The point is an old one, but perhaps more relevant than ever in a world where instantaneous communication has made many things seem urgent that are not even truly important. We constantly put such tasks ahead of the important ones, and yet within days or weeks most of those jobs we had thought so urgent are revealed as entirely trivial, and we still haven’t dealt with the important matters we put off. On a larger scale, this is the same pattern of narrow thinking that plagues business as well as government. Real success, growth and prosperity, equity and social development come from thinking beyond the short-term cycles of fiscal years and elections. But we are trapped in a mentality of deadlines and urgency: reports have to be written, forms filled, documents submitted, mostly never seen again.

Even budgetary decisions about what is and is not an economically viable investment depend largely on the time frame assumed, as well as the scope of consequences and side-effects, positive and negative, that are to be taken into account. As we know, a given solution may be prima facie more expensive than another, but in reality more economical if we include the cost of the environmental effects of each.

In the same way, the cost of infrastructure investment has to be offset against all the expected benefits, including indirect ones. The capital cost of building a very-fast-train network in Australia, for example, will never be recouped in ticket sales, but would more than pay for itself if it slowed urban sprawl and allowed regional centres to flourish, fostering healthier and more dynamic communities than those that stagnate on the fringes of our main cities.

The perspective of a few months or years is dwarfed by that of history, in which lifetimes and whole generations are subsumed into longer movements and currents: “ … the iniquity of oblivion blindly scattereth her poppy, and deals with the memory of men without distinction to merit of perpetuity,” as the great prose stylist Sir Thomas Browne wrote in Urn Burial (1658), citing the fact we recall the name of the arsonist who burned the temple of Diana at Ephesus but scarcely remember that of its architect. But historical time itself is eclipsed by the far greater duration of prehistory and both are swallowed up in the incomprehensible depth of geological and cosmological time. Until the advances of natural history and geology in the later 18th and the 19th centuries, many believed – and fundamentalist Christians apparently still do – that the world was created about 6000 years ago. Indeed Browne’s slightly older contemporary, Bishop James Ussher, set the beginning of Creation on October 22 or 23, 4004BC, probably around 6pm.

This date, which fundamentalists believe to be based on the word of God – or as one such website puts it, an eyewitness account – was actually arrived at by adding up the lifespans of the figures named in the Old Testament until that chronicle intersects with events for which we have secure historical evidence. The supposed date is so recent that religious authorities were disturbed by the progress of Egyptology, two centuries ago, which clearly indicated a much earlier date for the beginnings of civilisation in the region.

Interestingly, Greek historians already knew Egypt was extremely ancient, and Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BC, could see that it would have taken many thousands of years for silt carried by the Nile to form the Nile Delta – for which reason he famously called Egypt the gift of the Nile.

The progress of life sciences and also of geology in the late 18th century made it very clear that the Earth was considerably older than the churchmen had thought. Buffon, the giant of French natural history and also a great prose stylist who inspired Edward Gibbon, came to the conclusion that the Earth had once been a molten mass, and conducted experiments with a cannon ball to test its probable rate of cooling.

Extrapolating from the mass of the cannon ball to that of Earth, he came up with an immensely long cooling period before life could have arisen, but in the end compromised and published 75,000 years as the Earth’s age. This was of course still unacceptable to the church and he was forced to publish a retraction; but by 1778, in the last years of the ancien regime, this seems to have been little more than a formality.

Since Buffon’s time, science has pushed back the chronology of the world dramatically. It is now hypothesised that the universe as we know it began with the Big Bang almost 14 billion years ago, although the really disturbing thing about that theory is not how long ago the event is supposed to have taken place, but that a finite duration can be ascribed to the universe at all because, just as in theories of creation, this begs the question of what there was before the beginning. So curiously, the latest scientific theories do little to solve problems long posed by philosophy, or indeed even theology. Either the universe is infinite in both time and space; that is, duration and extent, or it is finite. In either case we are left with an equally impossible question about what is or was before or beyond it, not to mention how something came out of nothing.

By now we seem to be looking into the Total Perspective Vortex imagined by Douglas Adams in The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (1978). But Marina Castillo Deball’s work is concerned not so much with the ultimate philosophical problems raised by the age of the universe, as with the unimaginably long duration of time involved in the evolution of life and living forms.

The exhibition begins with fossils, those enigmatic remains of once-living if barely sentient creatures whose remains have formed some of the kinds of stone, like limestone, of which the Earth itself is formed. Then we are taken even further back to the pre-organic ages of geological time, and large diagrams on the wall remind us of the vast extents of duration involved in these unimaginably remote times.

The main part of the exhibition, at the end, is a poetically conceived labyrinth of diaphanous curtains, printed with images of outback landscapes in the Ediacara Hills, part of the Flinders Ranges, where important fossil work is being undertaken. The visitor walks through and between these veils, as though in compressed recreation of the desert spaces. Clear panels allow one to see through them at certain points to the next set of images.

The rather dreamlike nature of this work is in striking contrast to the verbose and largely irrelevant text of the press release that announced it, a typical product of the automatic writing of contemporary art: “Her art responds to a seemingly total state of globalisation, in which Western traditions attempt to assimilate all others. The philosophical questions she contemplates are deeply rooted not only in the manifestation of her own indigenous Mexican identity, but also in the increasing importance of cultural specificity around the globe.”

The reference to “indigenous” Mexican identity, used as a token of credibility, is disingenuous since Mexicans have for 100 years identified with mestizo background.

And as for themes of globalisation, it is hard to see what relevance they have to periods before the appearance of life on Earth, let alone the hegemony of the West. Globalisation had a rather different meaning when our world was just taking shape.

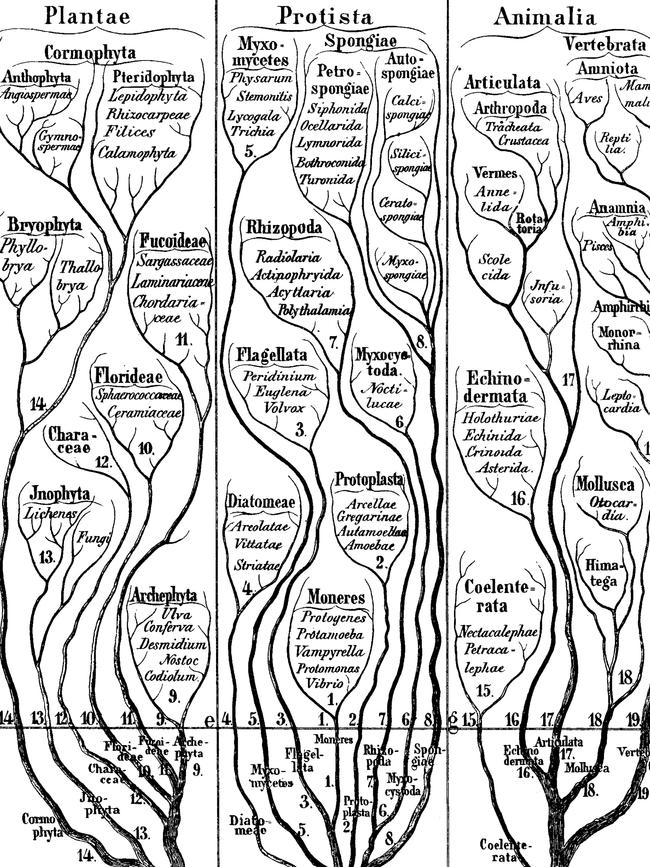

One of the most interesting elements in the exhibition, and pertaining to this very question, is a diagram originally published in 1866 and blown up on a wall. It is by Ernst Haeckel, and titled in Latin Radix communis organismorum: the common root of organisms.

Haeckel (1834-1919) is best known for his remarkable illustrations of botanical forms, including microscopic ones, and The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel was published earlier this year by Taschen. He was a great supporter of Darwinism, discovered and named thousands of new species and coined a number of words we use every day, including ecology and stem cell. And speaking of new words, it is only fair to recall that Sir Thomas Browne also gave us the words prototype and archetype.

Haeckel also has an Australian connection: in 1866 he took as his assistant on an expedition to the Canary Islands a brilliant young naturalist, Nicholas Miklouho-Maclay (1846-88), who later came to Sydney and worked with the eminent Australian naturalist, Alexander Macleay, whose Elizabeth Bay House still stands, a rare survivor of the great colonial houses of this part of Sydney. Haeckel’s diagram is a Tree of Life, and the most striking thing about it, especially to non-specialists, is that he divides living things into three kingdoms: Animalia, Plantae and Protista, which includes many things that fall into neither of the first two categories, such as sponges and other simple marine organisms. The tree invites us to think back to a period at which three different kinds of life were first emerging, destined to evolve in different directions, but at first no doubt so primitive as to be almost indistinguishable.

One characteristic of this exhibition that may have occurred to the reader is that it suggests ideas and in that sense is thought-provoking, but does not actually do much to shape or direct our thoughts. Undoubtedly one function of art is simply to make space for thought; to take us away from the world of noise and preoccupation and utilitarian concerns, and invite us to muse on, or simply dwell with, ideas of broader interest. But more satisfactory art, in any medium, shapes and directs our consciousness more decisively, leads us to see things, rather than leaving us to drift in our own associations of ideas.

This exhibition is an occasion for thought but, as an aesthetic experience, remains rather bland, passive and undefined.

-

Marina Castillo Deball: Replaying Life’s Tape

Monash University Museum of Art. Until December 7

The perspective of time changes the appearance of most things, though perhaps not of everything in human experience. Much of what we worry about in the course of a day at work, all of those large or small things that cause us what is today referred to as stress, soon become forgotten and even incomprehensible. Even the people who once annoyed or tormented us gradually fade into indifference and forgetting.