Hugo Race’s Road Series stories travel a road of rock and soul

Birthday Party guitarist Hugo Race shows rare self-awareness as his life and art descend into chaos.

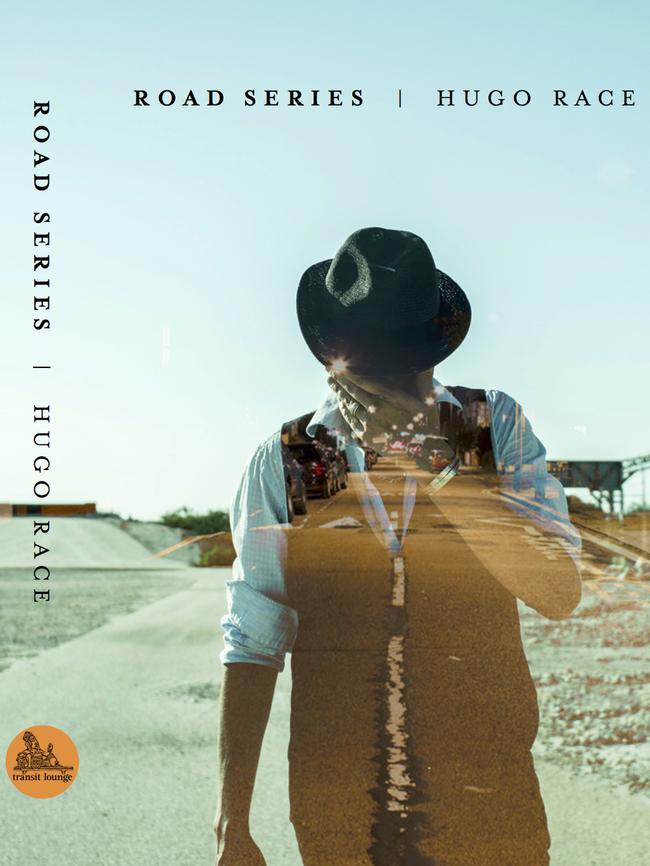

Road Series, by Hugo Race (Transit Lounge, 368pp, $29.95)

It has taken me a while to understand this. But in Road Series rock musician and travel memoirist Hugo Race has thrown up nothing less than his struggle to return home from the dream of who he wanted to be.

A founding guitarist with Nick Cave’s notorious backing group the Bad Seeds, Race previously emerged on the Melbourne scene as the 18-year-old front man for Plays With Marionettes. Marked as crown prince in waiting behind Cave (what a curse), Race then formed the Wreckery, outlaw junkie blues in a Melbourne style that could have seen them fall into the role of saloon band for a TV western such as Deadwood.

Since then Race’s star has shone dimly on the horizon. He was lost in eastern Europe somewhere, he was writing a novel, he was big in Italy in a romantic duo known as Sepiatone, then suddenly he was touring here, alone, and gone before you knew it. Now and again a song would come through: too gritty, downbeat or smoky to be a hit but never an iconic bullseye either; just something strong enough to make you think, oh yeah, that guy had something.

Road Series shows he still does. In spades. Told in tight and often tense focus, this superb nonfiction book comprises 14 stories. It opens with Race’s experiences around the Crystal Ballroom arts scene in Melbourne in 1981 — “the energy like a cage full of parakeets” — before shifting through what was then West Berlin, the Czech Republic, Yugoslavia, Sicily, Brazil and Mali. Sometimes these movements can feel less like a journey than a spiral.

Once Race has you inside that experience his road tales stir up their own existential dust clouds within you. Men, in particular, will empathise with the restless impulses as Race matures and negotiates, with mixed success, how to hold on to his family and continue in a career he is halfway between committed and addicted too. In a key scene, a musician with similar problems makes a backstage appeal to Race: “You know, I just want to be a good man. How hard can that be?”

This is no conventional rock diary, though it is saturated in references to Race’s love of music from the Delta blues and Johnny Cash to punk, psychedelic and electronic rock. A first sighting of the Birthday Party at the Crystal ballroom is typically vivid as they “take the stage with a wall of noise — fuzz distortion, the sonic aroma of pure electricity eating itself … with this kind of violent firepower the stage resembles a wrestling ring or Grand Guignol circus, the singer standing in the middle as ringmaster, blowing smoke out both nostrils”.

Elsewhere, while driving, Race hears on his radio “the symphonic devastation of Arvo Part’s Cantus beaming down … funereal tubular bells and shimmering glissandos from deep in the Baltic soul, all minor keys, crescendos, choirs, polyphony. Music as brutal as this recognises the infinity and sacredness of grief.”

Unlike most self-absorbed rock biographies, the loose-weave coherence of Road Series is distinguished by Race’s awareness of himself and a world in flux. We also witness an artist’s technological adaptations as we see Race move from recording demos on cassette tape to emailing collaborators across the planet. Context is everywhere; if anything, history feels like it is crushing Race into its shadows.

An early visit to his brother suggests the dangers to come as they sit around “reading journalists like James Fenton and Ryszard Kapuscinski, frontline reporters covering secret wars in current conflict zones, dirty deals, black ops. It’s inspiring, the idea of travelling this global horror show and writing it into truth.” On those terms Road Series can hold its head up as true rock ’n’ roll reportage. Race was one of the first musicians to venture deep into eastern Europe after the Berlin Wall fell. No front-page headlines for him, just the messy reality: low-budget, even dangerous. As he heads with his wife and baby daughters towards a concert in Prague, a nervous energy takes hold on “a two-lane blacktop with intermittent cat’s-eye reflectors. The only signs I understand are Stop and Exit, everything else is hieroglyphs. Occasionally red and blue chemical smokestacks break the horizon, discharging mystery cocktails into a mass of bruised cloud. Here, all the birds are black.”

Later, Race admits “a deep sense of uselessness haunts me after performing the music”. He ends up indulging in vodka and pills. “I’m not sure who anybody is — their faces are strange but friendly and my own face feels glued on. By now I’ve forgotten who I really am, enough to be easily led astray, like another version of myself that I don’t really like.”

Here Race locks on to the chaotic sadness of post-revolutionary Czechoslovakia. His writing style is often compressed and edgy like this, reflecting, perhaps, the influence of Berlin and an expressionist aura that can marry the contradictions of personal corruption and genuine political struggle to resist. References to AIDS, to Ronald Reagan and everyone making jokes about Chernobyl — while “nobody drinks the water here unfiltered” — are sveltely touched on. Just when his stories begin to feel repetitively dark in style and content, the ground shifts to Mali and Brazil. The latter heightens Race’s supernatural inclinations; while Mali, for all its poverty and struggles with Islamic extremism, inspires and energises.

On the flight to Mali he reads Cormac McCarthy’s novel The Road. A woman beside him mistakes it for Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. Race’s thoughts surge: “The vast gulf between Jack Kerouc’s beat (sic) generation and the apocalyptic doom of McCarthy illustrates the distance Western culture has travelled in the last half century; beat generation expectations of the groove-filled search for kicks and endless highs has morphed into a race against time with planetary self-destruction and a general reckoning with the collective heart of darkness — maybe that’s why I’m 10,000m over the Mauritanian Sahara heading south en route to the city of mystery, par excellence, Timbuktu.”

Maybe. Maybe Race is also trying to save himself. It makes for a hell of a life journey, as well as a call to think more widely about how one makes art in a savage world. You close this book understanding Race may not be a perfect man but he is certainly a good one.

Mark Mordue is an author and critic.