s a fair one. He doesn’t pick winners.

He believes the real contest is “the struggle of intimacy itself: the restless, twitching battle, to get closer to someone, which must somehow be balanced with the battle to remain unique”. This struggle comes through in bold colours in the chapter on Matisse and Picasso, where the phrase “get closer to someone” should be seen in the artistic rather than personal sense.

The Frenchman and the Spaniard were very different men. One of Smee’s great strengths is that he writes about the artists as people first, painters second. You feel as though you are in the same room with them, with all their ticks and quirks. Keneally, too, does this brilliantly with the unscholastic son of the “laureate of humanity”, as one of the Australians dubs the great man.

In the climactic section of Matisse v Picasso, from 1906 to 1908, Matisse, a dozen years older, has three children. He “suffered panic attacks, nosebleeds and insomnia, and was plagued by insecurities”. Picasso had all the girls and “the kind of charisma that can dislodge even strong personalities from their earlier selves”.

It’s easy with the passage of time to forget that Matisse was streets ahead of Picasso for a while, in “achievement, in maturity and, above all, in creative audacity”. He could be magnanimous to the younger artist as he “had nothing to lose”. Picasso, on the other hand, grew “more determined to prove Matisse did, in fact, have something to lose” and “began plotting a picture that he hoped would establish his immediate ascendancy”.

What unfolded was “a drama unlike any in the story of modern art … a fight between two geniuses of invention … for a true and radical originality”. At stake, Smee concludes, “was election to greatness”. Being on that ride, with Smee as tour guide, is thrilling.

To finish, Smee has just written a piece on how to find art from the comfort of self-imposed quarantine. He mentions documentaries, books, podcasts, websites and a whole lot more. It’s valuable reading and you can find it online. “Art will save you,” he writes. “It’s the glue. It’s the machine that makes meaning. It’s beauty and truth. (And fear and sex and boredom.) It’s up there with the very best that humans have done.”

READ MORE: The List: authors’ and critics’ best books of 2019 | Ellena Savage; a young life against the grain