Life before modern anaesthesia, antiseptics and antibiotics

The entrance to the exhibition is designed as a doctor’s waiting room. Then you walk down corridors leading into various consulting rooms, representing different areas of medical science.

The history of medicine is a vast and fascinating topic, and it is a credit to the depth of the State Library of NSW’s collection that it is able to mount a survey as extensive as this. But it is at the same time a reminder that while a state library has a special responsibility for collecting material relevant to the history of that state, it also has a broader duty to acquire works that set the local material in perspective; otherwise it risks being no more than a bigger version of a local historical society, lost in the undergrowth of parochial preoccupations.

What perspective means is limited only by the intellectual ambition of the institution; for a library in NSW, it means first the history of Australia, then that of Britain, but more broadly of Europe, which in turn takes us, on the vertical axis of history, back to antiquity, and on the horizontal axis of geography across all the civilisations of the Eurasian continent.

A great library should build as comprehensive a collection as possible of the literature of humanity, but perhaps particularly of the most important books that have been published in the past five centuries, since the invention of printing. These are works that first revolutionised the dissemination of existing knowledge and then became the vehicles of the new discoveries and ideas that produced the world we live in today.

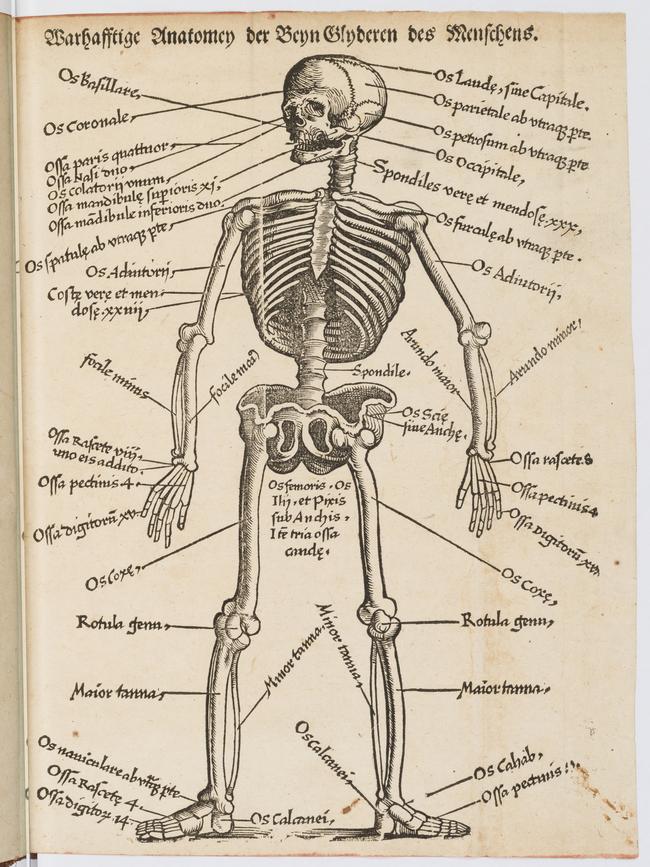

One such book is Vesalius’s extraordinary De Humani corporis fabrica, published in 1543. Vesalius was a brilliant young Fleming who began with the idea of editing a new edition of the canonic Greek author Galen and ended up producing the first great atlas of human anatomy, a direct heir to the anatomical research of artists like Leonardo. This is a book currently represented in the exhibition by a facsimile, but soon to be replaced with a fine copy of the original.

The entrance to the exhibition is designed as a doctor’s waiting room, where a short introductory video is played, before we walk down corridors leading into various consulting rooms, representing different areas of medical science. Unfortunately, the clinical design of the waiting room and corridors jars with the ambience of the individual rooms.

The introductory video attempts to explain the ancient theory of the four humours in a popular manner, but ends up being too hasty and at times inaccurate; above all, it fails to convey the real breadth, depth and interest of this long tradition of thought.

We should never be dismissive of great minds of the past because, by an accident of birth, and through no intellectual effort of our own, we have inherited knowledge they lacked.

The theory of the humours, elaborated in Greece in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, was based on the idea of a correspondence between the structure of the world and that of the human body.

The macrocosm was composed of four elements: earth, air, fire and water; the microcosm of the body was similarly made up of four matching “humours”: blood for air; yellow bile or choler for fire; phlegm for water; and black bile for earth. When these humours were in equilibrium, the body was healthy; when they were out of balance, it was sick.

But the theory had a much broader application. Even within the limits of good health, some humour may be preponderant in each of us, and this will determine our character. Those with a preponderance of blood will be “sanguine” and cheerful; choler will produce the “choleric” personality, prone to anger; phlegm the “phlegmatic” man, not easily moved; and black bile the “melancholic”, prone to inwardness, reflection and sadness.

This list alone gives some idea of pervasiveness and persistence of the tradition in our everyday language. And there are many other examples: apart from “humour” in all its connotations, there is “temperament”, which refers to the mixture of humours in each of us; or “complexion”, which is the facial colouring characteristic of each temperament – red for sanguine, sallow for melancholy, and so on.

Our primary temperament is in turn overlaid by the temperaments typical of age: everyone is more sanguine in childhood, choleric in early adulthood, melancholy in later middle age, phlegmatic in old age.

The seasons have the same associations, from spring to summer to autumn to winter, and so do the times of day: thus our basic inclinations are either mitigated or exacerbated throughout the unfolding of our lives, as well as by cyclical changes in the course of a year or indeed of a single day.

Thus even the melancholy will be more cheerful in childhood and will settle more deeply into their inherent nature in later life. In a case I studied in detail some years ago, Caravaggio, who was a choleric man, died at midday in midsummer, a time when his inherently fiery nature was aggravated by prevailing conditions.

Understanding someone’s inherent nature was critical to treating them for any illness, for just as we all know, not everyone responds in the same way even to the same cold they catch from another. There is in fact today a greater recognition of the need to treat a whole patient, not merely a disease, as though that disease would express itself in exactly the same way in all cases.

Ultimately, of course, the humoral model considered disease as arising from an internal disturbance in the homeostasis of the body, and this is still broadly how we understand non-infectious illnesses like cancer, heart disease, diabetes, auto-immune illnesses, etc. But in fact – contrary to the suggestion in the video that the old model reigned unquestioned until the 19th century – the humoral system was under serious challenge from the 16th century, with the arrival of syphilis from the new world.

It was Fracastoro, the man who gave syphilis its name, who first suggested that we catch an infection like this through some kind of “germ” – like a seed that takes root in our body.

Others followed him; the alternative theory for certain kinds of diseases – those we now consider infectious – was not fully explained and vindicated until the work of Louis Pasteur, but both theoretical texts and practical applications like the mercury treatment of syphilis from the 16th century, Harvey’s discovery of circulation in the 17th, or the prevention of scurvy through diet and the discovery of vaccination in the 18th, are evidence of new ways of thinking about medicine.

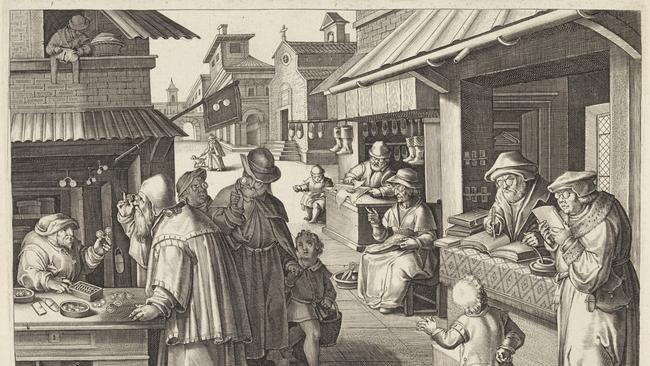

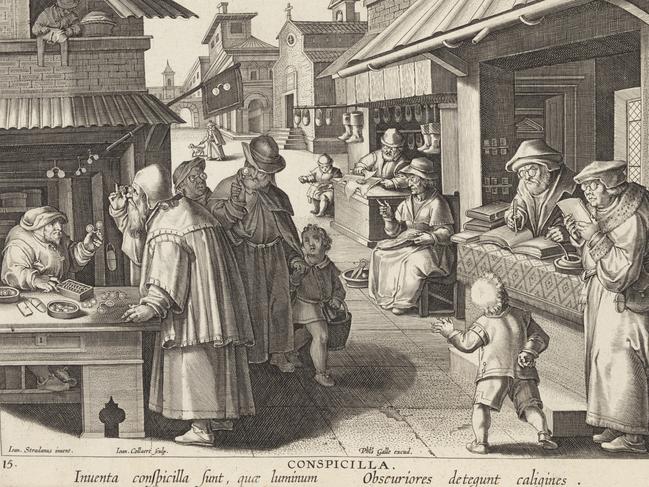

A great deal of ancient and pre-modern medicine made use of plant remedies, and one very interesting section of the exhibition is devoted to herbal treatises. One of the more impressive volumes, from 1532-36, has a cover page covered in tantalising mythological images relating to healing – represented by Apollo, his son Aesculapius, the god of medicine, in modern dress as a doctor, and Heracles, seemingly also enlisted as a conqueror of diseases – as well as the gardens of Adonis and of the Hesperides.

Many plants do contain active ingredients, and it was the great 16th century medical author Paracelsus who declared that the difference between a remedy and a poison was a matter of dosage.

The discovery of the new world gave access to new plant ingredients, and there is a section of the exhibition dealing with new materials from South America, including the coca leaf, the chinchona tree from which quinine is extracted, and even a wood called guaiacum which was thought to be a remedy for syphilis.

Surgery was naturally less common before modern anaesthesia, antiseptics and antibiotics. One of the most popular minor interventions was bleeding, for cases when an overabundance of blood was considered the problem (this is said to have caused the death of Raphael, after a misdiagnosis of his condition).

Surgeons would also deal with wounds from war or other causes, and Galen himself acquired an extraordinary reputation in his youth for successfully stitching up wounded gladiators.

In the age of artillery, from the 16th century, soldiers suffered new kinds of wounds, including the shattering of bones which required amputation, a gruesome and agonisingly painful practice, illustrated in the exhibition in a woodblock of 1540. This was when the French surgeon Ambroise Paré invented the tourniquet, preventing patients from bleeding to death.

Proper anaesthesia did not come until the invention of chloroform in the 19th century, but in the meantime, the greatest risk in surgery was infection; the importance of hygiene was only gradually recognised during the course of the 18th century.

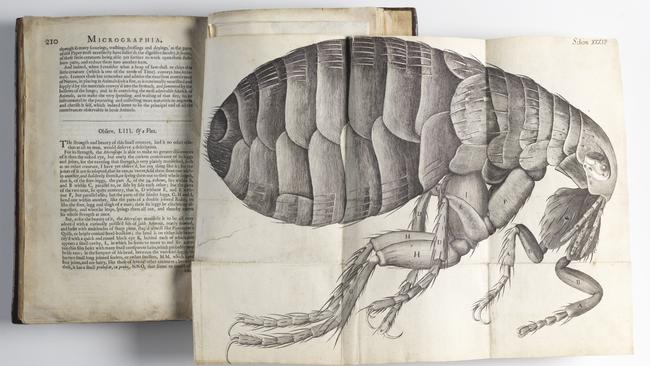

The bacteria that were responsible for infection had first been seen with the invention of the microscope in the 17th century, as had other microorganisms, and there is a fascinating plate from Robert Hooke’s Micrographia (1665), showing for the first time what moulds really look like – “nothing else but several kinds of small and variously figur’d mushrooms”.

But the good and bad effects of these micro-organisms would not be fully understood for another two centuries or more.

In the meantime, trade and travel had always been vectors for the spread of disease, most notoriously the plague, but the opening up of global population movements with the age of exploration led to a corresponding spread of infectious diseases, especially to or from places that had always been isolated by previously untraversable oceans.

Syphilis came to Europe, and in exchange smallpox and other diseases, endemic in Eurasia, devastated populations in continents that had never known these scourges.

Long sea voyages brought their own medical risks, especially scurvy, which was effectively dealt with by experiments in diet during the 18th century. There are several documents here on the topic, one of the most interesting of which is Sir Joseph Banks’s account of his own experience in his diary, closely monitoring himself for symptoms and changing his diet or medication accordingly.

Finally, among so many notable documents and displays, there is a section on mental illness, with a remarkable group of 19th century works, from suicide and its antidotes (1824) to the treatment of the insane without mechanical restraints (1856), which collectively seem to suggest an increase in the incidence of insanity in the harsh and alienated conditions of the Industrial Revolution and the growth of great cities.

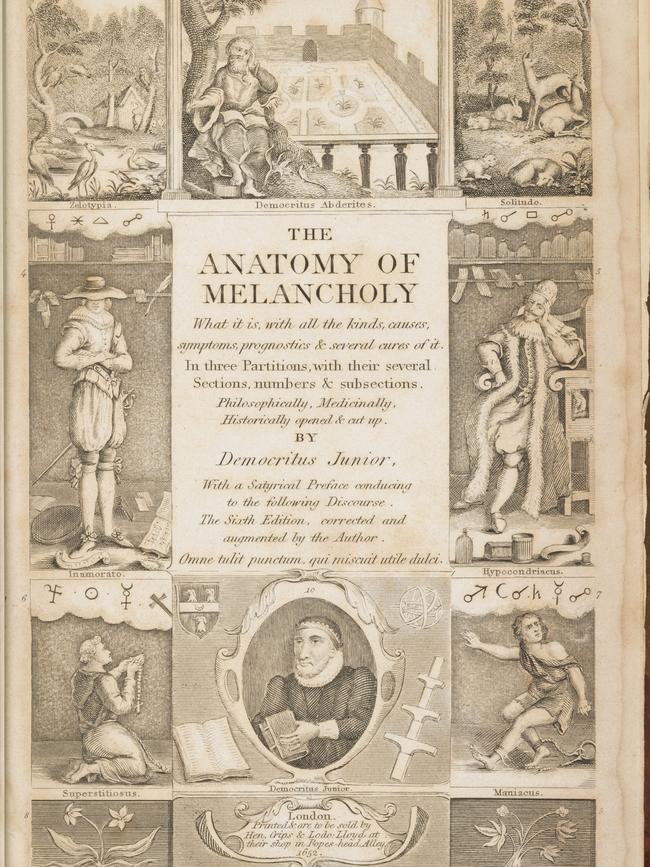

The display also includes Robert Burton’s classic The Anatomy of Melancholy (1652); the term is today largely replaced by “depression” as a psychological diagnosis, but has a fascinating history that has been studied by such scholars as Erwin Panofsky and Rudolf Wittkower, especially as artists and intellectuals were traditionally considered more prone to the condition.

In the Renaissance, it was discussed by Ficino, who proposed remedies; in the romantic period, it was celebrated by poets like Keats in his Ode on Melancholy. But like all the conditions and temperaments of the old humoral system, it belonged to a holistic world view in which the psychological was inseparable from the physical and physiological.

Kill or Cure? A Taste of Medicine, State Library of NSW. Christopher Allen is a member of State Library Council.

Kill or Cure? A Taste of Medicine

State Library of NSW

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout