Sydney Opera House designer Jorn Utzon’s city Aalborg celebrates his genius

The genesis of Jorn Utzon’s extraordinary Sydney Opera House, turning 50 this year, can be found in the architect’s former hometown.

It’s nigh-on a perfect day in Aalborg, the sky an unbroken blanket of blue and with barely a ripple on the surface of Limfjord, the waterway that bisects this elegant northern Danish city. The sails of a trio of yachts remain furled as they slowly circle, waiting for the top of the hour when the road and rail bridges raise their central spans to allow them through.

It’s nothing like the roiling waters and brooding skies a teenaged Aalborgian called Jorn Utzon would tackle on Sea Scout regattas. He would intuitively channel those forces of nature into a building on the other side of the world that polarised a city, excited and frightened politicians in equal measure and grew, imperfectly but strong, into the symbol of cultural Australia.

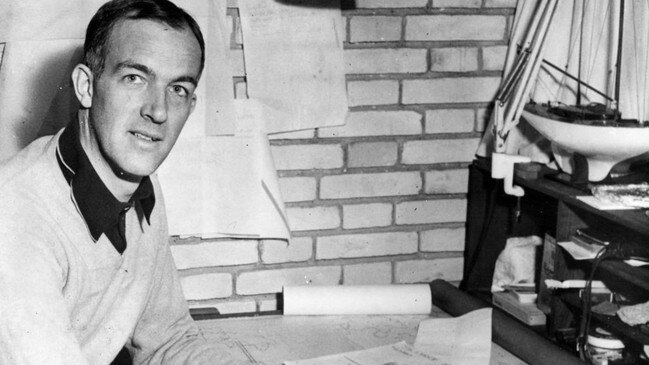

Utzon’s affinity with the sea underscores his oeuvre. Line Norskov Davenport, director of exhibitions at Aalborg’s Utzon Centre, which fronts the waters young Jorn would sail, says: “Boat building was always part of his creative universe, a place he could escape to. In all of his design sketches, you’ll find a small boat in it.”

Utzon would visit his naval-engineer father in Aalborg’s shipyard, lying beneath the boats to study how they were put together. Later, as a release from the Opera House’s confounding geometry, he’d dabble with boat design, and in 1961 he created the Tritail, a yacht with a three-pronged stern. Its model hangs in the centre. Davenport says Utzon found boat design beautiful but challenging, a condition that affected his efforts for Sydney. Still, she says, if he’d been given the time, “he would have worked everything out”. As the man himself said: “I like to be on the edge of the possible.”

READ MORE:Inside the new-look Sydney Opera House | Australia’s best World Heritage sites | Opera House from inside out | Hotel review: Intercontinental Sydney | Exploring the FIFA host cities and

But as boats are merely a human’s response to being in nature, so was Utzon’s architecture, and that’s at play on Bennelong Point. “I appreciate that it looks like sails. That’s him responding to his immediate surroundings,” says Davenport. “But the platform concept gives the feeling of walking up closer to the clouds, removing people from the urban jungle.”

Davenport, an architect who did her PhD on Utzon, says he saw the Opera House in three parts: the platform, the roof and the interior. They were separate but in harmony, and it’s the interior, particularly the vexed issue of the acoustics where, had Utzon stayed on, nature’s influence on the design would have borne fruit. “Acoustics came from how sound bounced off waves, not only reflected sound but how it spread out,” Davenport says. “That was the intuitive feeling he had.”

Among all the exhibits in the centre – designed by Utzon, it opened six months before his death in 2008 – the most poignant are prototypes for the Opera House interior, including one nicknamed the Geisha’s Wig. His resignation from the project in 1966, against the bullish force that was the then NSW minister for public works, Davis Hughes, meant they were not progressed.

“Sometimes it was seen as him being arrogant or mischievous,” Davenport says. “There was a rebellious aspect.”

Utzon’s striving for the best can be seen at every turn in the centre, one of several modern architectural contrasts to Aalborg’s otherwise centuries-old streetscape. Utzon travelled widely, and the building can be imagined like a series of desert tents. The centre holds all of his archive, and much will go on display in a permanent exhibition opening in October.

“It will be like a treasure chamber of pearls – prototypes, models, documents, reports,” Davenport says. “Some of them will reflect on what went wrong (in Sydney).”

A prized exhibit will be the Yellow Book, which captures the moment Utzon finally worked out the geometric principle of the roof. “Those drawings were extremely complicated; they’re virtually three-dimensional.”

While Utzon’s work is the centre’s backbone, it operates as a broader exposition of architecture and design. During my visit, one space holds an enormous origami-like structure, an imagining of an astronauts’ permanent house. There’s a robotics studio, an adjunct of Aalborg University in a discipline that would surely have intrigued Utzon. A children’s space, meanwhile, has a pit filled with white Lego pieces – just add imagination. Upstairs is an auditorium with a ceiling curving to a line of skylights, not dissimilar from designs we’ve viewed downstairs. Yes, confirms Davenport, they’ve had singers perform opera here.

Aalborg has a fine opera house of its own next door, plus a distinctive museum of modern art designed by an Utzon mentor, Finnish architect Alvar Aalto, stamping it as a very cultural city. In Kildeparken, behind the railway station, even the trees sing. Since 1987, music luminaries visiting Aalborg – from Placido Domingo and Van Morrison to Shakira and Kylie Minogue – have been invited to plant trees, and most have a pillar with a button that plays their music. Aalborg is also big on street art, and artists from all over the world have adorned about 80 buildings with murals. I spend a morning tracking them down via a not totally accurate phone app, before heading off in search of Aalborg’s origin story.

Lindholm Hoje, a low hill – Denmark has no other kind – was part of a Viking settlement from the 700s. The hill is a cemetery that archaeologists believe was covered by drifting sands 1000 years ago. Rediscovered last century, excavations have revealed about 800 graves. The burial ground is dotted with stones, some random but others in distinct patterns: ship-shaped for male graves, while women received circular or oval settings.

I’ve asked Davenport for restaurant suggestions and, an architect to her core, she recommends Struktur (fancy French) or Textur (Danish degustation). But tomorrow I’ve got a pre-7am train for the next stage of my Utzon odyssey, so I take a casual option. Sogaard, a restaurant/bakery/brewery/distillery on a square behind Aalborg’s main street, has a selection of smorrebrod, the feted Danish open sandwich, the most popular being stjerneskud (shooting star): panko-coated steamed plaice, marinated shrimps, salmon and caviar on toast with herb mayo and cucumber. To follow is flodeboller, a dome of chocolate-coated meringue on a nutty base.

Just north of Copenhagen are two significant Utzon touchpoints. In a way, Kronborg Castle, a fortress on a promontory at Helsingor, a town Utzon moved to in his late teens, is a Sydney Opera House prequel. It’s said that when presented with a similar situation at Bennelong Point the architect, referencing his experiences walking and sailing around the castle, realised his Sydney building, too, had to be beautiful from all sides.

The postscript to Utzon’s vision is found in a church in the Copenhagen suburb of Bagsvaerd, his first project after returning from Australia. Not the exterior which, with its concrete walls and metal roof, looks like an outback shed. It’s the interior that, according to Davenport, approaches Utzon’s vision for the Opera House, because here “he was able to do everything”. It’s dominated again by a split, curving ceiling, rising to an arch under which light enters through a line of semi-concealed windows. “It doesn’t look like clouds, but it’s closer,” Davenport says. “It’s a space our dreams can dwell.”

The church is open to the public most days, just not during services, and a line of young people waiting to enter this Sunday afternoon turns out to be architecture students from Kansas. For a university mob, they’re subdued, totally absorbed by this stunning space.

The Opera House saga was a story from my teens in Sydney, and I’ve often wondered how Denmark feels about Australia’s treatment of Utzon. Davenport is reassuring. “Most (Danes) feel a sense of pride that one of their countrymen went all that way (to Australia) to do that wonderful job,” she says. “The fact it’s been so well received around the world, it gives us a confidence.”

But the manner of his departure? “His willingness not to compromise? Honestly, I don’t know how I feel,” she says. “For me, the story is still becoming more and more nuanced, and I’ve studied this for years. I don’t put him on a pedestal. Very few people are perfect. He was just a man trying to do his best.”

MORE TO THE STORY

Throughout October, Sydney Opera House’s 50th birthday festival will be a smorgasbord of theatre, music, dance and art. Many events are free, including What is the City but the People (October 1), in which Sydneysiders can parade along a catwalk across the Opera House forecourt, backed by live artists. There’s an Open House Weekend (October 21-22), the venue’s first open days in eight years. And Utzon’s children Lin and Jan will discuss their father’s legacy, including his eventual re-engagement with the Opera House, in the Utzon Lecture (October 17).

A program of performances by Australian contemporary artists showcases the likes of Emma Donovan (October 20), Melbourne trio Camp Cope (October 13), and drumming troupe Taikoz (pictured) with local Indian dance company Lingalayam in Chi Udaka (October 18-21).

Imported big guns include chamber orchestra Academy of St Martin in the Fields (October 7-9) plus Bark of Millions (October 18-20), a world premiere rock opera from American performance artist Taylor Mac. Sadler’s Wells Theatre will present Message In a Bottle (October 25-29), a display of hip-hop and contemporary dance set to the music of Sting.

IN THE KNOW

The Utzon Centre is open daily except Mondays.

Aalborg is the largest city in northern Denmark, about five hours by train from Copenhagen.

The ubiquitous Eurail pass is now a user-friendly phone app, allowing travellers to search timetables, adjust connections and store train options in the trip planner. Single country, regional and global European passes are available.

Jeremy Bourke travelled at his own expense with the assistance of Rail Europe.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout