‘A phenomenal process’: inside the new-look Sydney Opera House

After a two-year makeover costing $300 million, Australia’s iconic cathedral of the arts – and one of the glories of world architecture – is almost ready for its close-up.

To reach the “crown” of the Sydney Opera House involves a journey a bit like Quasimodo’s in The Hunchback of Notre Dame. You enter through a nondescript door – the location is secret for security reasons – and begin a steep climb up a set of spiral steps. Then it’s along a narrow passage, and another, and up a second spiral stair. And it is a bit like climbing into the bell tower of some magnificent cathedral. There’s a feeling of the space closing in the higher you go, into the uppermost parts of Jørn Utzon’s magnificent sails. Finally, you land on a platform above the roof of the Concert Hall. Directly beneath is the “crown” – the hall’s distinctive pattern of concentric circles of ceiling lights. Up here, hidden from public view, is a complex array of winches and cables that are used to raise and lower lights and sound equipment over the Concert Hall stage.

The stage machinery, painted in bright blue enamel, is all brand new. Viennese engineering firm Waagner-Biro made the original stage machinery for the Opera House when it opened in 1973, and has produced the new winches to replace the old. All of the machinery and new structural supports – about 300 tonnes of it – has been brought up to the roof piece by piece, via a tiny funicular lift between the Concert Hall and the outer concrete shells.

“These are not your average winches,” says Lou Rosicky, project director for the Concert Hall renewal project. “As part of the Concert Hall works, we have installed both the biggest winches that we’ve got anywhere in the Opera House, and the smallest winches as well.”

All of the winches, and just about everything else in the Opera House, have been designed especially for this extraordinary, if idiosyncratic, building. “Nothing we do here is off the shelf,” Rosicky says. “Everything is custom made. It’s been a phenomenal process.”

The stage machinery is just one dimension, although a crucial one, of a makeover of the Concert Hall that is nearing completion. In the foyer areas, visitors will soon be able to walk through a tunnel that links the southern entry of the Concert Hall to the Northern Foyer and its magnificent harbour views. A new lift – inserted into Utzon’s building with exquisite engineering – will take concert-goers from podium level to their seats in the dress circle.

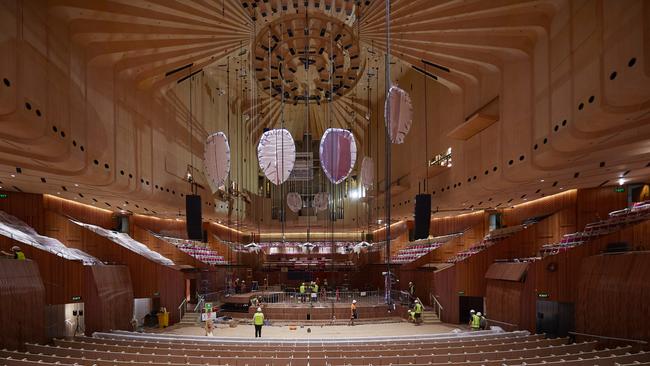

There are changes inside the hall, too. Much has been done to improve the imperfect quality of sound in the auditorium that John Malkovich, the American actor, once described as “hideous”. The most noticeable new feature is the large, petal-shaped sound reflectors above the stage, painted the same vibrant magenta as the colour of the seat fabrics.

When the work in the Concert Hall is completed in July, it will be the culmination of a 10-year program of upgrades across the performing arts complex, worth a combined $300m. The “decade of renewal” in the lead-up to the Opera House’s 50th anniversary next year – including work already completed on the Joan Sutherland Theatre – has been the driving mission of Louise Herron, who arrived as chief executive in 2012.

“It’s sort of surprising to me that we said, ‘We need to renew this Opera House for future generations of artists, audiences and visitors’, and 10 years later, it’s happened,” Herron says. “And you go through day by day, you slog on, and you engage this person and deal with this issue – and then it’s done. That was 10 years.”

To understand why improvements to the Concert Hall have been desirable, if not necessary, it helps to recall some of the troubled story of the Opera House and of the Concert Hall in particular.

Utzon was working to a brief that the main hall of his Opera House would be suitable for orchestral concerts as well as grand opera. After his break with the Opera House project in 1966, Peter Hall took on the task of finishing the building, including the interiors and the auditoriums. When the state government in 1967 finally settled a dispute over the use of the main hall – that it would be for orchestral concerts in the main, and that opera and ballet would be presented in the smaller venue now known as the Joan Sutherland Theatre – Hall needed to find a solution that would be practical, musically appropriate and beautiful.

And “Hall’s hall” is indeed a wonder to look at. The focal point is the Grand Organ, whose silver pipes stand in ranks behind the concert podium. The auditorium was finished entirely in timber: ruddy-toned brush box, and creamy white birch for the ceiling, where waves of plywood radiate from the crown. The seating was arranged in continental style, without a central aisle, and with series of boxes along the sides.

Early listeners were enthusiastic about the new hall but its limitations became apparent. As a venue for classical music and other unamplified performances, the auditorium is too large. Sound is lost in the 22m void under the crown, meaning that the musicians in an orchestra – 100 or more in a large Romantic symphony, for example – cannot hear each other properly. And front to back, the hall is too long for people to experience the music as it should be heard.

Before the Sydney Symphony Orchestra gave its first performances in the Concert Hall in September 1973 – in the inaugural concert, Charles Mackerras conducted the Immolation Scene from the Ring cycle, with Swedish soprano Birgit Nilsson – acrylic rings or “doughnuts” were fitted above the stage as sound reflectors. By the late 1990s, Dutch conductor Edo de Waart, the SSO’s chief conductor at the time, decried the hall’s poor sound quality, saying the acrylic reflectors were no more useful than toilet seats. He threatened to take the orchestra elsewhere unless the acoustic problems were fixed.

Other conductors were not so colourful in their language but continued to point out the hall’s shortcomings. Simon Rattle, visiting with the Berlin Philharmonic, said the sound as experienced on stage was confusing, because it “seems to come from all sides”. David Robertson, the SSO’s chief conductor from 2014-19, lamented the lack of harmonic richness, the individual character of the instruments being lost.

Previous attempts have been made to address the acoustic problems, including “risers” or small platforms of various height for the musicians, replacing the “sawtooth” wall panels that were part of Hall’s original design, and hanging black drapes in the hall as acoustic dampeners. The Concert Hall upgrades that are nearing completion have incorporated all of these modifications, but in a sophisticated and aesthetically pleasing way. Adjustable risers that match the footprint of an orchestra’s main instrumental sections have been incorporated in a fully automated stage that can be raised or lowered as required. Acoustic banners can be lowered from the ceiling crown like roman blinds. And timber panels can be lowered from the side walls, providing additional acoustic reflection. The idea is that the hall can be easily adjusted for different performance “modes”, whether orchestral music, amplified contemporary music, or talks – making the hall more enjoyable for a wider range of artists and audiences.

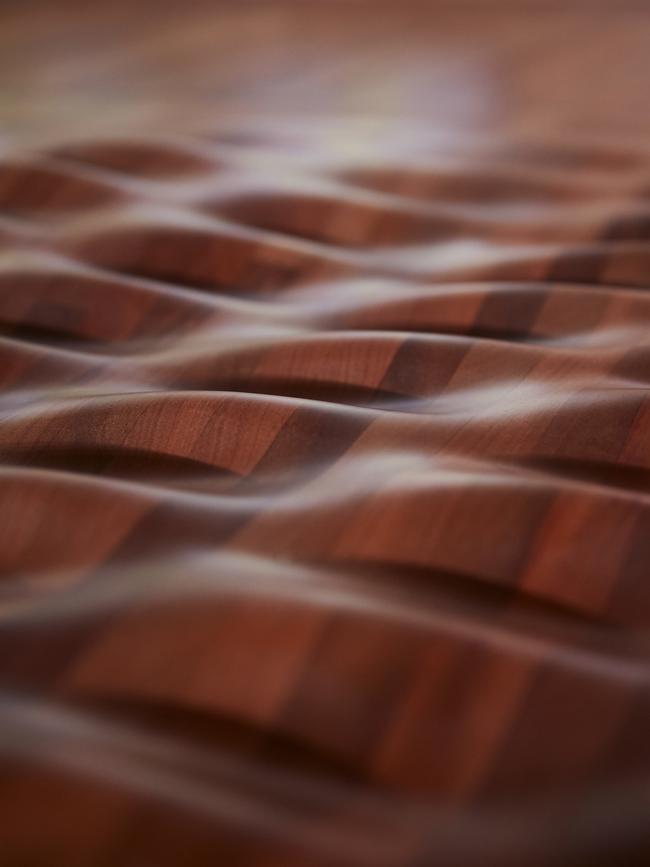

One of the most startling changes, because of its overall effect, is the replacement of the brush box wall panels with acoustic diffusion panels, constructed from the same timber. The panels are carved with smooth contours, creating a ripple-like effect around the Concert Hall’s perimeter. Andrew Hayne, project architect on the Concert Hall upgrades, says the panels are intended to help enrich the experience of orchestral sound – the contour pattern was based on a computer image of sound waves.

“That’s the pattern you see on the walls,” he says. “It ticks the acoustic box, but it also created these beautiful surfaces – incredibly tactile and wonderful to look at.”

The acoustic modifications were first made as prototypes and given a road-test by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra. “The feedback from the orchestra was incredibly positive,” Hayne says. “They were saying things like, ‘It’s the first time I have been able to hear myself in this room. It’s the first time I have been able to hear other sections of the orchestra.’ The team is very confident that the results will be there on the night.”

Hayne, a principal with ARM Architects, has overseen the daunting work of some not insignificant changes to Utzon’s structure. Concrete beams in the northern foyer have been cut to allow the installation of the lift. And a tunnel has been cut through the grand staircase on the Concert Hall’s eastern side. It is lined with sculpted brass panels and royal purple carpet – colours and forms that echo other design elements of the Concert Hall.

Hayne says the tunnel and the lift at the far end will greatly improve access for people, particularly the elderly and the less mobile. He says Utzon’s original plans for the Opera House had indicated a passage at this location. “If you imagine the staircase without the tunnel, it’s like climbing a mountain,” he says. “I have been to plenty of concerts here and watched the elderly struggle up those stairs. The fact that Utzon had a concept for a passageway meant that there was something we could latch onto as an idea.”

The “decade of renewal” at the Opera House has completed an overhaul of Australia’s most iconic building. The Joan Sutherland Theatre, home to Opera Australia and the Australian Ballet, in 2017 underwent similar upgrades, including new stage machinery and the installation of a lift and discreet access tunnel. The harbourside Yallamundi Rooms were opened for function hire, and the Centre for Creative Learning opened earlier this year with a program of performances and educational experiences for young people. No less significantly, cars and trucks have been removed from the Opera House forecourt. “One of the most difficult things was telling people they can’t park there,” Herron says, in her harbour-view office. “It’s not a car park, it’s an opera house.”

The construction works at the World Heritage-listed building have been done in consultation with heritage experts as well as various design and conservation committees, and with reference to a document called the Utzon Design Principles. “We have so many layers of approval to go through, and all of those things have been approved, and everything has been done with such love and meticulous care to ensure that it completely complies,” Herron says. “We are technically completely compliant and we have been through every process.”

Together with earlier modifications at the Opera House – including a chamber-music venue called the Utzon Room, and the opening of the Western Foyers that lead to the Drama Theatre, Playhouse and Studio – more of the Opera House is now accessible to more people. Offices within the building have been moved to open up areas that the public can now enjoy. Pre-pandemic, the Opera House and Bennelong Point would welcome more than 10 million visitors a year.

Now that the building works are almost complete, the next task is to start bringing people back – arts-lovers, international tourists, and the Covid-wary. It’s Herron’s belief that the Opera House is, and should be, for all. In coming months plans will be revealed about the celebrations to mark the 50th anniversary of the Sydney Opera House next year.

“We are still working on making people feel not only that the outside belongs to everyone, but that the inside belongs to everyone,” she says. “We need to show people and make sure that in every way that we operate, and the way we welcome people to the site, the way we reach out through our digital programming – that everything we do [lets people say] ‘This is my place, this belongs to me.’”

The completion date for the Concert Hall was pushed back several months, after delays due to the pandemic and problems with the supply of components – including freight from Europe that was held up when the cargo ship Ever Given ran aground in the Suez Canal. Now, teams are working around the clock to have the hall ready for its official opening. Sanders are stripping back the timber floors. Acoustic banners are being attached to their cables. Carpets are being vacuumed and glass polished.

When the hall opens in July, it will be with a homecoming gala concert by the Sydney Symphony Orchestra under its new chief conductor, Simone Young. The program? A new commission by composer William Barton, and Mahler’s Symphony No 2, called the Resurrection. Appropriately enough, as the Concert Hall awakes from more than two years of silence, looking and sounding like new.