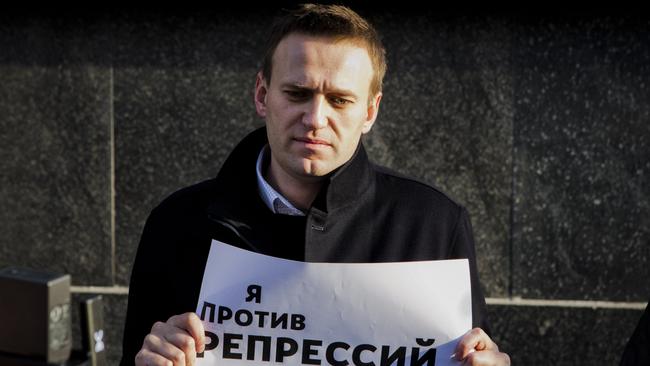

‘In reality, Alexei Navalny was in real pain.’

One year after the death of Alexei Navalny in a Russian gulag, photographer Evgeny Feldman recounts an earlier attack on the leader of Russia’s democracy movement, when a caustic green liquid was used.

On March 20, 2017 a mantle of snow was draped over the Siberian city Barnaul, as Russian opposition leader and corruption fighter Alexei Navalny arrived to meet his supporters. Navalny was touring Russia ahead of the 2018 presidential election in which he planned to stand against the incumbent, Vladimir Putin.

It had been a dirty campaign, even by the Kremlin’s standards.

Evgeny Feldman, a prominent photojournalist who travelled and worked closely with Navalny for more than a decade, recalls: “The government at the very beginning of the campaign decided to harass Navalny as much as possible; harass him away from campaigning. It was absolutely crazy … when we travelled by train, there were some goons waiting at our exact train platforms and everywhere they were throwing eggs at us or trying to throw some punches. And that happened in city after city.’’

On that chilly March day eight years ago, the opposition leader was walking from his car to his team’s headquarters in Barnaul when an unknown assailant squirted a liquid – a caustic antiseptic – over him, turning his face and hands green. Feldman arrived on the scene minutes later and he says that particular antiseptic is “mostly used for medical purposes … It burns your eyes, burns your mouth, nose, whatever is exposed. It’s really unpleasant.’’

In the aftermath of this unprovoked assault, “Navalny was I think the most erratic I’ve ever seen him’’, says the photographer. With his face and hands still an unearthly green, and still burning, he persisted with taking questions at a press conference. “On the fly, they (Navalny and his team) decided to laugh it off; to show the Kremlin that it is not working. But in reality, Navalny was in real pain.’’

Feldman watched as the politician ran back and forth between the press conference and the Barnaul headquarters’ toilets, in a desperate attempt to wash the burning antiseptic from his eyes and skin. He was “kind of half-naked when he was in the toilet, washing his face … He could have just closed the door on me, but he did not,’’ says Feldman, who was then working part-time as an independent photographer for the opposition leader’s campaign.

The resulting image, titled The Mirror, makes palpable Navalny’s fear and vulnerability on that traumatic afternoon – and was a harbinger of what was to come for this infinitely courageous man, the relentlessly persecuted face of the Russian democracy movement. (A similar attack in Moscow weeks later severely damaged one of Navalny’s eyes.)

The Mirror – and two other images related to the 2017 Barnaul attack – feature in a landmark exhibition of Feldman’s photographs at Melbourne’s Goldstone Gallery, which will open on Wednesday (February 12).

Called This is Navalny, the exhibition promises to reflect “the indomitable spirit of a man who dared to confront authoritarianism, offering a profound and intimate portrayal of his life, activism and legacy’’. The timing of the show could hardly be more poignant: it commemorates the first anniversary of Navalny’s death at the Yamalia region’s Penal Colony Number Three, located above the Arctic Circle, on February 16, 2024.

He was 47; husband to Yulia, a father of two – and Putin’s most vocal critic. In a catalogue essay, art history academic Dr Ksenia Radchenko writes that Feldman’s images offer a powerful visual chronicle of “Navalny the activist and Navalny the man’’. She adds: “Through these photographs, Feldman navigates the intersection of political resistance and personal sacrifice, offering a nuanced portrayal of Navalny’s enduring legacy.’’

This tribute to Navalny is the inaugural show at the Goldstone Gallery, which has been established by gallerist Diane Mossenson and her husband, Dan, as a platform for hidden or suppressed voices. This follows the recent wave of anti-Semitism targeting Jewish creatives as tensions rose over the Israel-Gaza conflict.

Feldman will visit Melbourne for the opening, and is speaking to Review from Latvia, where he now lives in exile. The 33-year-old photojournalist – bearded and with a distinctive Mohawk – has had his work published in outlets including Time, Bild and The New Yorker, and from 2011 until 2022, he documented Navalny’s rise from a rabble-rousing anti-corruption blogger to an internationally admired opposition leader.

“The level to which Navalny is entangled with my life is insane,’’ says the photographer, who corresponded with the anti-corruption campaigner after he was jailed and took hundreds of thousands of images of him. In vivid detail, Feldman describes how the 2017 antiseptic attack was the first time he had seen Navalny’s composure crack to reveal two sides of the politician. “Navalny backstage and Navalny onstage were never very different,’’ he says. “But that moment was one of few where I’ve seen him acting differently. Putting on a brave face to talk publicly and then being really vulnerable, trying to wash that substance off.’’

He recalls how Russian authorities shut down another Navalny campaign event later that day. “With his face still green’’ the presidential candidate pivoted to address supporters on the street, effectively daring police to arrest him. Recalls Feldman: “It was very, very Navalny. I think this was the core part of his modus operandi. If Navalny was restricted from doing something, you can bet it was exactly the thing he would do; and he would do it in a most provocative way’’.

Tragically, the 2017 assault was a grim dress rehearsal for what was to come. In 2020, Navalny was poisoned and became gravely ill during an internal flight in Russia. The plane made an emergency landing in Omsk, where he was treated before being flown to a Berlin hospital, where he eventually recovered.

Experts later concluded he had been poisoned with Novichok, a military-grade nerve agent developed by the former Soviet Union. Despite this, in 2021 Navalny returned to Russia, where he was immediately arrested and imprisoned on politically trumped up charges.

He was sent to several penal colonies including, finally, the Siberian gulag. Navalny’s death was condemned around the world, including by then-US president Joe Biden who said: “Putin is responsible for Navalny’s death.” German Chancellor Olaf Scholz recalled talking to Navalny about the “great courage” he showed in returning to Russia after the poisoning attack. “He has now paid for this courage with his life,” said Scholz.

The Kremlin denied involvement in Navalny’s death, and called Biden’s remarks “absolutely rabid’’.

Roughly one year ago, a colleague woke up Feldman to tell him Navalny had died. Over the next few hours, the photographer didn’t have time to react, or mourn: “I just went to my laptop and started to comb through photos. So that whole day I was occupied.’’

Afterwards, however, “I was crying for a few weeks. And I think that for me, it’s all very complicated and intangible’’. On most days since Navalny died, he has searched his vast photographic archive, responding to requests for articles, images and exhibition material. “It’s quite painful,’’ he says.

Interestingly, he reveals that Navalny “was never actually considering staying in Germany (long-term)’’. His commitment to his cause was so unwavering, “it was just the natural thing (to return to Russia)’’.

As soon as the opposition leader landed back in Russia, a rigged trial was conducted at a police station so he could be jailed immediately – and once again, Feldman was there. The trial lasted about eight hours “and for the whole time I was standing next to the fence of this police station’’. The snow came up to the photographer’s knees. He was so cold, “I started to Google the symptoms of frostbite’’.

When Navalny was finally brought out of the police station, the authorities did their utmost to impede the photographers. There was pushing and shoving but the freezing photojournalists got their shots. “It was pretty dramatic’’, says Feldman.

The pair corresponded regularly while the activist was incarcerated. The Goldstone Gallery’s website includes excerpts from letters Navalny wrote to Feldman from different penal colonies. “We wrote to each other extensively while he was kept in unbearable conditions. Navalny remained optimistic, encouraging me and others to act and not succumb to despair,’’ Feldman says.

Initially, Navalny was sentenced to a penal colony 200km from Moscow and allowed to receive letters sent online. These letters – always checked by censors – could be exchanged relatively rapidly. “In Russia, there is a culture of talking to political prisoners,’’ Feldman tells Review.

“And everyone who does that knows that political prisoners want to use these letters as a window to the normal life. That is why our talks with Navalny when he was in prison … were about London and curry and concerts and stuff like that.’’ In one letter, he told Navalny about a visit he, his wife and exiled Russian punk band members made to a punk music festival in Italy.

Navalny responded with a three-part message: “Say hi to all the punks. F..k war. Hearts A (for Alexei).’’ That message is now tattooed on Feldman’s arm and he stresses that “miraculously this particular censor did not cut this out’’. The Siberian gulag’s censors were more restrictive and used traditional mail services, so communication was slower – so much so, Navalny’s letters arrived at a Moscow address the exiled photographer still used, for two months after his death.

Overseen by Goldstone curator and Jewish artist Nina Sanadze - a recent target of anti-Semitic attacks - the exhibition spans four gallery rooms. Feldman’s images are grouped thematically: one room features large-scale portraits showing Navalny’s power and charisma as leader of the Russian democracy movement. Another offers insights into his family and backstage lives, while a third gallery room depicts the rallies and huge public demonstrations the anti-corruption campaigner inspired in his homeland.

The final room depicts the attacks, arrests, poisoning and prison sentences Navalny endured before he died. Sanadze says the exhibition’s title, This is Navalny, “references his own words — Alexei often began his speeches with, ‘Hello, this is Navalny’.”

During his long association with Navalny, Feldman captured everything from his subject’s quiet moments of reflection, to him eating packet noodles on the campaign trail late at night. He bore witness to his ability to energise massive crowds of protesters and to his persecution as he stared out at the world from behind bars or raised his handcuffs in a bemused way while sitting next to a fur-hatted, bearish police officer.

Through his lens, he also witnessed intimate moments: Navalny’s apartment after it was ransacked by security agents, or the politician talking to his young, frightened son after the family was ejected from a Moscow rally. Feldman recalls: “The little guy started crying. Alexei was kind of strictly talking to him not to be afraid of the police, not showing the police their weakness.’’

In 2022, the photographer was forced to leave Russia after the Putin government started criminal proceedings against individuals with connections to Navalny. He and his wife “were scared that I will be arrested,’’ he says.

A few days after this interview, Feldman reveals that “the Russian government started a procedure to put me on trial for having a relationship with Meduza”, the banned news outlet he works for in Latvia. “Hell of a coincidence,’’ he adds dryly.

Feldman wasn’t always a Navalny admirer. In a piece he has written for the Melbourne exhibition, he admits that when he first encountered the agitator in 2011 as a young photographer working for a liberal Russian newspaper, “I hated the guy’’. Navalny was then “a scandalous blogger” and “worse still, he was engaging with nationalists … He seemed too radical, too active, too political!’’ Within months Feldman had changed his view, as Navalny’s attempts to unite Russian liberals and “angry internet users’’ into an effective opposition proved successful.

Feldman then worked for Navalny’s campaign, sensing that he was “someone I needed to be near to witness history’’. He maintained his editorial freedom and “he allowed me as much access as I wanted’’.

He is currently a photo editor at Meduza, the independent Russian news outlet that has been banned by the Kremlin and operates from Latvia.

“We are completely shut down in Russia. If you live in Russia and you give an interview to us, they will send you to prison. This is absolutely how it works,’’ he says with a rueful chuckle.

“It’s insane. They ban us, but we are able to make our stories available for Russians and we cover the (Ukraine) war extensively. We cover Navalny. And we are able to pierce the censorship of Russian government.’’

His photo books and a self-published magazine, SVOY, have been crowd-funded and his images from Navalny’s 2017 and 2018 presidential campaign have attracted more than 1.5 million views online. Some went viral and reached a viewership “an order of magnitude higher”.

Feldman’s photographic albums and assignments have ranged across subjects as diverse as Navalny and other Russian dissidents, mass protests in Ukraine, football, open heart surgery, Donald Trump, and Chicago’s stunning skyline. The Goldstone exhibition is his first solo show and this reflects, he says, how it is impossible to mount exhibitions of political material in Russia.

Asked what Navalny’s legacy will be, Feldman’s response is complicated. He says: “I think it differs a lot for different people. There’s a global part of this legacy; he is obviously a person in this line somewhere between Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King and Nelson Mandela – all those people who symbolise the struggle for freedom for all people.’’

However, “it is really tragic’’, he argues, that the Navalny legacy is not stronger inside Russia, where Putin’s propaganda machine has rendered much of the population politically passive.

“I know that I and millions of other people are thinking about him every day,’’ he says. “There are millions of Russians who are not thinking of him at all. And that’s very sad.’’

Then there is a final part of the legacy that is “much more personal for me, something that is much less connected to Russia or politics, but is about perseverance and the belief and energy he had. “In those letters – (sent) from f..king prison – he was encouraging me not to be gloomy, to be optimistic, to do something. I cherish that a lot. For me personally, that was maybe the most important part. To not give up.”

This is Navalny opens at Melbourne’s Goldstone Gallery on February 12.

Pictures: Evgeny Feldman

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout