Listen to the children

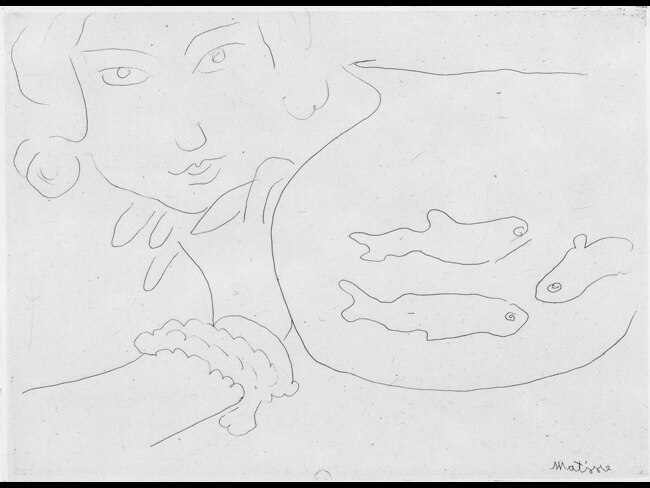

MATISSE'S strangely calligraphic images of nudes are implanted deep in my memory.

MATISSE'S strangely calligraphic images of nudes are implanted deep in my memory; my father had several volumes of them that fascinated and puzzled me as a child.

I recall him patiently explaining why these drawings were aesthetically superior to the more pedestrian but narratively effective illustrations in the books I was reading at the time but I'm not sure that I was entirely convinced. I was divided between admiration of the elegance of the line, in its spare yet luxuriant layout on the white page, and scepticism about their ultimate point.

I've learned since then that one should never ignore the reactions of children. They may be ignorant and untutored but they are seldom entirely wrong, whereas adults too often think as they are told. In any case, the comprehensive Matisse exhibition that comes to the Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane from the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris is an outstanding opportunity to enjoy and ponder the work of this remarkable and, as even a casual visitor can see, obsessive draughtsman.

We encounter the man himself at the beginning of the exhibition, in a small pen drawing from about 1900 that is all the more striking for being so stylistically unlike his mature work. Where we are accustomed to a fluent line that makes a virtue of freedom and even carelessness, here we have a repeated scratching that seems hesitant yet intent on accurate definition. A slight, bearded and bespectacled figure stares out at us myopically, with a distant rather than a searching gaze.

The look is altogether different in another self-portrait from perhaps a couple of years later. It is a drypoint, and the artist represents himself in the act of staring into the mirror, drawing his features on the plate: we sense the keenness of the investigation, though it is entirely turned back on itself, and the exacting definition of form and especially of the fall of light over the head.

This interest in light is already apparent in the earlier academic studies, two of which are included in the exhibition -- the first a masculine nude of about 1893 and the second a female nude of about 1900 -- as well as a study of an antique cast. In each of these three drawings, following a late academic simplification of earlier practice, Matisse has covered the whole sheet with a charcoal tone before beginning the drawing.

He has then marked the outline of the figure very lightly in willow charcoal as we can see from a kind of pentimento in the female figure, where he had first drawn the position of her left shoulder too high and then thought better of it. Working from the midtone, Matisse has then built up the shadows with more charcoal and finally established highlights by erasing the original ground in parts, revealing the white of the paper. (This is why he was not able to rub out the mistaken shoulder line.)

From the earliest of his independent drawings, however, it is clear that Matisse is drawn to line and contour rather than to volume and the expression of tactile experience in graphic form; what art historian Bernard Berenson at about the same period called "tactile values" in his characterisation of the styles of the Renaissance. If Picasso's emphasis is tactile and sculptural, like that of Masaccio or Piero della Francesca in the 15th century, Matisse recalls the linear and ornamental inclination of Botticelli.

In the little figure etchings for which his wife posed, such as La Pleureuse (1900-03) we can see him already concerned to discover the contour lines that flow from one part of the body to another, particularly such conspicuous examples as the alternation of convex and concave lines that make up the legs, rather than to focus on the core masses and volumes of the figure; that is, the rib cage and pelvic girdle. The result, predictably, is that while the limbs generally flow freely, those central volumes are subject to an elongation and distortion that anticipates aspects of his mature style.

In a slightly later portrait of his wife, Mme Matisse in a Kimono (1905), we discover another part of his sensibility: the love of pattern that is so ubiquitous in the paintings and is often manifested in the fabrics of clothes, wallpapers, upholstery and rugs. As always, technique is significant: the work has been sketched in pencil, then drawn in pen, emphasising outline and pattern.

There are a few drawings that show the attraction of cubistic experiments and primitive arts but Matisse's instinctive direction is elsewhere. There are deliberately rough woodcuts from the fauvist period (the shortest movement in the history of art, confined to a couple of summers) and Matisse's distinctive calligraphic figural idiom is already fully defined in the 1913 lithographs.

In the most successful of this series, the Woman in a Three-Quarter View, the whole belly is described in a single sweeping curve: as in his later work, speed and the flow of the line count for more than anatomical accuracy. In a portrait of the same year, Visage a la frange, the face is reduced to only those features that can naturally be expressed in linear terms: eyebrows, eyes, nostrils, lips. Leonardo, of course, had dissolved these lines in sfumato, considering them illusory interruptions to the continuity of volumetric modelling. But Matisse is not interested in modelling or volume and reverts to a purely linear, contour interpretation of the head.

After the war, Matisse turned to the study of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres -- this was part of a general European tendency to return to classical sources after four years of conflict and horror, which ended for the defeated in social chaos. His choice is a significant one, for Ingres, although considered the arch-conservative leader of the academic tradition, was really a more complicated artistic personality. And although Ingres was famous for declaring that drawing was the integrity of art, his own approach to drawing, especially the figure, was characterised by a love of contour and a surprising neglect of volume and anatomy in paintings such as the Grande Odalisque (1814).

For Matisse, the new neoclassical approach to drawing was undoubtedly beneficial, for the linear style he had developed before the war had nowhere to go except to slide into perilous repetition and mannerism -- his later work is mannered enough as it is.

But the drawings of these post-war years and of the 1920s are not facile or repetitive. In a work such as The Plumed Hat (circa 1919), we can sense the fascination that anyone who has tried to draw will know: the realisation that the face represents a thousand formal problems, and that it is composed not only of a shorthand of contours but of the infinitely subtle modelling of forms around the eye, the lid, the brow, with lines, folds of flesh and pools of shadow that become only more complex as you examine them.

What is appealing about this drawing and others of the period is to feel the artist actually thinking and, as in all real thinking, encountering that disconcerting sense of unfamiliarity and strangeness, as though attempting something for the first time; a strangeness that leads here and there to the kind of clumsiness that is attendant on discovery. There are a couple of more finished and more confident drawings of 1924 and 1925, the Grande odalisque a la culotte bayadere and the Odalisque on a Blue Cushion -- both of which are related to contemporary paintings. They are impressive studies of women but, perhaps precisely because they are so thoroughly worked out, they raise the question of the subject of Matisse's art.

The term odalisque directly evokes Ingres, but more generally suggests an oriental courtesan or some contemporary equivalent. Idleness, sensuality, availability are all part of the association of ideas.

Yet, surprisingly enough, there is nothing at all sexually arousing or provocative about these girls. There is no spark of flirtation or offer of seduction, not even the steady businesslike gaze of Manet's jaded demi-mondaine in the Olympia. It is hard to imagine less sexy nudes. All the artist's attention is devoted to the composition and the variation of attitude between the model with arms resting on the chair in one case and raised over her head in the other.

Matisse is more interested in the way light models the form of the breast when it is lifted in the latter pose or settles into a shaded concave slope in the former; he dwells on this phenomenon with the disinterested curiosity of a botanist examining the morphology of a plant form.

And it does indeed seem that woman -- his almost exclusive subject, just as it had been Ingres's most successful -- stands for the life of nature, as though the female form were the most interesting, complete and almost self-sufficient embodiment of all the manifestations of natural life. But in the process Matisse's women transcend the level of erotic response and are closer to those fern and jellyfish forms to which the artist resorted in his later years.

There is a photograph of Matisse with the model years later (1939) in which the now elderly artist sits in a white painter's smock that looks almost like a lab coat, attentively drawing a shapely girl who lies naked on a sofa close to him. But one doesn't feel that he is trying to get close to her; rather, strangely, that he is trying to get further away. Why should this be the case? Because although no doubt aware of the girl as an object of desire, he is trying to see past that and to turn her into a pattern emblematic of life.

It is interesting that Marcel Duchamp criticised Matisse for returning to the indulgent 19th-century practice of painting nudes stripped of the poetic or indeed conceptual significance with which they had been endowed in earlier centuries. There is little doubt Matisse became at times repetitive and facile in the later graphic works, and a closer examination of the deluxe illustrated books of poems shows that the drawings he provided are not always particularly apt accompaniments to the text, but this is not all there is to his work.

In the end, it is a quality of life that animates his line, as though he were trying to see past the material solidity of things to the inner movement of their vitality. And this is the great theme we can see in his most important works, from the early Joie de vivre (1906) to the Dance murals executed for Dr Albert Barnes of Philadelphia, and even the late cutouts in which the life of a circus or the ebb and flow of the oceanic world are evoked through paper silhouettes.

Matisse: Drawing Life

Gallery of Modern Art, Brisbane, to March 4