Intrepid artist painted the colony

George French Angas was in a sense predestined to be the first artist of South Australia.

This exhibition, which I mentioned in my roundup of summer exhibitions a few weeks ago, was meant to start in August last year, finally opened in November, and will run for another three weeks at the National Library. It deals with an important but hitherto little-known figure in the history of Australian art, and sheds a unique light both on the earliest history of South Australia and New Zealand and on contact with the Indigenous peoples in the first years of European settlement in those regions.

We might wonder why an exhibition of such art-historical significance is being shown in a library rather than a gallery or museum; the reason for this is that George French Angas intended his work primarily for publication in book form, not for hanging as fine art. And indeed although I recommend that readers see this exhibition if they can, I would even more strongly urge them to buy Philip Jones’s outstanding book, which is far more than a catalogue.

It is a handsome volume, impeccably scholarly and yet eminently readable; Angas’s pictures are beautifully reproduced and can be better enjoyed in this form than on the wall, where it can be wearisome to look closely at so many small and detailed images in the space of a couple of hours. Above all, though, the book helps us to see far more in these pictures than we could by ourselves, offering a fascinating insight into the character and life of Angas and the circumstances of the foundation and early years of Adelaide.

Angas’s detailed ethnological and cultural documentation of the South Australian Aborigines and of the New Zealand Maori is no doubt what drew the author to this project. Philip Jones is a senior researcher at the South Australian Museum and a specialist on Aboriginal culture, and incidentally the author of an excellent chapter on Aboriginal art in the new Wiley Companion to Australian Art which I edited and which was published late in 2021.

Angas (1822-86) was born into a wealthy family, but in no sense an aristocratic one. His grandfather had established the family fortune in maritime trade, and his father George Fife Angas had considerably expanded the business, extending into banking and other investments. But they were not part of the old establishment, for reasons that were then of great importance but must seem arcane to many contemporary readers.

Catholics had been disqualified, since the Test Act (1673) from Oxford, Cambridge, the civil service and military or political office. But Protestants who did not recognise the supremacy of the Church of England suffered similar disabilities, although freedom of worship was allowed under the Toleration Act (1689); these laws were repealed for Dissenters in 1828 and Catholics in 1829. Dissenters were thus excluded from the traditional cursus honorum of the upper classes, which could take a talented boy to Eton and then King’s College at Cambridge, followed by appointments in the public service, a commission in the army, or a seat in Parliament.

Dissenters, often from modest backgrounds and without the benefits of a patrician education, held the strong conviction that success in life came from hard work, self-discipline and temperance. They could be humourless and puritanical, but they were also idealistic and humanitarian and believed in justice and integrity. This new middle class would gain increasing influence in the 19th century and give the Victorian period its characteristic tone.

These were also the people who founded the new colony of South Australia; George Fife Angas was one of the most important leaders of the new enterprise, which was designed to establish a city of free, honest and decent people, quite different from the rabble that had initially populated Sydney half a century earlier. An important aspect of their vision of the new community was that the Indigenous population should be well-treated and legally protected, even though the expansion of the colony inevitably led to dispossession.

George Fife Angas invested considerable sums of money in the new enterprise, and although these investments were ultimately profitable – he purchased most of the Barossa Valley, for example – he also spent so much on philanthropic causes both in Britain and in South Australia that at certain points even his finances seem to have been severely stretched.

This then was the family into which George French Angas was born, so he was in a sense predestined to be the first artist of South Australia. As Jones points out, conversations around the family dinner table, from his earliest childhood, must have been full of the plans for every aspect of the new colony, both before and after its inauguration in 1836.

As a boy, George showed remarkable talent, particularly for natural history illustration, and grew up determined to be an artist, rather than to take up what should have been his place in the family business. His father was certainly disappointed by this, although fortunately he had another son who was extremely competent and energetic in attending to the family affairs. And he seems to have tolerated and even to a degree encouraged George’s interest in art because it could help to promote the new enterprise in South Australia.

As the author shows, there was a burgeoning public interest in the new worlds being opened up by colonisation in the early 19th century, and in the native peoples of other continents. Colonial expansion, the rise of a new literate but semi-educated middle class, and new technologies of printing and image reproduction – lithography and then chromolithography – all combined to produce a new market for illustrated travel publications.

Angas must have conceived the plan for a book about South Australia – a completely fresh subject to which he could have intimate access – several years before he set off for the new colony. To practise and develop the requisite skills, he first published a short account of a visit to the Isle of Wight (1840); a more ambitious tour resulted in A Ramble in Malta and Sicily (1842).

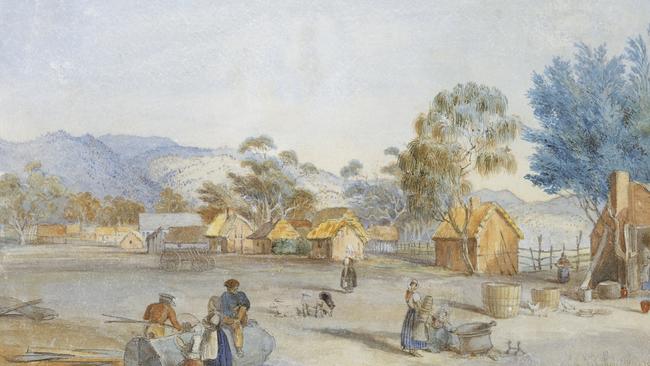

In 1843, he sailed to Australia, arriving in Adelaide at the very end of the year. His brother was already living there, and his property is illustrated in Terraworta on the Gawler River. The illustration Mr Evans’s Higher Sheep Station is of another property belonging to his brother-in-law; Bethany, a village of German settlers, depicts a village of German Lutheran tenant farmers whose passage to Australia had been paid by George’s father; and the work Opening of the Free Chapel at Angaston commemorates the inauguration of the chapel again funded by G.F. Angas. Some of these images are original watercolours by Angas, others are hand-coloured lithographs; throughout the exhibition and the book the differences between the original watercolour – when it has survived – and the published version are important and instructive: sometimes tone or colour can vary subtly but significantly, and sometimes more substantial changes have been made between the original and the published version.

These eyewitness views of the new settlement were what George’s father particularly wanted from him, and the corresponding lithographs are from George Fife Angas’s promotional publication Description of the Barossa Range and its neighbourhood, which came out in 1849, two years after his son’s South Australia Illustrated (1847). The new colony was developing so fast that one of the 1844 watercolours of a shepherd and his flock overlooking open pastureland had to be updated for publication in 1849 with the addition of a copper mine and several new residences.

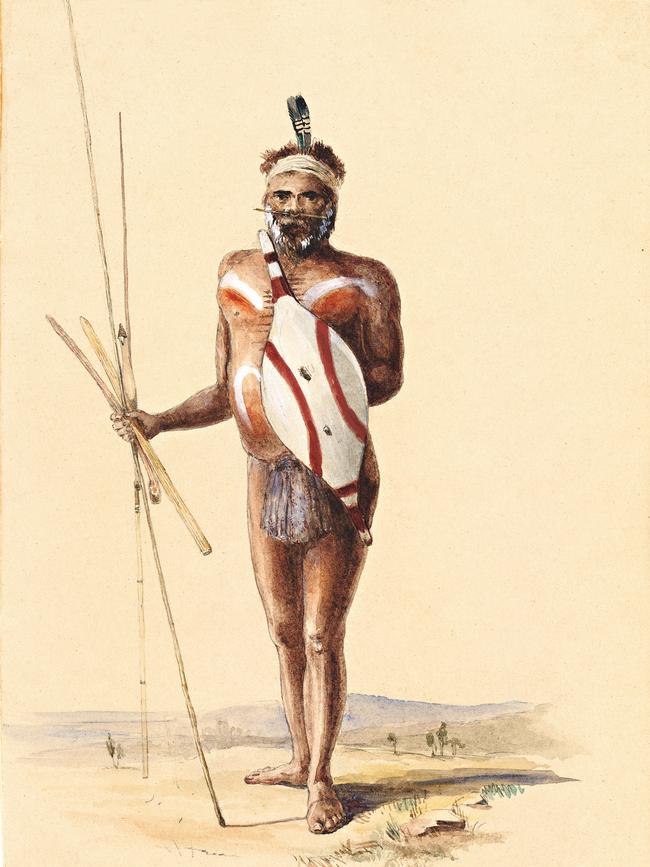

Meanwhile, Angas was particularly interested in representing the native peoples, and in this he was assisted by several people in Adelaide including a young schoolmaster, William Cawthorne, whose diaries are an invaluable source for this period of his career, and especially by the young, energetic and idealistic governor, George Grey, who was himself an ethnologist who had made a study of local Aboriginal languages.

Angas was invited to join Grey on several official journeys he made to the hinterland of the colony and made sensitive and sympathetic portraits of many individuals, taking care to include their names and their tribal affiliation. It is interesting to consider this sensitivity in an artist who was perhaps most skilful as a natural history painter, especially as we sometimes hear the complaint that early colonial artists depict Indigenous peoples in the same way they might depict natural history specimens.

But even from this point of view Angas’s human sensitivity should not surprise us if we reflect that every category of natural history has been approached in the way appropriate to its subject: seashells, for example – and Angas was an expert conchologist – are organically formed but inert; flowers are living and growing; insects, birds, reptiles and mammals, are living and moving. Humans are not only living and moving but conscious, sentient, responsive to the eye that is scrutinising them.

If the humanity of these watercolours is surprising, it is perhaps rather from another point of view: there was clearly a strain of narcissism in the artist’s character, and one could expect this to be antithetical to sensitivity. There are perhaps two reasons why it does not prove an obstacle: one is that we all find it easier to escape from the bounds of the ego with people who are not like ourselves; the other is that even narcissists can transcend the ego when absorbed in inherently selfless processes like artistic or scholarly work.

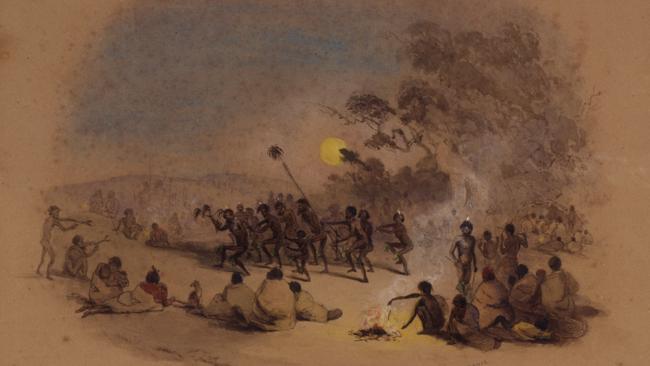

It was not only on these expeditions, however, that Angas had the opportunity to draw Aboriginal subjects. Some of the local Aborigines in Adelaide had discovered they could make good money as models. More importantly, tribes from around the colony would come to Adelaide at the full moon for the government distribution of rations; this incidentally had the effect of breaking down traditional tribal boundaries and prohibitions against venturing on to the land of other tribes. But it also became the occasion for tribal celebrations and corroborees which, as elsewhere in the early colonial days, the settlers could also watch.

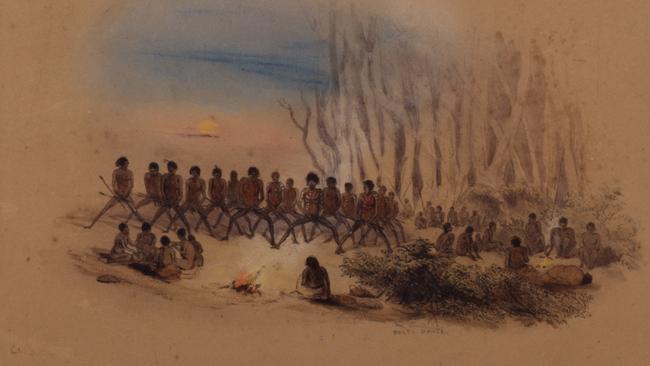

Angas returned from one of his expeditions with Grey just in time to witness two ceremonial dances performed under the full moon. One was executed by a local group, the other by a tribe from further north. We still have the two remarkable watercolours he produced, which together became plate 15 in South Australia Illustrated.

Almost more moving is the little pencil sketch he made of the “Kuri dance”, which he must have drawn in the dark or with a small oil lamp; we can feel the artist’s attention to the composition of the scene, and particularly his effort to capture the characteristic movement of the dancers. Unlike Grey, Angas was not a linguist and had not received that kind of education; but to a mind trained to capture the distinctive morphologies of living things, patterns of choreographed movement could be as significant as the forms of syntax to a philologist.

Illustrating the Antipodes: George French Angas, National Library of Australia, until January 30

Philip Jones, Illustrating the Antipodes: George French Angas in Australia and New Zealand 1844-1845, published by National Library of Australia