Jan Utzon visits the Sydney Opera House for its golden anniversary

The eldest son of architect Jorn Utzon tells why his father never returned to Sydney after he could not finish his masterpiece.

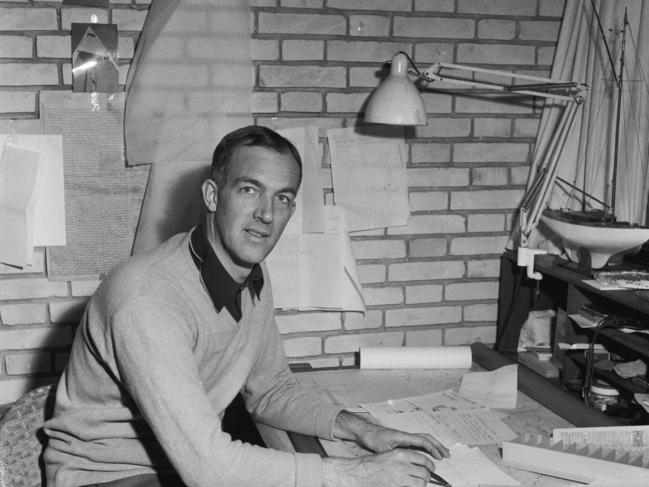

Jan Utzon cannot forget his first visit to the Sydney Opera House – although, at the time, the 18-year-old was excited just to be in Australia. The eldest child of architect Jorn Utzon arrived with the rest of the family from Denmark in early autumn 1963 and was often at the construction site at Bennelong Point.

Sixty years ago, the Opera House was not yet the Opera House. The concrete for the podium base had been poured, but there was no pink granite cladding, and the famous sails that have become a globally recognised symbol of Australia were a vision yet to be realised.

“I remember walking around in my sandals, no helmet, just T-shirt and shorts,” he says. “And it was the same with the workers here. There were no security ropes, they just climbed around like monkeys on the building site. I had never experienced anything like it.”

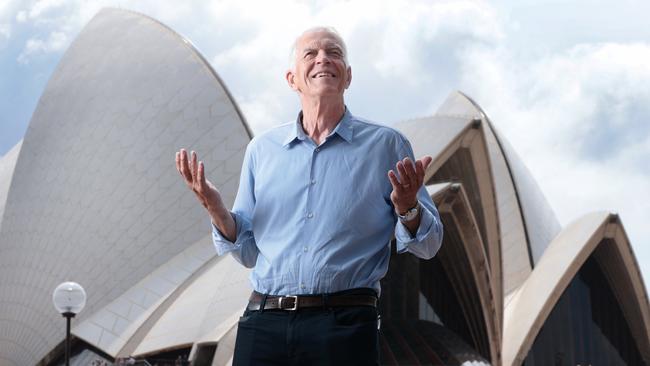

Utzon, 79, is a great Dane just like his dad. Tall and slightly hunched, his face is creased with laugh lines and tanned from the fortnight’s holiday he’s enjoyed with his own family in Sydney. He’s back in Australia for the 50th anniversary celebrations of the Opera House this month, and by way of a preview, he agrees to make a circumambulation of the building – a voyage round his father.

We take the clockwise route, setting off from the forecourt and down the western broadwalk. The day is partly cloudy, neither brilliant nor misty, and while the Opera House is magnificent in any weather, the light is harsh. We squint in the sun as the gleaming sails of the Concert Hall tower overhead.

Utzon marvels not only at his father’s building but at what its very existence has done for Sydney and for Australia. A living monument to the power of imagination, its halls are continually energised with music, drama and dance. As a landmark, it was an early example of urban regeneration, and reoriented the city to show its best face to the harbour. It has long been among Australia’s top tourist destinations.

Utzon says his father thought of the Opera House as like a “hearth” for the community, a gathering-place that would draw people around its flame. “One thing he was really happy about is that the people of Sydney and Australia have taken this building into their hearts,” he says. “As he said, a building is not worth anything unless people love it.”

Utzon walks slowly, having had a hip operation. Tourists amble past and shirtless joggers make their loop around Bennelong Point. We stand in front of the western foyer and the colonnade that, when it opened in 2006, was the first major structural change undertaken on Utzon’s building. Jorn Utzon after his long exile had agreed with his son and architect Richard Johnson to develop the Utzon Design Principles that would guide any future development at the Opera House. The completed works now include access tunnels and lifts to the theatres and foyers, the opening of the Utzon Room for chamber music and small receptions, and improvements to the Concert Hall and Joan Sutherland Theatre, whose interiors were designed not by Utzon but by Peter Hall.

“We developed a document that suggested a strategy if people in the future – in 50 years, 100 years – are going to do something,” Jan Utzon says. His father understood that people’s needs and expectations change with time.

“The Opera House was designed by 35, 45-year-old people who could climb Mt Everest. Now it’s with canes and walkers and things like that. They looked at it differently.”

A breeze picks up as we walk across the northern broadwalk and look down the chasm between the two main sets of the Opera House sails, called the “cleavage”.

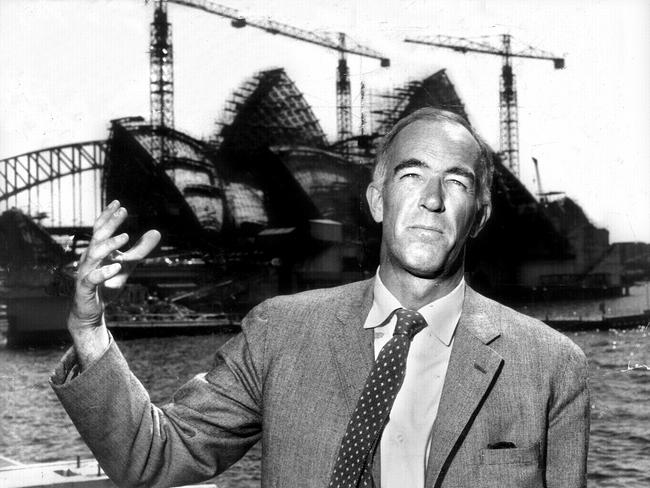

Utzon tells how the change of government in NSW in 1965 led to his father’s dismissal from the Opera House project. The Askin government couldn’t accept that such a complex building did not simply come out of a box.

“If you want to build apartment buildings like those over there,” he says, pointing across the water to Kirribilli, “you know pretty much how to do it. But here, you run into all sorts of problems, with sloping walls, interiors where you are not really certain – ‘How can I do this or that?’ All problems can be solved, and to my father, you solved them by making prototypes and models … The new government, they wanted to return the whole process of making the Opera House to something more like an apartment block.”

Raising the pressure, the government stopped paying Utzon’s fees and the architect and his family had no option but to close up shop and leave. His son says they thought they had come to Australia for good.

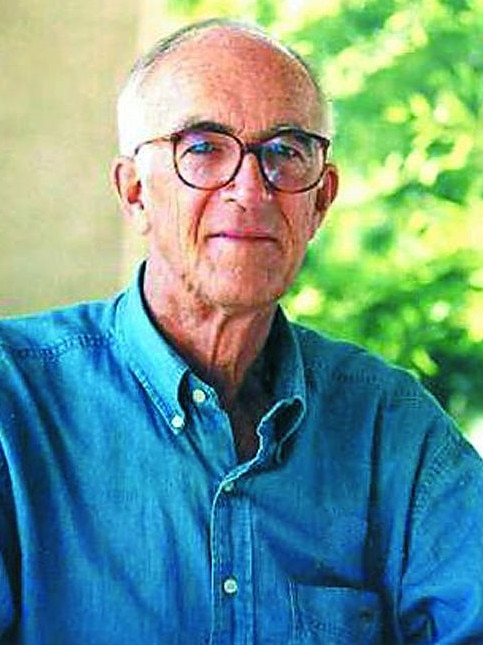

Utzon remained disappointed that he could not finish his masterpiece, especially the interiors, and never returned to Sydney.

“He didn’t want to come to Australia,” Utzon says. “Well, he did, actually, but he said, ‘If I come to Australia, I will be faced with all these questions – “How do you like what we’ve done?” And I can’t say it’s a lovely building because I really don’t like it.’ That was his hesitancy about coming here.”

The wind is strong as we head down the narrow eastern walkway and into the passage under the monumental steps. Utzon Sr had made designs for the Joan Sutherland Theatre, quite magnificent, that would replace its black-box interior with a scheme in festive gold leaf and red, and a proper orchestra pit. It would mean lowering the entire theatre by 4m and while it’s possible, Jan says, “it will take a lot of money”. For now, he’s been told, those plans are in the deep freeze.

As we head out of the tunnel and into the sunshine, Utzon says that thinking about his father, who died at age 90 in 2008, is unavoidable whenever he visits the Opera House.

“I feel he was rather clever, actually,” he says.

The Sydney Opera House’s 50th birthday festival continues through October. Jan Utzon, his sister Lin Utzon and Richard Johnson will discuss Jorn Utzon and his legacy at the Opera House on October 17.