Hype abounds: NGV’s Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat exhibition

A fierce and ongoing promotional campaign has over-estimated the significance of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s art.

New York in the 1980s, as late modernism turned into postmodernism — or as the art market grew more and more cynical and hysterical — was in the last phase of its post-war hegemony. American art had first come to international prominence with the new abstraction of the 1940s to the 1960s, which had made New York the capital of contemporary art. Then followed pop and a long twilight under the presiding genius of Andy Warhol, who died in 1987.

In Warhol’s last years, two younger artists came into his orbit, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. Both had begun with graffiti but were adopted by an art market voracious for novelty. They were not destined to outlive their patron for long, however. Basquiat was a junkie and died of a heroin overdose in 1988 at the age of 27. Haring fell victim to the new plague of AIDS and died in 1990.

Almost at once, each of them was canonised by the art establishment, less for the quality of their art than for who they were and what they represented: Haring became a martyr of the gay community and Basquiat was eagerly embraced as a rare example of a black artist, all the better for being a troubled and tragic figure.

Since then, the promotional campaign to sustain the assertion of their importance has been unrelenting, as will be clear to anyone who glances at the number of glossy publications — all recent ones — in the NGV bookshop. Books like this cost a lot of money, and that money is not the expression of wonder at the genius of the artists or the love of their pictures.

It is an investment in maintaining the reputations of vast bodies of largely repetitious work that is valued at an extraordinarily high price by the market. In 2017, a picture by Basquiat sold for over $US110m, a record price for any American artist. That is more than $A157m, a huge sum of money and a good example of the principle I mentioned recently; that it is a mark of distinction for the super-rich to pay more than anyone else, and especially to pay more for less.

But no one wants to lose this kind of money. Even if the purchase is an example of conspicuous consumption, that act would lose its social prestige if the picture were revealed to be worthless. It is thus imperative for the collectors, dealers and museums that hold these assets that they continue to be valued highly, and they will spend relentlessly to keep the bubble inflated.

The NGV exhibition is another expression of this massive promotional exercise: the show is enormous, expensively installed with a notable emphasis on the personality cult of the two individuals, including their association with Warhol, and accompanied by a massive catalogue whose very size and weight are an assurance of the importance of its contents. Surely these artists must be significant?

What lies behind the hype? Haring was a graffiti artist with an undoubted talent for whimsical and sometimes disturbing figures always painted in the same schematic way, so that his works have an immediately identifiable brand quality, like the work of a designer.

One of the most interesting things in the exhibition is the short film clip of Haring scurrying down into the New York subway and drawing in chalk on an empty space painted black and destined for an advertising poster, before being caught and arrested by a police officer — an unfortunate guy doing his job who is cast, as so often in this kind of situation, as the stooge of authority.

Of course the film clip is self-conscious and promotional, but one can see that the interest of these chalk figures is precisely that they introduce enigmatic and seemingly symbolic images into the lives of commuters otherwise surrounded only by commercial advertising posters — a note of questioning and wonder into a world of routine and constraint.

Haring’s technique of drawing is adapted to these circumstances, and to the need to work quickly and decisively: it is highly formulaic and pattern-based, so that he can draw whole figures in a single outline and a shape can seem illegible until the contour returns to complete the matching side of the image. His forms are like prefabricated modules which can be assembled in different ways depending on the space and the time available.

Another film clip is among the rare high points of the exhibition, and shows the remarkable Bill T. Jones dancing a solo piece in which every movement is like an act of discovery, always with a clear sense of purpose and measure and yet open like an improvisation. In the background, Haring paints an increasingly complex and threatening mural decoration.

Haring’s work is inherently more interesting in such live settings, and the formulaic and abbreviated language developed for real-time performance is less satisfactory when repeated in cold blood for exhibition in art galleries.

But graffiti art became popular in the declining years of New York as the market scrambled for any last vestiges of authenticity. Of course, whatever authenticity graffiti possessed evaporated in its commodification as art market product. Haring himself was not unaware of this and is quoted in the exhibition, rather pathetically, as saying that business is evil.

All very well when business has paid you a very good price for your soul.

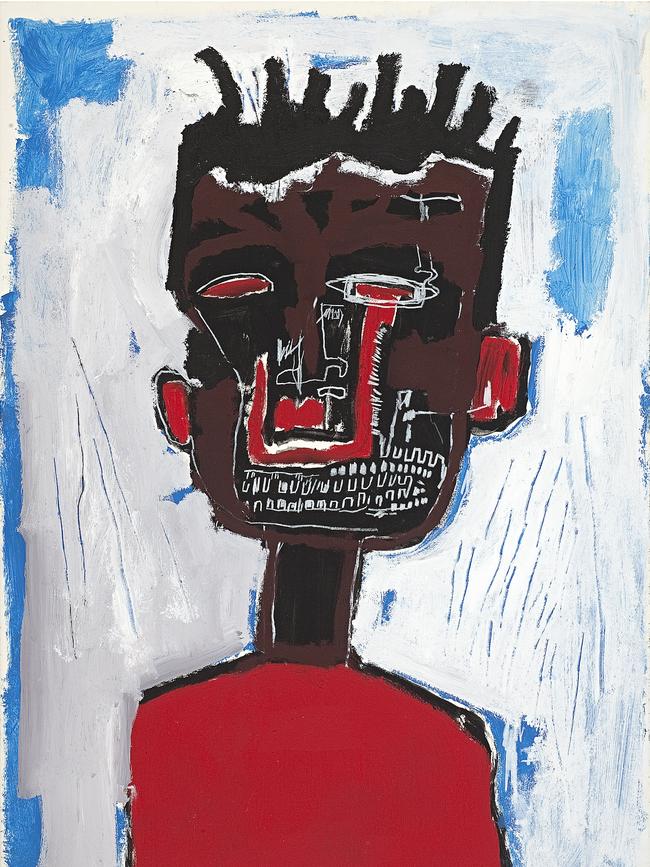

The case of Basquiat is even more extreme. If you walk through the NGV exhibition without preconceptions and without pausing to read the breathless adulation of his genius, you will probably see at once that Basquiat was an artist of negligible ability, who worked fast and carelessly to pay for his drug habit and repeated himself endlessly and unimaginatively.

To give some idea of Basquiat’s overproduction, he made some 200 paintings in 1982 alone, considered by the market to have been his best year. Altogether there are more than 2000 works. His dying of a drug overdose was clearly the only thing that prevented Basquiat swamping the market with a quantity of facile work that would eventually have caused its commercial value to implode.

In order for Basquiat’s reputation to be sustained, it is essential to present him as original, visionary, complex and socially engaged. So throughout the exhibition, visitors will encounter labels making surprisingly implausible claims for the work.

Thus one informs us he was given a copy of Gray’s Anatomy as a child and his close study of this textbook informs his subsequent work; the picture in question, however, has a doodled impression of inner organs that owes no obvious debt to any anatomical textbook.

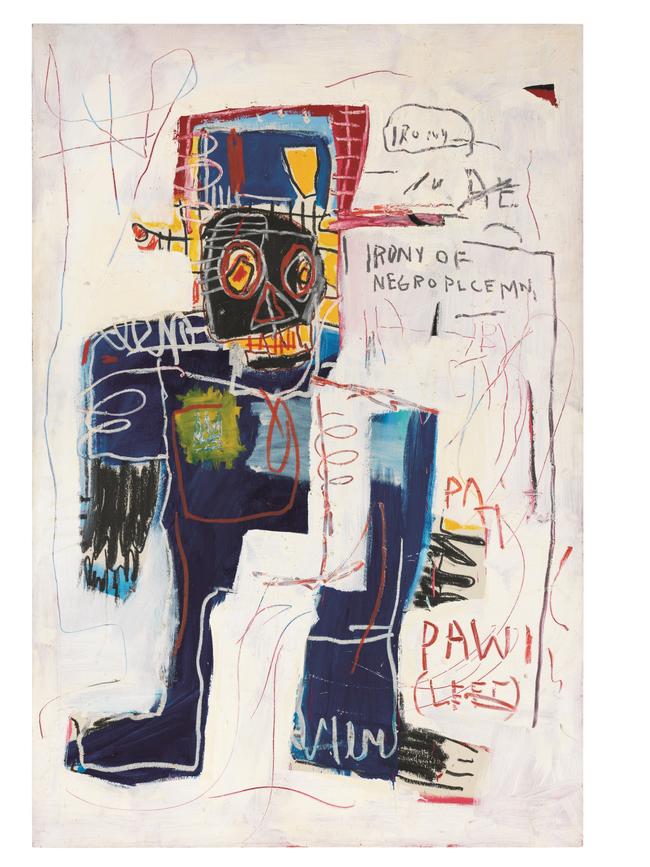

Again, and predictably, his work is said to be deeply political and concerned with questions of slavery and the history of black people. Thus one of his works is inscribed with the profound words: “Irony of negro policeman.”

Other incoherent references abound, and he bought into the fallacy that the ancient Egyptians were black. Wishful thinking went a long way in the political climate of the time.

Basquiat’s style started in graffiti, and its transition to the art gallery and the art market is perhaps even less successful than Haring’s. Unlike Haring’s cool formulaic approach, Basquiat’s is based on frenzied scribbling. To these images he adds a variety of inscriptions, including a stylised crown that is a personal logo, and more or less random words, some of ostensibly political or social significance and others drawn from the flotsam and jetsam of the consumer world.

A mannerism imported from graffiti is to write words in incomplete form, or to write and then cross out all or parts of the words.

This is interpreted by his promoters as significant but is in reality just a gimmick that is endlessly repeated and becomes part of the look of the work.

And what are these images about, in the end? Basquiat’s supporters are in a bit of a quandary, because they want to interpret them as powerful statements of rage and resistance but also, as one of the labels asserts, as images of strong, confident black men.

In reality, and leaving aside the many things that people might want them to mean and seek to project on to them, these images embody pain and confusion and desperation, the unsurprising state of mind of a drug addict and of an artist who may have had some inkling that his commercial success was ultimately hollow.

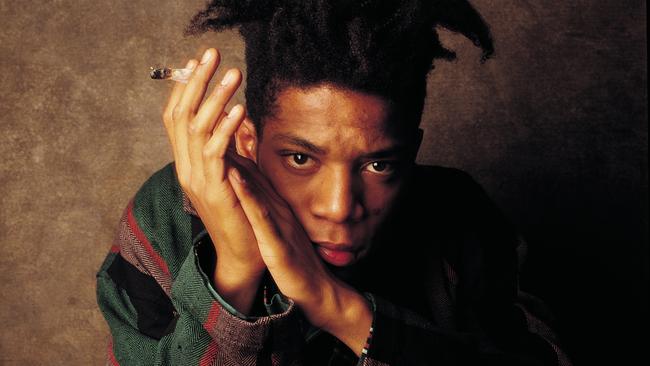

What Basquiat had going for him was that he was young, pretty and black. The market was excited by a neo-primitive expressionism that made questions of actual ability irrelevant, while everyone wanted this young black protege of Warhol to be a “superstar” — a term apparently coined by Warhol.

When he died, the art establishment fell over itself in the rush to sing the praises of their dead Rimbaud. Almost the only voice of sanity was our own Robert Hughes, who published his assessment in The New Republic in November 1988, under the unforgettable title “Requiem for a featherweight”.

The essay was later reproduced in Hughes’s collection, Nothing if Not Critical (1992), still the indispensable companion to the intellectually and financially corrupt art world of the 1980s.

Hughes’s essay can easily be found online if readers do not have a copy of the book, and it should certainly be read before visiting the exhibition as a prophylactic to the torrent of disingenuous commentary to which the visitor is subjected. Here is an abridged version of one paragraph: “Basquiat’s career appealed to a cluster of toxic vulgarities. First, to the racist idea of the black as naif … and to the idea of the black artist as ‘instinctual’, outside ‘mainstream’ culture, and therefore not to be judged by it. Second, to a fetish about the infallible freshness of youth, blooming amid the discos of the Downtown Scene. Third, to an obsession with novelty – the husk of what used to be called the avant-garde. Fourth, to the slide of art criticism into promotion, and of art into fashion. Fifth, to the art-investment mania which abolished the time for reflection on a ‘hot’ artist’s actual merits; never were critics and collectors more scared of missing the bus than in the early 80s. And sixth, to the audience’s goggling appetite for self-destructive talent. All this gunk rolled into a sticky ball around Basquiat’s tiny talent and produced a reputation.”

This was the beginning, in the 1980s and 90s, of the contemporary art business we have inherited today, in which promotion always trumps critical perspective, and in which the ultimate values are money and fashion. People are still buying Basquiat and others like him, and exhibitions like this will continue to be mounted to support the reputations of featherweights.

Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat: Crossing Lines

National Gallery of Victoria, until April 13

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout