Matisse: the ultimate painterly pleasure at the Art Gallery of NSW

Matisse was temperamentally very different from Picasso, but his work reflects his own reaction to the same collective movement in the modernist pictorial imagination.

It is impossible to understand any art adequately without taking account of the history that preceded it and formed the conditions for its appearance, and that principle is – perhaps unexpectedly – even more applicable to the eruption of modernism at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century than to earlier periods. And that is because what happened in those years represented such a profound rupture with the traditions of modern art that had evolved in earlier centuries.

The most important development in the history of humanity in the last 500 years has been the emergence of modern science in Europe, which has now transformed the lives of everyone on the planet for better and for worse: it has brought us modern technology and medicine, but also and correspondingly the population explosion, unsustainable consumption, environmental degradation and the climate crisis.

The rise of modern art, from the time of Giotto and then, after the interruption of the Black Death, the renewed impetus of the 15th-century renaissance, played a crucial role in the formation of the new vision of the world that would emerge self-consciously in the 17th century as what we call the Scientific Revolution. The new painting was the imaginative instrument for articulating, in concrete shape, a new apprehension of the material world.

To the medieval mind, our world could be full of beauties, but ultimate reality was only to be understood from God’s perspective, as we see in the magnificent last cantos of Paradiso. The new painting started by looking more closely at this world and trying to convey the solidity of its figures and their existence in space. This was implicitly an assertion that there was reality to be seen from our point of view as well, and the system of rational perspective made that assertion explicit: the world could be rationally accounted for, could be complete and coherent, from the point of view of the human eye.

This system presupposed a number of axioms, including the separation of the subject mind from the object world – a precondition of scientific thinking – the distinction of bodies within the world, and their objective location in space. Of course there was much else in the new painting: objectivity served to make religious or secular subjects more vivid and concrete, and was qualified by the interest in feeling and expression. But the fundamental assumptions persisted until the 19th century.

Something began to change in the later 19th century, just as modern science was reaching the apogee of its triumph. One factor was a reaction against the reductive scientistic thinking known as Positivism, repeating the earlier romantic reaction against Enlightenment materialism. Another was the influence of photography, which seems to have driven the academic painters to pursue an extreme form of naturalism, while others, like the impressionists, turned instead towards a kind of subjective naturalism.

The impressionists were concerned with what the world looked like in its most immediate and ephemeral aspect, not with what it was like objectively. Consequently the solidity of the world was dissolved into patches of colour and all these patches of colour were registered as though on the same plane; this not only produced a certain flattening of space (which is why they were attracted to the flatter compositional designs of Japanese art) but also a depreciation of the distinction between figure and ground, in other words of the identity of bodies and of their objective location in space.

These tendencies are taken further in the work of the neoimpressionists such as Seurat, or post-impressionists such as Van Gogh and Cézanne, as different as they are in style and expression. Brushwork becomes uniform across the whole painting, instead of differentiating the treatment of closer or more distant things, or bodies of different natures and textures, such as trees and clouds. But Cézanne departs more openly from perspective itself: individual items in his still-life paintings, for example, are clearly seen from different angles and points of view, with no attempt to subordinate them to an overall perspectival logic.

This was the cue that led Picasso and Braque to develop analytical cubism in the last years before the Great War: a style characterised by the deliberate and, so to speak, experimental deconstruction of the whole logic of modern painting, both the coherence of one-point perspective and even the fundamental distinction between figure and ground, in other words between body and space.

Henri Matisse (1869-1954) was temperamentally very different from Picasso, but his work reflects his own reaction to the same collective movement in the modernist pictorial imagination, whose deconstruction of logic and rationality is of course as significant as a cultural event as the original articulation of that logical and rational vision. The darker potential of the anti-rational yearnings of modernism can be seen in some of the catastrophic events and movements of the subsequent century.

Matisse’s early painting La Liseuse (1895) is an effective starting-point for the exhibition: it is like the reverse of one of Vermeer’s compositions, in which still-life objects in the foreground so often form a repoussoir designed to lead the eye to the figure in the background. Here, on the contrary, it is the figure that serves as repoussoir and the collection of still-life objects in the background that constitute the visual focus, although there is very little concern to evoke any sense of space.

Hanging opposite this picture is a painting made a decade later, Les Tapis rouges (1906). It is the year Cézanne died, and certain stylistic features such as the flattened sideboard and the bunching of the drapery on the right unmistakeably recall his still lifes; but these echoes only serve to emphasise the profound difference of Matisse’s sensibility, above all his preference for colour over form. Instead of the white cloth which is so often the foil to Cézanne’s still lifes, Matisse has a bright green textile with a red pattern, possibly brought back from his recent trip to Algiers and Biskra in the desert; the sideboard is covered in another textile and the wall behind is hung with an Algerian kilim rug. Even the watermelon is chosen for the colour contrast of its bright green with the red cloth beneath.

Colour is supreme; the forms of the fruit and dishes are weak compared to Cézanne. But the really remarkable thing is the way that all of this is flattened into a pictorial surface with hardly any concern at all for space. We are almost at the point reached two years later in the famous Red Room (1908) in St Petersburg – not in this exhibition – in which the fabric of the tablecloth and that of the wallpaper behind merge into a single flat decorative pattern.

Why does Matisse choose to flatten his world like this? Art commentators in the middle of last century who assumed that flatness was in itself a good thing, part of the inherent destiny of the art of painting, could not really even see that this was a question to be asked. And yet every choice an artist makes is meaningful, and its meaning calls for explanation.

In this case the elimination of space has to be understood as the converse of the original construction of space in modern painting: the painting of space was concerned with constructing an objective and rational world, so its elimination is the retreat from objectivity and rationality (a simpler response than that of analytical cubism, which continues to struggle with body and space). But there is something more: the objective and rational world also served the human will, and ultimately the aim of mastery over nature.

Matisse is not only withdrawing from objectivity and rationality, but also from any kind of ambition of power or mastery. His outlook is more Epicurean, valuing pleasure above all, but not the violent and torrid desire evoked in Picasso’s work. Epicurus taught we should avoid those pleasures that are accompanied or followed by suffering, and seek instead stable and sustainable well being; Matisse’s work similarly expresses what we might call a quietistic hedonism.

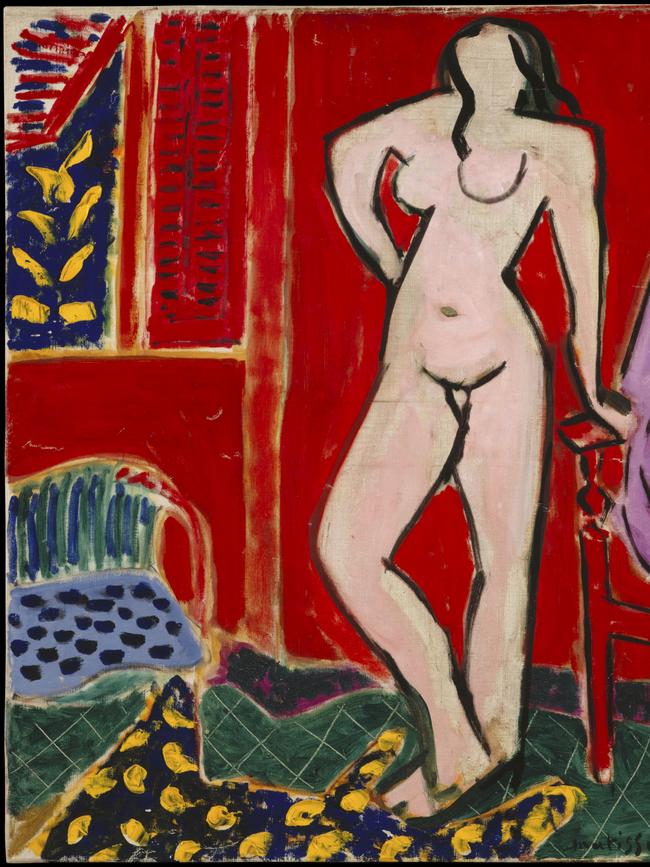

Inevitably, he was affected by the great events of history, and his paintings during the war are less serene. One of the most striking is Intérieur, bocal de poissons rouges (1914), in which we can feel the struggle to unite his inner world with the world of external reality, literally seen through the window. After the war, he settles back into decorative serenity in pictures like Figure décorative (1925-26), in which a monumental but expressionless nude sits in the midst of a luxuriance of exotic fabrics.

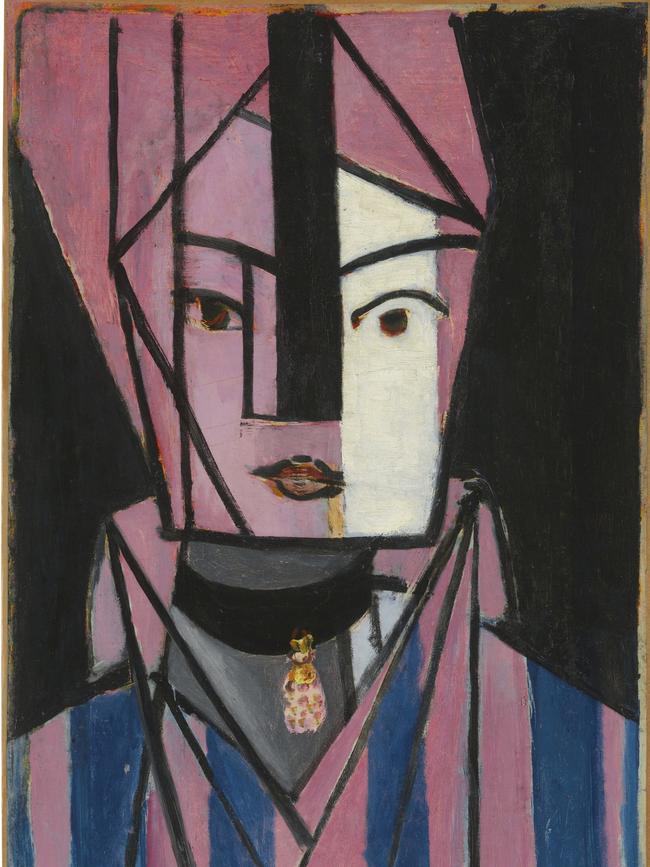

Matisse’s women, as I mentioned not long ago, could not be more different from Picasso’s. They are erotic or sensual in a general sense, and yet neither embodiments nor objects of explicit desire. They are rather images of a profoundly passive and receptive feminine dimension of being itself, like the Chinese concept of yin; they are usually reclining, somnolent or actually asleep, which makes the occasional portrait, like that of Baroness Gourgaud (1924) almost alarming in its alertness.

Whether in paintings or in the books of remarkable line drawings which I first saw as a child in my father’s library, Matisse’s women are not thinking, but they are being; they are images of simple presence, of stillness and calm.

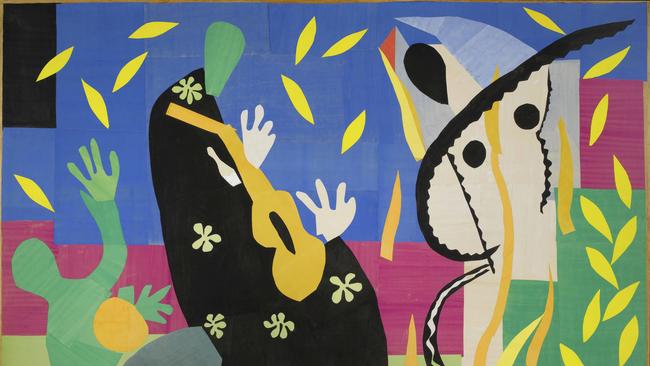

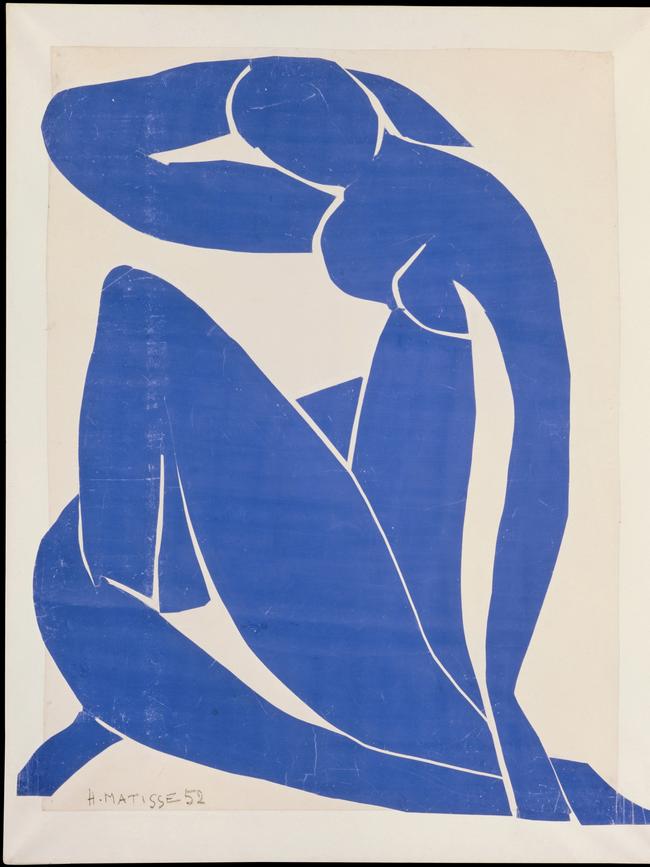

In his later years, after severe illness and the consequences of surgery limited his ability to paint, Matisse found a new means of expression in paper cutouts. There are remarkable images in the series published as a book with the title Jazz in 1947 – some of whose images must have deeply impressed themselves on William Kentridge – but ultimately the most mysterious of the designs are biomorphic shapes which evoke coral, seaweed and other marine forms.

These originated with Matisse’s visit to Tahiti in 1930, where he found the unfamiliar environment at once exciting, overwhelming and irreducible to pictorial expression. The most important part of his time there was a short stay at the remote and unspoilt atoll of Fakarava where he swam in perfectly clear water, dived among fish and corals, and looked at the abundant marine life through a glass-bottomed “diving box”.

It took a decade and a half for these impressions to mature, at the end of his life, into the simple but living forms that we see in the two panels Polynésie, la mer and Polynésie, le ciel (1946). Although one looks up to the sky and the other down into the depths, both are seen from the point of view of one immersed in the boundlessness of the water and surrounded by the proliferation of natural life. Space has no meaning and bodies are reduced to silhouettes; the viewing subject is not separate from but harmoniously involved in and at one with the amorphous but vital continuum of nature.

Matisse: Life and Spirit

Art Gallery of NSW to March 13

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout