Hard cops and mean streets made TV crime series history

Homicide: Life on the Street still looks innovative and only slightly dated – and is as dramatically satisfying as it was first time around.

“I always liked television – I always thought television could do certain things that features can’t do,” Barry Levinson says. “I got David Simon’s book, Homicide: A Year on the Killing Streets, and I thought, ‘This is really terrific, but I don’t know how you’re going to cut this down to a two-hour movie’.”

Instead, the director, who had already won an Oscar for Rain Man and had directed the respected Good Morning, Vietnam, decided it could make a TV series.

“It’ll be about a homicide squad and how they deal with death regularly. It’s not an action story where we’re chasing the bad guys. There’s a murder and you’ve got to try to deal with it, and it also follows their personal lives.”

And so, Homicide: Life on the Street was born in January 1993. It ran for seven seasons on NBC, a free-to-air broadcasting network, until May in 1999, succeeded by Homicide: The Movie, the series finale.

Set in Baltimore, it became one of the most influential TV shows in history, putting race at the centre of the police procedural, and highlighting just how fraught racial politics can be within police departments, including those that are racially diverse.

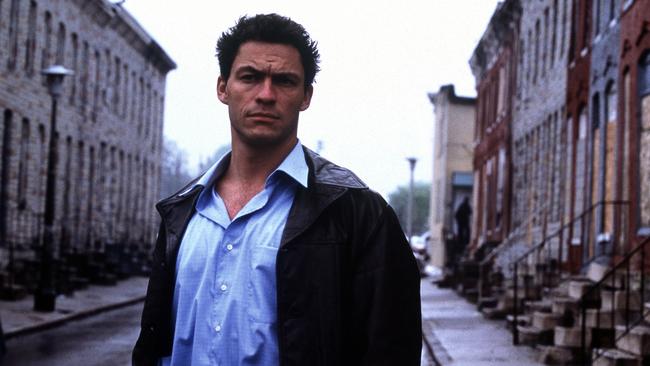

It defied convention, often leaving murder cases unsolved, and was distinguished by its diverse cast. This was rare in that period, and the series set new aesthetic standards for commercial TV as well as for traditional genre-driven cop shows. It was also shot and edited in a way that for TV was experimental and immersive.

Its ensemble-playing style, literary dialogue, grim moral ambiguity, and complex, many-threaded storytelling, influenced by the successful Hill Street Blues, with its microcosm of a beleaguered police world, created new standards for commercial TV.

Critics loved it, even if viewers, apart from a core of fanatic devotees, were slow to accept its experimental style. (One influential TV magazine once called it, “The Best Show You’re Not Watching”.)

The series won four Emmy Awards and many other honours. It was nearly dropped after its first season, but was saved by a guest appearance by Robin Williams, and was given a second season. Homicide also drafted Simon to TV, his long list of shows that followed including The Corner, Generation Kill, Treme, The Deuce, and of course The Wire.

It also attracted many other serious artists, mostly in the form of guest stars like Williams, Melissa Leo, Jake Gyllenhaal, Cris Rock, Vincent D’Onofrio, Steve Buscemi, Alfre Woodard, James Earl Jones, and proud Baltimorean John Waters, who once described Homicide as “the grittiest, best-acted, coolest-looking show on TV”. (The first episode even features the great Australian actor, Wendy Hughes.)

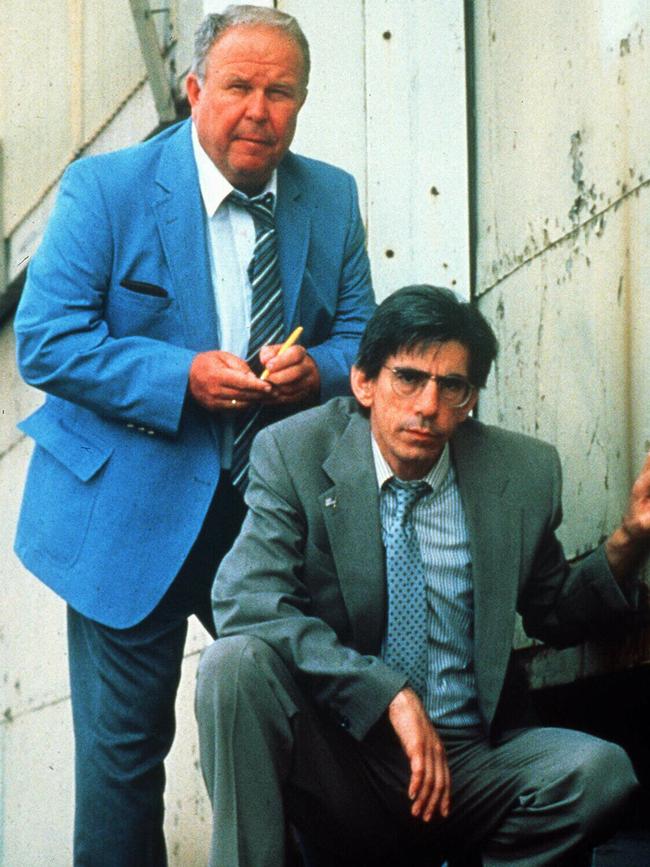

The show also made instant stars of Andre Braugher, who played the combustible Detective Pembleton, and Richard Belzer who created the doleful Sergeant John Munch, who was sarcastic and comical.

It has now arrived in the streaming era, released last year after years of delays due to the legal challenges of securing music rights. (Unfortunately, most of the original songs in the wonderfully eclectic soundtrack have been replaced.)

Homicide’s welcome return is part of the way the streaming revolution has resurfaced many beloved titles from throughout TV history. SBS recently gained the local permissions and has begun screening the show to a largely new audience.

Homicide still looks innovative and only slightly dated and is as dramatically satisfying as it was first time around.

Mind you, it was never easy dealing with NBC. Simon joined the show midway as a writer and producer and in his introduction to Rafael Alvarez’s account of the making of The Wire, he wrote of the continual dismay of the network executives.

They would ask the same questions every time they read a first draft. “Where are the victories?” and “Where are the life-affirming moments?” Nevermind, he wrote, that it was called Homicide and that “it was being filmed in a city struggling with entrenched poverty, rampant addiction, and generations of industrialisation.”

The series was initially based on the characters in Simon’s book, the writer then an investigative reporter at the Baltimore Sun, who took a year off to follow a homicide unit.

“They used the book as a jumping-off point,” Simon says in an interview with the Television Academy. “It was real-life in places. They changed the characters, and they also created fictional ones. Andre Braugher’s Detective Pembleton and Richard Belzer’s character had much more going on in their brains than actual detectives, a lot of whom were, ‘Get the job done, f..k this, f..k that, solve the case, go home, drink a beer’.”

Levinson, who still talks of how lucky he was with the show, managed to get a deal with NBC to do six episodes “of something in which there would be no network involvement in content or casting”.

He went off and did it, bringing into the project Tom Fontana, one of the writers responsible for the critically acclaimed NBC series St. Elsewhere, for which he wrote 97 episodes. There he had helped pioneer the story structure that weaves several narrative threads together in one hour. Levinson also engaged a young writer called Paul Attanasio to write the original script.

(The series title was originally the same as Simon’s, but NBC changed it so that viewers would not believe it was limited to a single year; the network also believed the use of the term “life” would be more reaffirming than the term “killing streets.”)

“It was a non-glamorous show in all respects,” Levinson says in the Academy interview. “We wanted it to have the feel of the struggle of being detectives dealing with community issues and how they behave.”

As he says, crime shows traditionally were strongly plot-driven, mysteries solved at the end of each episode, and the audience comforted by the way reason and morality always triumphed over wrongdoing.

Homicide was very different.

The first episode, Gone for Goode, directed by Levinson, is a classic, at times moving and at others very funny, opening and closing with detectives standing over a dead body in the middle of the night. Attanasio brilliantly establishes both the grim, grimy location but also managed to establish nine different characters in the ensemble.

One of the cops at the start says, in reply to something his colleague mutters, “Life is a mystery; just accept it,” setting the elegiac style of dialogue that distinguishes the series.

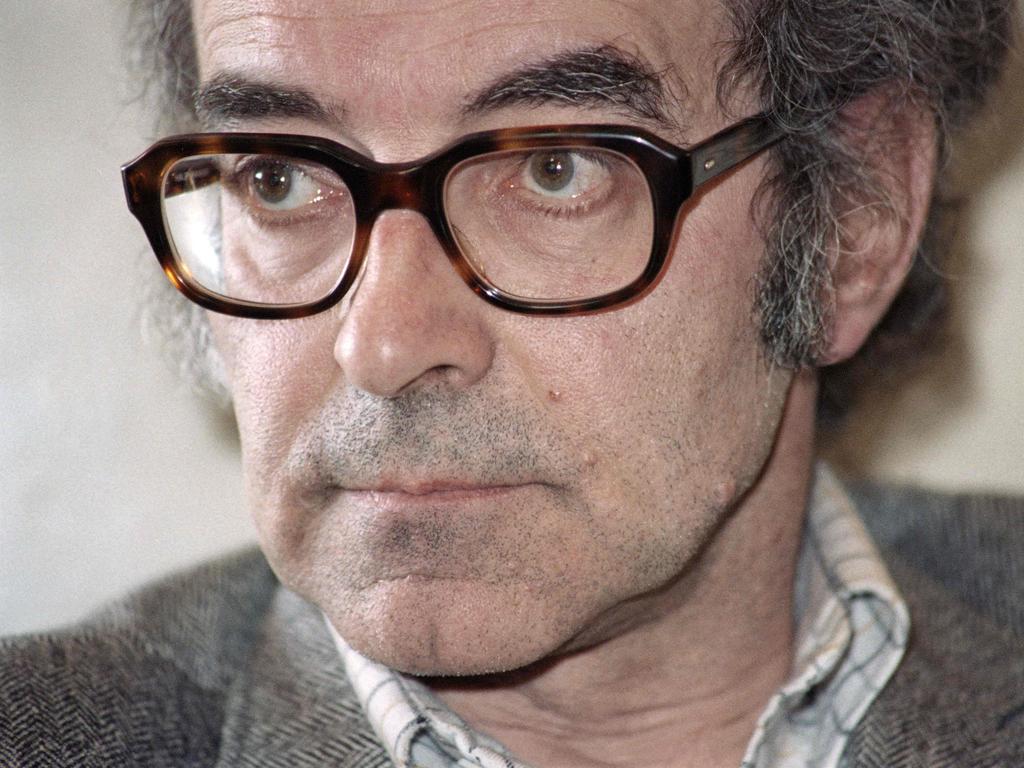

Levinson sets the cinematic tone, shooting it with a handheld Super 16mm camera, with often confronting jump-cuts influenced by the directors of the French New Wave, Jean-Luc Godard especially. (A jump cut is an editing technique portraying a skip in time, heightening the energy in a scene or the emotional intensity.)

“We’d shoot the scene one way, the other way, from down low, from up high – whatever would give it an energy,” says Fontana, the operator often sitting on a chair or a box, camera on his shoulder. “Every actor had to be on their game because you never knew when the cameras would be on you.”

New boy Tim Bayliss (Kyle Secour) leads us into the squalid squad room, all but ignored by the other cops who are involved in various cases that play out through the episode. We ride with them as they banter and investigate. A cold case is cleared as a murder and two other murders are opened and cleared on the same day. “It’s like mowing the lawn; you gotta mow it again,” one of the cops mutters. Another says, “It’s really getting to me; I wake in the night and look at my body and think it’s a chalk outline.”

We’re introduced to The Board, a central motif, a large display with each detective’s name, followed by the case number and last names of the murder victims in the cases they investigate. “You look up there, you know exactly where you stand,” Yaphet Kotto’s Italian African-American squad leader, Al Giardello, tells Bayliss, “About how many things in life can you say that?”

Then there’s The Box, the mean-looking interrogation room where detectives help criminals “reflect on the errors of their ways”. In a famous speech, hot-shot Pembleton, known for closing cases in The Box, tells Bayliss, “What you will be privileged to witness is not an interrogation, but an act of salesmanship – as silver-tongued and thieving as ever moved used cars, Florida swampland or Bibles – but what I am selling is a long prison term. To a client who has no genuine use for the product”.

Asked about the show 25 years later, Fontana told radio station NPR, “I’ve been trying to figure it out,” he said. “It’s unfortunate that the stories we told are still relevant. But it might engage a younger audience, because they can say, ‘Hey, prejudice, and misogyny and inequality are still part of day-to-day life’.”

Homicide: Life on the Street streaming on SBS On Demand.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout